Search in dictionary

Inspection

望诊 〔望診〕 wàng zhěn

One of the four examinations. In inspection, the practitioner observes the patient’s general physical appearance, paying special attention to any part relevant to the presenting condition. Apart from observing the patient’s spirit, overall appearance, and complexion, the practitioner also carefully examines the tongue, which can provide invaluable information about the state of the bowels and viscera.

Contents

- Inspecting the Spirit

- Inspecting the Skin and Flesh

- Inspecting Body and Bearing

- Inspecting the Complexion

- Infant’s Finger Examination

- Tongue Examination

-

Inspecting the Head, Face, and Neck - Inspecting the Chest, Abdomen, Back, and Lumbus

- Inspecting the Limbs

- Inspecting the Two Yīn

- Inspecting Eliminated Matter

Inspecting the Spirit

In the context of diagnosis, spirit

refers to the degree of vitality of the patient. Thus, the term is here used in a sense different from that of the spirit

as stored by the heart. The spirit as vitality is reflected in the patient’s facial expression, complexion, bearing, and general state of consciousness. It also takes account of the quality of voice, enunciation, and verbal expression, which, of course, strictly belong to the listening and smelling examination.

Spiritedness, Spiritlessness, and False Spiritedness

It is said, If the patient is spirited, he is fundamentally healthy; if he is spiritless, he is doomed.

Conditions of the spirit fall into three fundamental categories: spiritedness, spiritlessness, and false spiritedness.

Spiritedness (有神 yǒu shén)

Patients who have bright eyes, normal bearing, clear speech and who respond coherently to inquiry, are said to be spirited, indicating that right qì is undamaged and the complaint is relatively minor. Although certain aspects of the patient’s health may be seriously affected, swift improvement may be expected.

Spiritlessness (无神 wú shén)

Spiritlessness can occur in both vacuity and repletion patterns and manifests in slightly different ways:

Vacuity of right qì: Spiritlessness attributable to vacuity of right qì manifests in listlessness of essence-spirit, dark facial complexion, torpid (i.e., dull and lifeless) expression, slow reactions, incoherent response to inquiry, dull eyes, faint low voice and halting speech, faint breathing or forceless panting, severe emaciation, and abnormal bearing and difficult movement. In severe cases, there can be clouded spirit,

which is partial or total loss of consciousness.

Exuberant evil: Spiritlessness occurs with other disturbances of the spirit in several evil repletion patterns:

- yáng brightness (yáng míng) (yáng míng) disease patterns in cold damage manifesting in clouded spirit, delirious speech, agitation,

picking at bedclothes

(循衣摸床 xún yī mō chuáng, unconscious, fumbling movements of the hands, calledcarphologia

in biomedicine) or

(撮空理线 cuō kōng lǐ xiàn), where a comatose patient reaches into the air, sometimes spreading the fingers and sometimes drawing them together, as if pulling at strings.groping in the air and pulling invisible strings - Phlegm-fire harassing the heart manifesting in mania and agitation (or manic agitation), and in serious cases delirious raving, accompanied by vigorous heat effusion, rough breathing, and phlegm rale in the throat.

- Heat entering the pericardium manifesting in clouded spirit, delirious speech, and manic agitation together with vigorous heat effusion.

- Extreme heat engendering wind in infants and children manifesting vigorous heat effusion, clenched jaw, and convulsions. This is it is called

acute fright wind,

which is the result of extreme heat engendering wind (this may be observed in influenza or encephalitis B). - Liver yáng transforming into wind stirring manifesting sudden clouding collapse (sudden clouding of the spirit that makes the patient fall to the ground), which leaves the patient with hemiplegia and impaired mental faculties is seen in wind stroke (stroke, apoplexy).

- Phlegm clouding the heart spirit manifesting in spiritlessness, sudden clouding collapse, foaming at the mouth, and occasional squealing like a pig or goat constitutes an epileptic seizure. This occurs when wind carries phlegm upward to obstruct the clear orifices (wind-phlegm). It is observed in epilepsy patients.

False Spiritedness (假神 jiǎ shén)

False spiritedness usually occurs in enduring or severe illness and extremely severe cases of essence-spirit debilitation. If, suddenly, in a condition characterized by taciturnity, a low voice, halting speech, and an extremely dull or dark facial complexion, the patient becomes strangely garrulous and his cheeks unusually red as if smeared with oil paint, this new condition is said to be one of false spiritedness. This is sometimes described in Chinese as the last radiance of the setting sun

(回光反照 huí guāng fǎn zhào), or in English as the

or a dying flash.

Such conditions are critical and should not be mistaken for improvement. False spiritedness implies a superficial improvement in certain aspects of the patient’s mental state that does not accord with other aspects of the condition. It is a sign that the patient’s condition will soon deteriorate dramatically and therefore demands special attention.

Spirit Abnormalities

Note that some abnormalities of the spirit overlap with spiritlessness discussed above.

talking to self,

jumping over walls and climbing onto roofs,

casting off one’s clothes and running around,

violent and destructive behavior,

nonsensical talk,

and chiding and cursing or laughing and weeping, regardless of who is present.

Deranged spirit (神乱 shén luàn): Severe spirit abnormalities.

Agitation (躁 zào, 躁動不安 zào dòng bù ān), manic agitation (狂躁 kuáng zào), manic derangement (狂乱 kuáng luàn): Agitation

means pronounced fidgetiness (i.e., constant changes in posture and nervous movements). Manic agitation

and manic derangement

mean agitation with signs of deranged spirit. It manifests in frantic movements, reduced sleep, profuse dreaming, nonsensical talk, and beating and cursing people regardless of who is present. It occurs in mania disease and is usually attributable to qì depression transforming into fire that boils liquid into phlegm and then combines with the phlegm to harass the heart spirit.

Clouded spirit (神昏 shén hūn): Partial or total loss of consciousness occurring in heart disease or disease affecting the heart in the following conditions:

- when insufficiency of yáng qì disperses the heart spirit;

- when fire harasses the heart spirit; or

- when phlegm obstructs the orifices of the heart.

Clouded spirit can occur in vacuity and repletion patterns: Vacuity patterns include desertion patterns and fulminant desertion of heart yáng. Repletion patterns include heat entering the pericardium, bowel heat patterns, heat toxin attacking the heart, summerheat patterns, phlegm-fire clouding the spirit, extreme heat engendering wind, wind-phlegm internal block patterns (as in wind stroke). Mild forms of clouded spirit are described in such terms as torpid essence-spirit

(精神迟钝 jīng shén chí dùn) or unclear spirit mind

(神志不清 shén zhì bù qīng).

Clouding collapse (昏倒 hūn dǎo), also called sudden clouding collapse

(猝然昏倒 cù rán hūn dǎo): Sudden clouding collapse

means sudden clouding of the spirit that makes the patient fall to the ground.

- When this is accompanied by drooling and foaming at the mouth, upward-staring eyes, squealing sounds, and convulsions that disappear when the patient regains consciousness, this is an epileptic seizure, which is explained as liver wind carrying phlegm counterflow to obstruct the clear orifices.

- If the patient loses consciousness without the above-mentioned signs and regains consciousness but is left with hemiplegia (paralysis of one side of the body), the disease is wind stroke (i.e., stroke in the sense of cerebrovascular accident in biomedicine).

Clouding reversal (昏厥 hūn jué) Sudden loss of consciousness attributable to major disturbance in the movement of qì.

Tetanic reversal (痉厥 jìng jué): Sudden loss of consciousness occurring in tetanic disease (diseases marked by severe spasm).

Listlessness of essence-spirit (精神萎靡 jīng shén wěi mí): A severe lack of mental energy occurring in severe vacuity patterns such as yáng collapse or yīn collapse. It is a sign of spiritlessness.

Indifference of spirit-affect (神情淡漠 shén qíng dàn mó): Also called indifferent facial expression

(表情淡漠 biǎo qíng dàn mó). Lack of interest in the world, as visible in an indifferent facial expression and bearing. It is seen in yáng collapse, feeble-mindedness, and in mania and withdrawal.

Affect-mind depression (情志优郁 shén zhì yōu yù): A depressed emotional and mental state marked by moodiness, depressed anger (irritability, grumpiness), excessive worry, and emotionality (unusual laughing or weeping). It is associated with depressed liver qì, which results from deficient free coursing. It is sometimes visible on face-to-face contact.

(卑惵 bēi dié) and visceral agitation

(脏躁 zàng zào)..

Gallbladder timidity (胆怯 dǎn qiè): Also called gallbladder timidity and susceptibility to fright

(胆怯易惊 dǎn qiè yì jīng) or qì timidity

(气怯 qì qiè). Shyness, fearfulness, and lack of confidence and courage attributed to disturbance of the gallbladder’s governance of decision-making. It is often accompanied by susceptibility to fear and fright, heart vexation, insomnia, and profuse dreaming or nightmares. It is observed in gallbladder qì vacuity and in liver-gallbladder patterns involving heat.

Inspecting the Skin and Flesh

Skin

The state of the skin provides information about the state of the fluids and essence-blood. In some cases, it can indicate the presence of blood stasis.

- Dry skin is attributable to damage to fluids or to depletion of essence-blood.

- Skin that is dry and rough, forming scales, is called

encrusted skin,

and is a sign of blood vacuity with blood stasis. - Yellowing of the body and eyes (身目发黄 shēn mù fā huāng) is a sign of jaundice due to damp-heat or cold-damp affecting the liver and gallbladder. A bright coloration like tangerines is attributed to damp-heat, while a dull coloration is attributed to cold-damp.

- The skin of the face is discussed further ahead under Facial Complexion.

Red Thread Marks (红缕赤痕 hóng lǚ chì hén):

Small red markings on the surface of the skin composed of red thread-like lines up to a few millimeters long radiating from a central point. Red thread marks are a sign of blood amassment creating distension. They are called

in biomedicine.

Puffy Swelling (浮腫 fú zhǒng)

Puffy swelling

is the name given to the condition in which the face, limbs, and sometimes the whole body are swollen and enlarged, without any redness or pain on pressure. It indicates water swelling,

which is the name given to the disease so manifesting. Two kinds are distinguished: yīn water and yáng water.

- Yīn water is attributable to disorders of the kidney, lung, and spleen, and usually affects the lower limbs first (although there may be slight swelling of the eyelids at onset).

- Yáng water is attributable to water-damp and externally contracted wind, cold, dampness, heat, damp-heat or summerheat, causing non-diffusion of lung qì and triple burner congestion that prevent the free flow of water down to the bladder. Yáng water is a repletion pattern characterized by swelling of the face and upper limbs first, and is attended by aversion to cold, heat effusion, cough, painful swollen throat, and rough voidings of scant urine.

For various types of swelling, see general palpation.

Prominent Veins (青筋暴露 qīng jīn bào lù)

Enlarged blood vessels raised above the surface of the body beneath the skin. It corresponds in biomedicine to

Bruising (瘀青 yū qīng)

A bruise is an injury from a blow or impact that does not break the skin but damages the blood vessels causing blood to escape and give the affected area a green-blue coloration. Bruises are one form of blood stasis. A tendency to bruise easily is a sign of qì or blood vacuity.

Maculopapular Eruption (斑疹 bān zhěn)

rashes,

are skin conditions that erupt in the course of externally contracted disease such as measles, chickenpox, and wind papules (rubella, German measles), as well as in certain internal damage and miscellaneous diseases.

- Macules are red or purple patches under the skin, with no elevation. They indicate a severe condition.

- Papules are red and slightly elevated. They indicate a mild condition and are mostly attributed to evil heat depressed in the lung and stomach that fails to discharge outward and instead enters provisioning-blood and forces the blood to move.

- Macules and papules appearing together usually mean a severe condition.

A distinction is made between favorable and unfavorable maculopapular eruptions:

Favorable patterns: These are characterized by an eruption that is evenly distributed, of medium density, red in color, spreading from the chest and abdomen out toward the limbs, and that is accompanied by generalized heat effusion and disappears as the heat effusion abates.

Favorable patterns are observed where the disease takes its course in a patient whose right qì is strong.

Unfavorable patterns: Here, an eruption is unevenly distributed, with dense areas where the macules or papules merge and with a deep-red or purple coloration, spreading from the limbs to the chest and abdomen. Initially, there is no heat effusion, but as the eruption spreads toward the chest, generalized heat effusion develops, and consciousness becomes unclear. These are signs that the evil qì, owing to poor resistance of right qì, has fallen inward

to the interior.

Unfavorable patterns occur in patients whose right qì is weak and fails to resist the evil, allowing it to fall inward (enter the interior).

Internal damage and miscellaneous diseases may present with maculopapular eruptions, mostly indicating blood heat. If they continually appear and disappear, are purplish-red in color and if signs of blood heat are absent, they indicate the failure of qì to contain the blood or qì vacuity complicated by blood stasis. Deep-seated eruptions do not blanch when pressure is applied. Well-defined eruptions have clear edges and may be characterized by localized tissue necrosis. If the edges are not well-defined, and the color fades under pressure, the condition is mild.

Measles (麻疹 má zhěn)

Measles is a contagious disease most commonly occurring in children below the age of puberty. It mostly occurs at the end of winter or beginning of spring. The disease starts like a common cold, with cough, sneezing, runny nose with clear snivel, tearing, and heat effusion. After 2–3 days, a rash appears on the buccal mucosa (inside the mouth, on the cheek). After 3–4 days, the rash spreads. It is peach pink in color, in the form of papules shaped like sesame seeds. On the outside of the body, it starts on the hairline behind the ears, gradually spreading to the forehead, trunk, and limbs.

Chickenpox (水痘 shuǐ dòu)

The Chinese medical term for chickenpox is, literally translated, water pox.

It is an externally contracted febrile disease. It is characterized by blisters that can cover the whole body. The blisters are oval in shape, are shallow, vary in size, and easily rupture. They usually have no tip, although they sometimes have a depression at the apex. They contain clear thin fluid. They do not crust and leave no scars, unless scratched. Note that pox

(痘 dòu) loosely refers to any disease marked by pustules or papules that leave scars.

Rubella (German Measles )

In Chinese medicine, rubella is known as wind papules

(风疹 fēng zhěn). It manifests in the form of a pale-red rash composed of small, densely distributed papules associated with itching. It is attributed to external contraction of wind evil.

Prickly Heat (痱子 fèi zi, 痱瘡 fèi chuāng)

Also called heat rash.

A rash that takes the form of red papules that soon turn into small blisters associated with heat sensation and itching. It affects the face, neck, arms, chest, abdomen, and thighs. It is common in hot humid conditions in summer, especially among infants and children. It is attributed to summerheat-damp preventing the normal discharge of sweat. In biomedicine, this is called

(紅粟疹 hóng sù zhěn), which is explained as sweat trapped under the skin by clogged sweat ducts.

White Sweat Rash (白㾦 bái pèi)

Also called miliaria. White sweat rash consists of small white vesicles on the skin. These are usually small like millet seeds, elevated, slightly translucent, and without any change in skin coloration. White sweat rash often occurs in damp warmth patterns or summerheat-warmth. It is usually located on the neck but may spread to the upper arms and abdomen. It only occurs when there is sweating. Although its appearance usually indicates that damp-heat can escape from the body, it also shows that dampness evil is thick and sticky and resists transformation. For this reason, there is recurrent outthrust.

Favorable patterns: When white sweat rash takes the form of clear, plump vesicles, it is a positive sign that the damp-heat is not trapped in the body. This corresponds to miliaria crystallina, also called

Unfavorable patterns: In severe cases, the vesicles turn a dull white and contain no fluid. This is called

(枯㾦 kū pèi) and signifies exhaustion of qì and liquid.

Eczema (濕疹 shī zhěn)

A usually localized condition of the skin characterized by red patches, itching that swiftly develops into papules and blisters that on rupturing exude fluid, giving way to red, moist, ulcerating areas of skin.

Eczema arises when damp-heat combines with externally contracted wind evil and lies depressed in the skin.

Sore s (疮疡 chuāng yáng)

The main kinds of sores are welling-abscesses, flat-abscesses, clove sores, and boils are as follows. A more complete list can be found under diseases 10, external medicine.

Welling-abscess (痈 yōng): A welling-abscess takes the form of a large swelling with a clearly circumscribed base. It is hot, red, and painful. It is a yáng pattern that results from congestion of qì and blood. It occurs when patients suffering from damp-heat brewing internally contract evil toxin. This causes provisioning-defense disharmony and obstruction of the channels and network vessels. The resulting congestion allows the welling-abscess to form.

Flat-abscess (疽 jū): A flat-abscess is a diffuse swelling without any change in skin color and without a head. It is not hot and is associated with little pain. This is a yīn pattern. It arises as a result of qì and blood vacuity with congealing cold phlegm or when wind toxin and accumulated heat in the five viscera flow into the flesh and fall into the sinew and bone.

Clove sore (疔 dīng, 疔疮 dīng chuāng): A small hard sore with a deep root like a clove or nail, appearing most commonly on the face and ends of the fingers. A clove sore arises when fire toxin enters the body through a wound, and then heat brews and binds in the skin and flesh. It may also arise when anger, worry, and preoccupation or excessive indulgence in rich food or alcohol gives rise to internal heat that then accumulates in the bowels and viscera and effuses outward to the skin. Sometimes, a clove sore may have a single red threadlike line stretching from the sore toward the trunk. Clove sores can develop into a clove sore running yellow

(疔疮走黄 dīng chuāng zǒu huáng), that is, one that becomes black without pus and causes the sore toxin to penetrate the blood aspect, giving rise to high fever, shiver sweating, a red or crimson tongue, rough yellow tongue fur and a pulse that is surging and rapid or slippery and stringlike. This corresponds to

Boil (癤 jié): Boils are small round swellings with mild heat, redness, and pain. Their root does not penetrate deep into the flesh. They easily suppurate and rupture, before healing quickly. They are attributed to congestion of qì and blood that arises when summerheat-damp becomes depressed in the skin or when damp-heat brewing in the viscera effuses out to the skin.

Acne (粉刺 fěn cì): Acne is a skin condition marked by blackheads (comedones) or red papules (pimples

) that are mostly found on the face, that can be squeezed to produce an oily, chalky substance, and that can develop into pustules. Acne is most common in young people. In severe cases, pimples may be large, red, and swollen and coalesce and spread to the neck, shoulders, and back. Acne is attributed to brewing lung-stomach heat fuming the face, causing heat and stagnation of the blood. It is often found to be related to excessive consumption of rich food.

Cinnabar toxin (丹毒 dān dú): A disease characterized by sudden localized reddening of the skin, giving it the appearance of having been smeared with cinnabar; hence the name. It corresponds to (erysipelas,

but the original Chinese concept is wider in meaning, notably including cellulitis.

diabetic foot

identified in biomedicine in diabetes mellitus.

Nails

The nails are the surplus of the sinews. Their condition reflects the state of liver yīn blood.

Lusterless nails (爪甲不荣 zhǎo jiǎ bù róng): Nails that lack a fresh bright coloring and luster. They are the result of liver blood vacuity depriving the nails of nourishment. A more serious condition of dry nails (爪甲干枯 zhǎo jiǎ gān kū) is attributable to severe depletion of liver blood and liver yīn.

Inspecting Body and Bearing

This part of the examination involves inspecting the patient’s body to see whether it is thin or fat, strong or weak, and observing the patient’s physical movement.

Body

Inspection of the body chiefly provides information about the patient’s constitution and the state of the spleen and stomach.

Development and strength

- A strong body is marked by broad and full chest, large bones, firm flesh, strong sinews, and moist lustrous skin. People with such a body will be found to have great energy and a good appetite. They have healthy bowels and viscera, abundant qì and blood, and a great ability to avoid illness and recover from illness quickly when they do fall ill.

- A weak body is characterized by a narrow chest, small fine bones, emaciation, weak sinews, dry lusterless skin, poor essence-spirit, and poor appetite. People with a weak body have weak bowels and viscera, have poor resistance to disease, are prone to illness, and do not recover quickly from illness.

Body type: How fat or thin a patient has an important bearing their health. Usually this is judged intuitively by the patient’s appearance. Nowadays, Body Mass Index (BMI) calculated by the weight-to-height ratio provides a more accurate assessment, although this does not take account of constitution.

A person is fat or obese if they have a sagging belly and drooping flesh, while a person is emaciated when their sinews and bone (e.g., sinews of neck, collar bone, and ribs) are clearly visible.

- Obesity with soft flabby flesh, poor appetite, tendency to avoid physical movement, lack of strength for physical movement, breathing difficulty at the slightest exertion is described as

exuberant physique and vacuous qì

(形盛气虚 xíng shèng qì xū). This is often seen in yáng vacuity and spleen vacuity patients susceptible to phlegm, rheum, water, and dampness collecting internally. When visceral qì disorders develop, phlegm and qì become congested, giving rise to dizziness and in severe cases wind stroke. Hence, it is said thatobese people are prone to phlegm-damp and wind stroke.

- A stocky build with firm flesh, good appetite, healthy spirit, and physical strength is a sign of a strong body and abundant qì. It is not considered morbid. Illness in people with this body type usually takes the form of repletion patterns or heat patterns and is of short duration.

- A lean body with abundant energy, healthy spirit, physical strength, and good resistance to illness is healthy.

- A thin body with lack of strength, shortness of breath, and laziness to speak are usually found to suffer from earlier-heaven insufficiency with qì and blood vacuity.

- A thin body with large food intake usually indicates yīn vacuity with effulgent fire and is seen in dispersion-thirst and goiter.

- A thin body with red cheeks and dry skin usually indicates insufficiency of yīn-blood depriving the body of nourishment and is seen in the latter stages of warm disease and in pulmonary consumption. Hence it is said that

thin people are prone to vacuity fire and to consumption cough.

If they are confined to bed for a long time and their bones become like firewood (i.e., matchsticks), this indicates a critical condition of depletion of essential qì and desiccation of qì and humor.

Posture and Bearing

The posture a patient adopts, especially when lying, and the way a patient moves (or fails to move) provide important information about the yīn-yáng nature of the condition, the presence of internal wind, impediment (bì), or wilting (wěi).

Yīn and yáng patterns

- Flailing of the limbs, agitation (more physical movement than normal), talkativeness, and a tendency to throw off clothing are signs attributable to yáng patterns of heat or repletion.

- A patient who assumes a curled-up lying posture, has little desire to talk, tends to add extra layers of clothing, and displays heavy sluggish movements is suffering from a yīn pattern of cold or vacuity.

Signs associated with liver wind stirring internally and tetanic disease: Various forms of what is called spasm in biomedicine appear in tetany (also called tetanic disease

), fright wind, and wind strike. Liver wind stirring within is the pathomechanism by which these conditions most commonly arise, although lockjaw, a specific tetanic disease, is attributed to contraction of wind toxin

through wounds. See tetany, fright wind, wind stroke, and lockjaw.

- Deviated eyes and mouth (口眼喎斜 kǒu yǎn wāi xié) : The face and eyes pulled to one side of the face. This is seen in wind stroke and facial paralysis.

- Convulsions (抽搐 chōu chù) : Also called

tugging and slackening

(瘈瘲 chì zòng). Rapid involuntary movement of the limbs. Because it is caused by internal wind, it is often calledtugging wind

(抽風 chōu fēng). It is observed in fright wind attributable to extreme heat stirring wind, in lockjaw attributable to external wind toxin damage, and in epilepsy patterns, which are attributed to wind-phlegm. Convulsions with clouded spirit are calledtetanic reversal

(痉厥 jìng jué). - Arched-back rigidity (角弓反张 jiǎo gōng fǎn zhāng): Backward arching of the back, called

in biomedicine. It occurs most commonly in fright wind attributable to extreme heat engendering wind, in lockjaw attributable to external wind toxin damage, and other tetany patterns.opisthotonos - Clenched jaw (牙关紧闭 yá guān jǐn bì) : A tightly closed jaw, called

in biomedicine. This occurs most commonly in fright wind attributable to extreme heat engendering wind, in tetanic disease (including lockjaw attributable to external wind toxin damage), and in wind stroke attributable to liver yáng transforming into wind.trismus - Jerking sinews and twitching flesh (筋惕肉膶 jīn tì ròu shùn) is sporadic movement of body parts, including twitching of the eyes (tic). Wriggling of the extremities (手足蠕动 shǒu zú rú dòng) is gentle movements of the hands or fingers and feet or toes. Tremor of the extremities (手足震颤 shǒu zú zhèn chàn) is quivering motions of the extremities. These are all mild signs of liver wind stirring internally.

- Unsteady gait (步履不正 bù lǚ bù zhèng, 步履不稳 bù lǚ bù wěn) is the inability to walk smoothly and straight, indicating liver yáng transforming into wind.

- Shaking of the head (头摇 tóu yáo) is a sign of liver yáng transforming into wind.

- Hemiplegia (半身不遂 bàn shēn bú suì) is paralysis of one side of the body that occurs in wind stroke (i.e., stroke, apoplexy), attributable to liver wind stirring internally (liver yáng transforming into wind).

Signs associated with impediment (bì) include hypertonicity of the sinews (see below), swelling, rigidity, or

Signs associated with wilting (wěi): Limp weak limbs lacking in strength is a sign of wilting patterns

(wěi zhèng).

Miscellaneous

- Hypertonicity of the sinews (筋脉拘挛 jīn mài jū luán), also called

hypertonicity of the limbs

(四肢拘急 sì zhī jū jí), is tension in the sinews marked by inhibited bending and stretching. It is often attributed to liver blood vacuity, but there are numerous other causes: cold-damp, external contraction of wind-cold; damp-heat; exuberant heat; and yáng collapse and humor desertion. It may occur in impediment (bì). - Stiff nape (项强 xiàng jiàng) is stiffness and discomfort in the back of the neck. In liver disease, it is a sign of liver yáng transforming into wind. Stiff nape may also be caused by externally contracted wind-cold or wind-damp, by damage to liquid by evil heat, or by wind toxin entering wounds (lockjaw). When severe, it is often referred to as

rigidity of the nape and neck

(颈项强直 jǐng xiàng jiàng zhí), which is associated with extreme heat engendering wind or with lockjaw, which is caused by external wind toxin damage. Cramps of the lower legs (小腿转筋 xiǎo tuǐ zhuàn jīn) in patients suffering from severe vomiting and diarrhea is a sign of cholera.

Inspecting the Complexion

Inspection of the complexion may involve inspecting the complexion of the whole body. In practice, the practitioner is mostly concerned with the facial complexion, which often accurately reflects the state of qì and the blood. The Líng Shū (Chapter 4) states, The qì and blood of the twelve primary channels and the 365 network vessels [i.e., all the channels and network vessels of the body] rise to the face.

The color of the complexion is classified according to the five colors corresponding to the five phases: green-blue, red, yellow, white, and black. These are basic colors from which the infinite gamut of hues is derived. When applied to the human complexion, they take on relative significance. Thus, two people who, when healthy, have vastly different skin colors may be both described as having a white

complexion when suffering from a certain disease even though the actual color is quite different. White

here refers to a relative paling compared with the individual’s healthy complexion. A healthy Chinese complexion is of a pale ocher hue with a light reddish luster, though it may darken markedly when exposed to the sun and wind. The five colors are applied mutatis mutandis to the skins of all races.

Inspecting the complexion of the entire body involves paying attention to the presence of maculopapular eruptions and sores. See also Inspecting the Skin and Flesh above.

Significance of the Facial Complexion

The diagnostic significance of the facial complexion rests on the understanding that it reflects the health of qì and blood, the presence of disease evils, the locus of illness among the bowels and viscera, and the severity of illness.

Qì and Blood

The complexion reflects the health of qì and blood. A ruddy complexion with a moist sheen means that qì and blood are abundant. A lusterless pale-white complexion is a sign of insufficiency of qì and blood. A dull green-blue or purple complexion reflects qì stagnation and blood stasis.

Disease Evils

A red complexion indicates heat. White indicates cold. Green-blue or purple indicates qì stagnation and blood stasis. A bright yellow complexion and whites of the eyes indicates damp-heat.

Locus of Disease

The Nèi Jīng describes two schemes linking the complexion to the health of the bowels.

Color-viscus correspondence: Green-blue corresponds to the liver; red to the heart, yellow to the spleen, white to the lung, and black to the kidney. Under normal circumstances, the five colors appear faintly in the skin and sheen, reflecting how they are duly contained

within (含蓄 hán xù) and not showing through excessively. When a bowel or viscus is affected by illness, its corresponding color shows through clearly. This is called the exposure of the viscus’s true color

(真脏色外露 zhēn zàng sè wài lòu).

Correspondence of regions of the face to the bowels and viscera: The Nèi Jīng offers two schemes correspondence between regions of the face and the bowels and viscera.

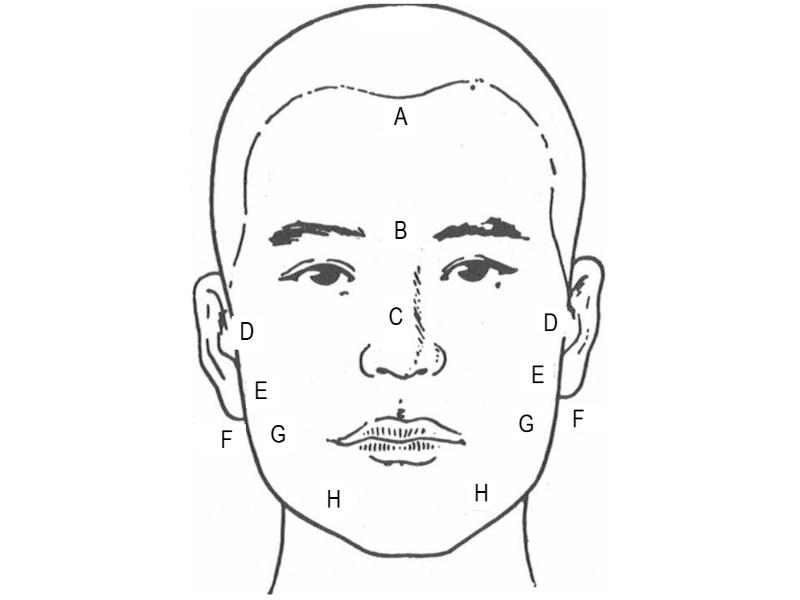

The most complex of these two schemes, presented in the Líng Shū (Chapter 49), isolates the following primary areas, each with a special name, as shown in the image below.

|

| Regions of the face according to the Líng Shū |

|---|

A: Court (廷 tíng): The forehead.

B: Gate Tower (阙 què): The glabella (the area between the eyebrows).

C: Bright Hall (明堂 míng táng): The nose.

D: Shelter (蔽 bì): Lateral cheek area at the level of the auditory meatus.

E: Fence (藩 fán): Lateral cheek area at the level of the ear lobe.

F: Ear lobe (引垂 yǐn chuí).

G: Wall (壁 bì): Lateral cheek area close to the angle of the mandible.

H: Base (基 jī): Area either side of the chin.

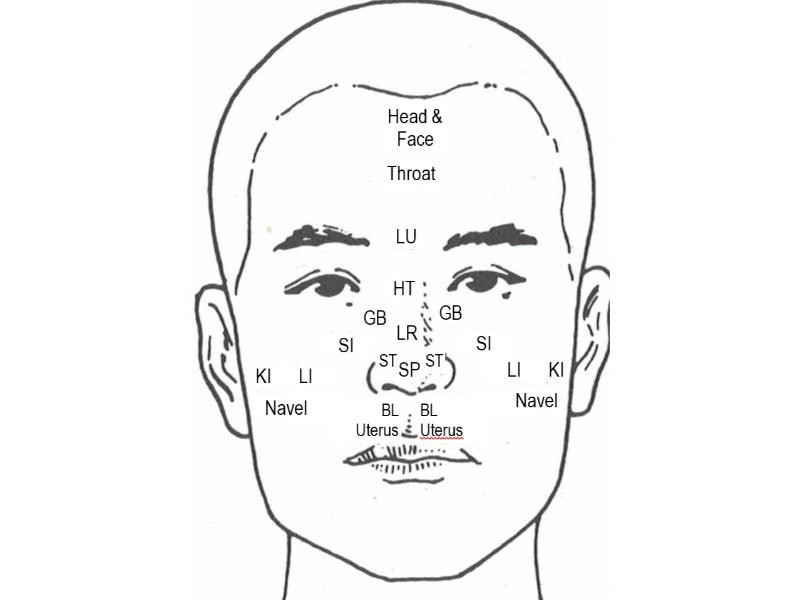

On the basis of these regions, the following correspondences (see image below):

|

| Regions of the face and their correspondences |

|---|

- Court (廷 tíng) reflects the head and face.

- Above the Gate Tower (阙上 què shàng), also called the Hall of Impression (印堂 yìn táng), reflects the throat.

- Below the Gate Tower (阙下 què xià), also called the Lower Extreme (下极 xià jí) or Mountain Root (山根 shān gēn), reflects the heart.

- Below the Lower Extreme (下极之下 xià jí zhī xià) reflects the liver. Either side of this area corresponds to the gallbladder.

- Below the Liver (肝下 gān xià), also called the Tip of the Nose (准头 zhǔn tóu, 鼻端 bí duān) or King of Face (面王 miàn wáng), reflects the spleen.

- Center (中央 zhōng yāng), also called Below the Cheekbone (颧下 quán xià) reflects the large intestine.

- Either Side of the Large Intestine (挟大肠 xié dà cháng), i.e., the lower lateral region of the cheek, reflects the kidney.

- The region above the King of Face, i.e., the area either side of the nose above its tip, reflects the small intestine.

- The region below the King of Face, also called Human Center (人中 rén zhōng) or philtrum, reflects the bladder and the uterus.

A simpler scheme presented in Sù Wèn (Chapter 32) is as follows:

- Forehead: Heart

- Nose: Spleen.

- Left cheek: Liver.

- Right cheek: Lung.

- Chin: Kidney.

These correspondence schemes are highly detailed and complex. They are not commonly used systematically in modern clinical practice. They are included in modern Chinese textbooks out of reverence for the Nèi Jīng .

Severity and Prognosis

A bright and moist color that is contained and not exposed, with a moist sheen is called a benign complexion

and is a sign of abundant qì and blood, and healthy essence-spirit. It means that the condition is mild and that the prognosis is good. A dry complexion of dull coloration in which the true color is exposed is called a malign complexion,

indicating that qì and blood are lacking and that the bowels and viscera as well as essence-spirit are severely debilitated. This is a sign of deep and severe illness with a poor prognosis.

Color and sheen have relative significance. Color is yīn and governs the blood. It reflects the state of the blood and blood flow, as well as indicating the nature and locus of illness. Sheen is yáng and governs qì. It reflects the essential qì of the bowels and viscera and the state of the fluids. Hence, color and sheen must be considered together. As regards prognosis, the presence or absence of sheen is often of greater significance than color.

Normal and Morbid Complexions

Normal Complexions (常色 cháng sè)

The complexion of a healthy person is described as being moist, lustrous, and contained

(含蓄 hán xù). A slightly moist and lustrous complexion means the essence is abundant, the spirit is healthy, qì and blood are plentiful, and bowel and visceral function is normal. Contained

means that, whatever skin pigmentation a person has, it has a healthy coloration that appears to emanate faintly from below the skin rather than being fully exposed. This is a sign that stomach qì is abundant and essential qì is contained within, rather than discharging outward. Normal complexions include the governing complexion and visiting complexions.

Governing complexion (主色 zhǔ sè): The governing complexion is the one we are born with. It is part of our constitution and remains fundamentally unchanged throughout our life. An ancient scheme of classifying constitutions according to the five phases posits that metal-type people have white skin, wood-type people have a green-blue complexion, water-type people have a slightly blackish complexion, fire-type people have a slightly red complexion, and earthy-type people have a slightly yellow complexion.

Visiting complexion (客色 kè sè): A visiting complexion is a transient variation in the complexion that arises from causes other than illness.

- Weather: The complexion naturally changes with the seasons. Thus, the complexion is slightly green-blue in spring, red in summer, yellow in late summer, white in autumn, and black in winter.

- Diurnal cycle: In the daytime, defense qì floats to the exterior, making the complexion red and moist. At night, defense qì sinks into the interior, making the complexion slightly paler and drier.

- Physical exertion: Running and other forms of physical exertion cause the complexion to redden.

- Food and drink: Alcoholic beverages cause the network vessels to dilate, making the facial complexion and the eyes red. After eating, stomach qì is abundant, giving a sheen to the complexion. Excessive eating reduces stomach qì, so the complexion loses its sheen and becomes slightly dry.

- Affect-mind: Changes in a person’s emotional state can affect the complexion. Some of the changes are not obvious, but it is worth taking note of them. Joy makes spirit qì expand so that the face becomes slightly red. Anger makes the liver qì move cross-counterflow, giving the complexion a green-blue tinge. Worry makes qì concentrate in the center, causing the complexion to become heavy and sunken. Thought causes qì to bind in the spleen, making the complexion yellow. Sorrow makes qì disperse in the interior, causing the sheen to diminish. Fear causes essence-spirit to stir and be fearful so that the complexion becomes white.

Morbid Complexions (病色 bìng sè)

Changes in the complexion that are not attributable to changes in the visiting complexion are considered morbid. Morbid complexions are dull and exposed. Dull

means lacking in moistness and luster, signifying debilitation of the essential qì of the bowels and viscera and stomach qì failing ascend to give the face a luxuriant healthy glow. Exposed

means that a complexion color is showing through on the surface. It is the outward appearance of a disease color or the true visceral color. Morbid complexions vary depending on the severity, depth, and nature of the illness, but they generally reflect the nature of the illness and the bowels or viscera affected, as will be discussed under Complexion Color below. A distinction is made between benign and malign complexions.

qì arriving

(气至 qì zhì) or getting through.

Benign complexions are seen in new illness (illness of recent onset), mild illness, and yáng patterns.

Malign complexion(恶色 è sè): A malign complexion is dry and dull. It means the essential qì of the bowels and viscera is severely debilitated, and stomach qì is unable to ascend to provide the face with luxuriance. This is often described as qì not arriving.

Malign complexions are seen in enduring illness, severe illness, and yīn patterns.

Complexion Color

Inspection of the facial complexion in modern practice mostly focuses on its color. The basic colors are white, green-blue, red, yellow, and black, but these come in various gradations.

White Complexions (面色白 miàn sè baí)

A white facial complexion

indicates vacuity, cold, or loss of blood. Distinction is made between pale-white, bright-white, and somber-white shades.

- A lusterless pale-white complexion, sometimes with a tinge of yellow (withered-yellow complexion) is a sign of dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- When accompanied by emaciation, it is a sign of provisioning-blood depletion.

- Fulminant desertion of yáng qì: A somber-white facial complexion that appears suddenly is a sign of fulminant desertion of yáng qì (in conditions called

shock

in Western medicine). - Internal cold: A somber-white complexion may also accompany severe abdominal pain or shivering attributable to interior cold. In this case, it is a sign of yīn cold congealing and stagnating.

- Wind-cold: A somber-white complexion may also be observed in externally contracted wind-cold marked by aversion to cold, shivering, and severe abdominal pain attributable to interior cold.

- Roundworm: Grayish-white macules may be seen in infantile roundworm, known as

worm macules.

Green-Blue Complexions (面色青紫 miàn sè qīng zǐ)

A green-blue facial complexion

arises as a result of severely inhibited flow of qì and blood owing to severe insufficiency of yáng qì, to exuberant cold, or to inhibited qì dynamic. Yáng qì vacuity and exuberant cold are causes of blood stasis, so a green-blue complexion characterizes blood stasis attributable to these causes. Furthermore, because when there is stoppage, there is pain,

a green-blue complexion is often observed in patients suffering from pain. Thus, a green-blue complexion is observed in blood stasis patterns, cold patterns, pain patterns, and fright wind (a disease in infants marked by convulsions and loss of consciousness). In biomedicine, green-blue complexions are seen in pulmogenic heart disease and asphyxia, cardiac failure, and cirrhosis of the liver.

- Yáng vacuity may be marked by a pale green-blue complexion.

- Fulminant desertion of heart yáng manifests in a grayish-green-blue complexion and green-blue or purple lips, with heart palpitation, oppression in the chest, and heart pain.

- Chest impediment manifests in a grayish-green-blue complexion with green-blue or purple lips, with oppression and pain in the heart region, which is mostly attributable to heart yáng vacuity with resulting blood stasis. Phlegm and cold are also possible factors. The pain is often described as stabbing pain in the

vacuous lǐ

(the apical pulse). - Cold, either externally contracted or arising internally, can present with somber-white complexion with a slight green-blue hue, accompanied by headache, generalized pain, or pain in the chest or abdomen.

- Lung qì block with severe restriction in the flow of qì and blood can present with a dark purplish-green-blue or purple complexion. This is seen in conditions that biomedicine diagnoses as

pulmogenic heart disease andasphyxia . - Kidney failing to absorb qì, which manifests in panting, can be marked by a green-blue complexion.

- Fright wind: In children, a pronounced green-blue coloration around the stem of the nose, between the eyebrows, or around the lips is a sign of fright wind. If it is green-blue verging on somber white, it is chronic fright wind; if it is green-blue with a reddish hue, it is acute fright wind attributable to extreme heat engendering wind.

Red Complexions (面色红 miàn sè hóng)

A red facial complexion

is one that is redder than normal. It indicates heat. Heat makes the blood more mobile than normal. Because heat naturally bears upward, it forces blood upward to flush the face.

Tidal reddening of the cheeks (两颧潮红 liǎng quán cháo hóng): Also called postmeridian reddening of the cheeks

(午后颧红 wǔ hòu quán hóng), or just reddening of the cheeks (quán hóng). It is a slight flushing confined to the area of the cheekbones, usually occurring in the late afternoon and evening each day. It is a sign of yīn vacuity with internal heat.

upcast yang

or vacuous yáng floating astray,

which is a critical sign of imminent outward desertion of yáng qì.

Yellow Complexions (面色黄 miàn sè huáng)

A yellow facial complexion indicates spleen vacuity with brewing dampness.

Withered-yellow facial complexion , one that is pale yellow, dry, and lusterless like withered leaves, is a sign of spleen-stomach qì vacuity and insufficiency of qì and blood.

Jaundice: A yellow complexion is a sign of jaundice in patients whose whites of the eyes (sclerae) and skin of the whole body are yellow.

- A bright orange-yellow like the color of tangerines is called

yáng yellowing

oryáng jaundice,

and is caused by damp-heat. - A dark, smoky yellow is called

yīn yellowing

oryīn jaundice.

It is attributed to depressed cold-damp causing obstruction that prevents qì and blood from providing luxuriance.

Yellow swelling (黄胖 huáng pàng): A yellow complexion with puffy swelling is called yellow swelling,

a disease attributed to the spleen failing to move and transform water-damp, which then floods the skin and flesh. It is usually caused by excessive loss of blood or depletion of qì and blood after major illness, or by spleen-stomach damage resulting from intestinal parasites. It may be seen in conditions known in biomedicine as

Black Complexions (面色黑 miàn sè heī)

A black facial complexion

indicates severe kidney vacuity, blood stasis, cold patterns, or water-rheum.

A black complexion indicates intractable or severe illness affecting the kidney. Black jaundice,

described in the Jīn Guì Yào Lüè, is a condition associated with kidney vacuity and blood stasis and is hard to cure.

Black is the color of exuberant yīn cold and water or of congealing and stagnating qì and blood. The kidney is the viscus of fire and water and is the root of the yīn and yáng of the whole body. When kidney yáng is vacuous, water-rheum fails to be transformed. Consequently, yīn cold and water become exuberant, the blood is deprived of warmth, the vessels become tense so that blood does not move freely, and the facial complexion turns black.

- A dull pale blackish facial complexion (面色黑暗淡 miàn sè àn dàn) is usually a sign of kidney vacuity.

- A dry parched black facial complexion (面黑干焦 miàn heī gān jiāo) usually indicates depletion of kidney essence and kidney yīn with vacuity fire scorching yīn.

- A soot-black facial complexion (面色黧黑 miàn sè lí heī) with

encrusted skin

(dry coarse scaly skin) is attributable to blood vacuity with blood stasis. - Black complexion around the eye sockets (眼眶周围发黑 yǎn kuāng zhōu weí fā heī) may reflect either phlegm-rheum arising from kidney vacuity water flood or cold-damp pouring downward and causing vaginal discharge.

In biomedicine, a soot-black facial complexion may be seen in chronic hyperadrenocorticism or in the final stages of cirrhosis of the liver. A dark-gray complexion may be seen in chronic kidney dysfunction. A purple-black complexion may occur in chronic cardiopulmonary dysfunctions.

Ten Principles for Inspecting the Complexion

The ten principles of inspecting the complexion were developed in the Qīng from statements in the Nèi Jīng .

Floating and sunken (浮沉 fú chén): Floating

describes a morbid complexion that appears in the exterior skin. It reflects an exterior pattern. Sunken

describes a morbid complexion that is hidden within the skin, reflecting an interior pattern.

Clear and turbid (清浊 qīng zhuó): Clear

describes a complexion that is clear and bright. It reflects a yáng pattern. Turbid

describes a murky dull complexion. It is primarily associated with yīn patterns. When a complexion changes from clear to turbid, it reflects yáng pattern giving way to a yīn pattern. When a turbid complexion becomes clear, it reflects a yīn pattern converting into a yáng pattern.

Faint and strong (微甚 weī shèn): Faint

describes a complexion that is shallow and pale. It is associated with vacuity. Strong

means deep and pronounced. It is associated with repletion. When a faint complexion becomes strong, this is vacuity converting into repletion. When a strong complexion becomes faint, this is repletion converting into vacuity.

Diffuse and dense (散抟 sàn tuán): Diffuse

describes a sparse, thinly spread coloration, which is associated with a new illness (illness of recent onset) or with an illness that is about to resolve. Dense

describes a complexion color that is thickly distributed, deep and stagnant. It is associated with enduring illness or with evils that are gradually gathering. When a dense complexion becomes diffuse, an enduring condition is about to resolve. A diffuse complexion growing in density indicates evil gathering in a condition of recent onset.

Lustrous and perished (泽夭 zé yāo): Lustrous

means moist and shiny. It means that essential qì has not been debilitated and that the illness is mild and easy to treat. Perished

means dry and dull. It means essential qì is already debilitated and that the illness is severe and hard to treat. When a lustrous complexion becomes perished, it means that the illness is severe, and the patient’s condition is becoming critical. When a perished complexion becomes lustrous, it means a favorable turn in severe illness. In terms of benign and malign complexions previously discussed, a lustrous complexion is benign, while a perished complexion is malign.

Infant’s Finger Examination

The

The finger examination provides supplementary diagnostic data that is especially useful in judging the severity of an illness. It helps compensate for difficulties of the pulse examination attributable to the infant ’s very short radial pulse, which can only be taken with a single finger. It also helps to compensate for the disturbance of the pulse that results from the distress commonly experienced by children in unfamiliar surroundings.

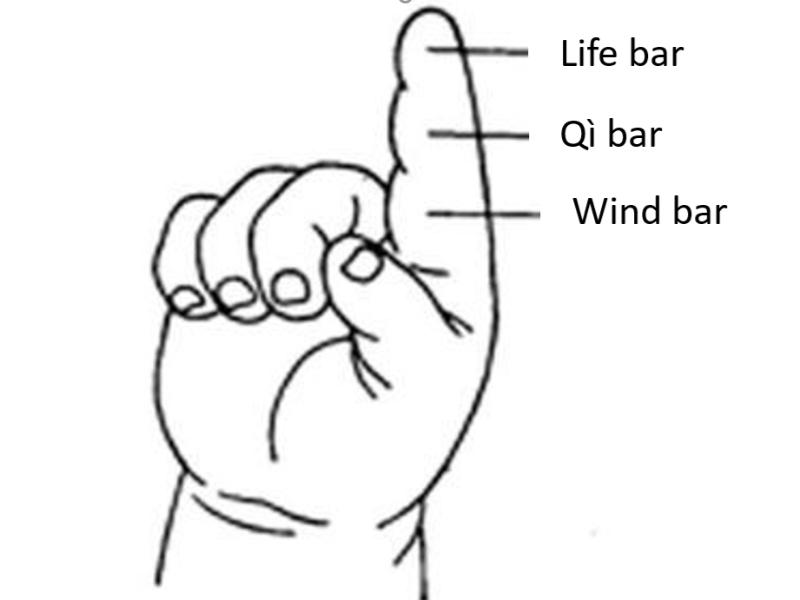

Bars

The finger is divided into three segments called bars.

- Wind bar (风关 fēng guān): This is the first segment, from the metacarpophalangeal joint to the proximal interphalangeal joint.

- Qì bar (气关 qì guān): This is the second segment, from the proximal interphalangeal joint to the distal interphalangeal joint.

- Life bar (命关 mìng guān): This is the final segment, from the distal interphalangeal joint to the fingertip.

|

| The three bars of the infant ’s index finger |

|---|

Method

The examination should be conducted in good light. The practitioner holds the child’s fingertip using her thumb and index finger. Then, using the other thumb, she gently rubs from the finger from the tip downward several times. This makes the veins more distinct.

Significance

In healthy infants, the veins appear as dimly visible, pale purple to reddish-brown lines. Generally, they are visible in the wind bar only.

Depth: Veins that are especially distinct and close to the surface indicate an exterior pattern. If the veins are bright red, they indicate contraction of an external evil. If they are located at a deeper level, an evil is present in the interior.

Color: Purplish-red veins indicate heat; green-blue veins indicate wind-cold, fright wind, a pain pattern, food damage, or ascendant counterflow of phlegm and qì. Black generally indicates blood stasis. A stagnant appearance of the veins indicating impaired blood flow throughout the veins is associated with repletion patterns such as phlegm-damp, food stagnation, or binding depression of evil heat.

Location: If the veins are distinct in the wind bar, the condition is relatively mild. If they are also distinct in the qì bar, the condition is more severe. Extension of visible veins through all the bars to the fingertip indicates a critical condition.

In sum, the depth of the veins indicates the depth of penetration to the interior. Red indicates heat; green-blue indicates cold; pale indicates vacuity; and a stagnant appearance indicates repletion. The degree of penetration from the wind to the life bars indicates the severity of the condition.

Tongue Examination

See tongue examination.

Inspecting the Head, Face, and Neck

Head

In infants, attention is paid to the size of the head and to the fontanels to determine whether development is normal or not. In any patients, the hair, face and cheeks, eyes, nose, mouth and lips, teeth and gums, throat, ears, and the neck and nape are of importance.

Head size: In infants, an excessively large or small head with low intelligence is usually attributable to earlier-heaven insufficiency and depletion of kidney essence.

Fontanels: Infants under the age of one year require inspection of the fontanels.

- A depressed anterior fontanel, called

means insufficiency of kidney essence.depressed fontanel , - A bulging anterior fontanel, called

is usually a sign of fire evil attacking upward in warm disease; it may also be attributable to accumulation of fluid. Note that it is normal for the fontanel to bulge temporarily when the infant cries.bulging fontanel , - If the fontanels fail to close by the age of one and a half, this is called retarded closure of the fontanel gates (囟门迟闭 xìn mén chí bì). As a disease name, it is known as

ununited skull

(解颅 jiě lú). This is attributable to depletion of kidney qì resulting from insufficiency of the earlier-heaven constitution or to enduring illness and lack of nourishment after birth.

Shaking of the head (头摇 tóu yáo), whether in children or adults, is a sign of liver wind stirring internally.

Hair

The hair is the surplus of the blood and the bloom of the kidney.

- Graying of the hair and hair loss (发脱 fǎ tuō) are normal in advancing years and is a sign of the waning of kidney essence. In a minority of younger individuals, graying is not pathological if no other signs of related disease are present. Premature graying of the hair has little clinical significance, although there are Chinese medical treatments for it.

- Scant dry hair indicates insufficiency of kidney qì or debilitation of qì and blood.

Face and Cheeks

The most important signs are facial swelling, swelling of the cheeks, deviated eyes and mouth, and the grimace of lockjaw.

Swelling of the cheeks: Diffuse, hot swelling of one cheek or one cheek after the other, with a red sore swollen throat, swelling of the neck, and deafness indicates mumps

(traditionally also called toad-head scourge

).

- Yīn water starts from the lower limbs, and gradually spreads upward to the face.

- Yáng water, which is much less common, starts from the upper body and gradually spreads to the lower body. See

water swelling.

Deviated eyes and mouth (口眼歪斜 kǒu yǎn wāi xié)

When one side of the face is tight and distorted, while the other side is affected by numbness and tingling, this is called deviated eyes and mouth.

The tight and distorted side is the healthy side, and the side affected by numbness and tingling is the affected side, that is, the side affected by obstruction of qì and blood. In the absence of any other signs, this is attributable to wind locally striking the channels and is relatively mild. If it is accompanied by hemiplegia and unclear spirit-mind, it is a sign of wind striking the bowels and viscera, which is more serious.

Eyes

Inspecting the eyes most often involves observing the spirit (vitality) and the physical appearance of the eye and surrounding area.

Parts of the eye: The traditionally recognized parts of the eye and their associations with the viscera are the following:

- The pupil, also called the

water wheel

(水轮 shuǐ lún), belongs the kidney. - The dark of the eye (iris), also called the

wind wheel

(风轮 fēng lún), belongs to the liver. - The white of the eye (sclera), also called the

qì wheel

(气轮 qì lún), belongs to the lung. - The canthi, also called the

blood wheel

(血轮 xuè lún), belong to the heart. - The eyelids, also called the

flesh wheel

(肉轮 ròu lún), belong to the spleen.

The eyes as the expression of the spirit: Inspecting the eyes most often involves observing the spirit. It is said that the essence of the bowels and viscera flow up to the eyes.

This is based on the observation that the eyes to some extent reflect the state of the organs. Furthermore, the eyes connect through to the brain, which is said to be the sea of marrow,

and the essence of marrow is the pupil spirit

(the pupil and the clear matter that fills the eyeball).

- When the pupils are normal in enduring or severe illness, the condition can still be treated.

- Conversely, if a patient has lusterless eyes, and tends to keep the eyes shut, taking no interest in the world or if the

eye spirit

(expression of emotion in the eyes) is abnormal, the condition is critical.

Physical appearance of the eyes: Attention is paid to the orientation of the eyes, dilation of the pupils, and the color of the whites of the eyes (sclerae).

- Forward-staring eyes (瞪目直视 dèng mù zhí shì) with clouded spirit indicates a critical condition of expiration of bowel and visceral essential qì.

Upward-staring eyes (两目上视 liǎng mù shàng shì) andsquinting (斜视 xié shì):Upward-staring eyes,

also calledupcast eyes

(戴眼 daì yǎn) means that both eyes look fixedly upward and are unable to move.Squinting

is when both eyes look fixedly to one side or the other. Both conditions are attributable to severe conditions of liver wind stirring internally. Squinting of one or both eyes may be due to earlier-heaven causes.Bulging eyes (眼球外突 yǎn qiú waì tū) are usually caused by binding depression of phlegm-fire.Dilatation of the pupils (瞳孔散大 tóng kǒng sàn dà) in severe illness may be a sign of imminent death.Contraction of the pupils (瞳孔缩小 tóng kǒng suō xiǎo) may occur in wind stroke (as a result of intracerebral hemorrhage).- Red eyes (目赤 mù chì), as visibly seen in the whites of the eyes (sclerae) and colloquially often described as blood-shot eyes (as from conjunctival hyperemia), are usually attributable to externally contracted wind-heat (

wind-fire eye

) or epidemic toxin (heaven-current red eye

), both also being referred to asfire eye.

These forms are equivalent toacute conjunctivitis orscleritis in biomedicine. Other causes include liver fire flaming upward, ascendant hyperactivity of liver yáng, liver-kidney yīn vacuity, or hyperactive heart fire. In some cases, it is associated with copious eye discharge (目眵 mù chī). Yellowing of whites of the eyes (sclerae) indicates jaundice due either to damp-heat or less commonly cold-damp.Exposure of the eyeballs (露睛 lù jīng) is failure of the eyes to fully close. In clouded sleep, it indicates severe spleen-stomach debilitation and is seen in children after severe vomiting and diarrhea, and notably in chronic spleen wind (慢脾风 màn pí fēng). Chronic spleen wind, which occurs in young children when severe vomiting or diarrhea weakens right qì, manifests in closed eyes, shaking head, dark green-blue face and lips, sweating brow, clouded spirit, hypersomnia often with exposure of the eyeballs, reversal cold of the limbs, and wriggling of the extremities.

Eyelids and surrounding area: Attention is paid to the color of the skin and to swelling, as well as to whether the eyes are sunken or bulging.

Dark rings around the eyes (眼圈晦暗 yǎn quān huì àn) indicate kidney vacuity. A darker coloration around the eyes is normal in certain dark-skinned people (notably from the Asian subcontinent).Green-blue or purple rings around the eyes (眼圈青紫 yǎn quān qīng zǐ) indicate intraorbital bleeding.Sunken eyes (目窠上微肿 mù kē neì xiàn) indicate a serious condition of damage to liquid or humor desertion.Slight puffiness around the eyes (目窠微肿 mù kē wēi zhǒng) may indicate incipient water swelling. However, debilitation of kidney qì in advancing years may be reflected in slackening and puffiness of the lower lids, which in most cases does not constitute a sign of illness.Drooping eyelids (眼睑下垂 yǎn jiǎn xià chuí): Called

in biomedicine. It is mostly attributed to earlier-heaven insufficiency and depletion of the spleen and kidney.blepharoptosis Twitching of the eyelids (目膶 mù shùn) is usually attributed to external or internal wind.

Sty (针眼 zhēn yǎn) and cinnabar eye (眼丹 yǎn dān): A small red swelling of the upper or lower eyelid with a yellow tip is a sty. More generalized swelling of the eyelid is called cinnabar eye.

Both are caused by wind-heat evil toxin or spleen-stomach heat rising to the attack the eyes.

External obstruction (外障 waì zhàng): Any condition of the eyelids, canthi, white of the eye (sclerae), or dark of the eye (iris) that obstructs vision. External obstructions include painful red swollen eyes (e.g., wind-fire eye), tearing, eye discharge, dryness of the eyes, and excrescences of the canthi (

). Most involve fire or phlegm, and less frequently, liver-kidney yīn vacuity with vacuity fire flaming upward or spleen qì vacuity.

Internal obstruction (内障 neì zhàng): Also called eye screen

(目翳 mù yī). Any condition of the pupil and inner eye obstructing vision. This includes green wind internal obstruction

(绿风内障 lǜ fēng neì zhàng), which corresponds to coin screen

(圆翳 yuán yì), which corresponds to

Coin screen (圆翳 yuán yì): A round white opacity covering the pupil below the surface of the eye, so called because it resembles a silver coin. It is one form of internal obstruction. It is usually attributed to insufficiency of the liver and kidney with yīn vacuity damp-heat or liver-channel wind-heat attacking upward. This is one of several conditions that corresponds to cataract in biomedicine.

Ears

The ears are the outer orifice of the kidney. The ear region is also the meeting place of several channels: The foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder channel, the foot greater yáng (taì yáng) bladder channel, and the foot yáng míng (yáng míng) stomach channel. Inspection of the ears mostly concerns the auricle, which is the projecting external part of the ear, and the helix, which is the rim of the auricle.

Color

- Moist red auricles are a sign of plentiful qì and blood.

- Pale auricles indicate depletion of qì and blood.

- Red swollen auricles indicate liver-gallbladder damp-heat or heat toxin attacking the upper body.

- Green-blue or blackish auricles are seen in people with exuberant internal yīn cold with severe pain.

- Burnt-black auricles indicate depletion of kidney essence, which is seen in severe illness or in advanced-stage warm disease, causing depletion of kidney yīn or in patients with

lower-burner dispersion-thirst.

- Red veins appearing behind the ears and palpable cold at the base of the ear are signs that herald measles.

Form

- Thin small auricles indicate earlier-heaven depletion and insufficiency of kidney essence.

- Withered helices (the outer rims of the auricle) and shrinking of the lobes in enduring or serious illness is a sign of qì and blood depletion and impending expiration of kidney qì.

- Encrusted skin (rough, dry, scaly skin) on the helices indicates enduring blood stasis.

Interior

- Discharge of pus from inside the ear is called

purulent ear

(聤耳 tíng ěr), which is attributed to liver-gallbladder damp-heat. In the advanced stages, it can turn from a repletion pattern into a vacuity pattern of insufficiency of kidney yīn with vacuity fire flaming upward. - Excessive accumulation of earwax is called

ceruminal congestion

(耵耳 dīng ěr), which is traditionally ascribed to wind-heat. According to modern, factors include poor aural hygiene, inflammation, and reduced movement of the lower jaw in the elderly (jaw movement normally helps to keep the ears free of wax).

Nose

inward fallof the evil, that is, its passage into the interior.

Mouth, Lips, and Jaw

Attention is paid to the color and moistness of the lips, drooling, sores, and spasm.

Color and moistness of the lips

- Pale lips are a sign of dual vacuity of qì and blood or of cold.

- Parched dry lips indicate damage to liquid.

- Red lips indicate vacuity or repletion heat. The deeper the red the more intense the heat. If the lips are also parched and dry, this means damage to liquid.

- Green-blue or purple lips appear in blood stasis or cold patterns, indicating impaired flow of qì and blood.

- Blackness around the mouth indicates that the kidney is on the verge of expiration.

- White speckles like millet seeds on the inside of the lips may indicate worm accumulation.

- Gaping mouth with closed eyes and limp hands is a sign of qì desertion.

Drooling (流涎 liú xián). See also drool

below under Inspecting Eliminated Matter at the end of this entry.

- Drooling from the corners of the mouth during sleep generally indicates spleen vacuity or stomach heat. In infants, this may be a sign of intestinal worms.

- Drooling from one side of the mouth is associated with deviated mouth in facial paralysis.

Clenched jaw (牙关紧闭 yá guān jǐn bì) occurs mostly in repletion patterns of liver wind stirring internally.

- It mostly occurs in tetanic disease (including lockjaw) and fright wind.

- It is observed with foaming at the mouth and sudden clouding collapse in epileptic seizures.

- It occurs with deviated eyes and mouth and phlegm rale in the throat in wind stroke.

Other anomalies

- Gaping corners of the mouth and shrinkage of the philtrum signify imminent desertion of right qì.

- Ulceration of the lips is usually attributable to heat brewing in the lung and stomach or to vacuity fire flaming upward.

- Sores at the side of the mouth that are red and painful are usually attributed to heat in the heart and spleen channels.

- Pursed lips in infants is a sign of

umbilical wind.

- Twitching of the corners of the mouth may portend the stirring of wind.

Teeth and Gums

The teeth are the surplus of the bone, which belongs to the kidney. The stomach is connected to the gums. Hence, disease of the teeth and gums is associated with the kidney and the stomach.

- Dry teeth indicate damage to liquid by intense heat.

Teeth as dry as old bones

indicate exsiccation of kidney yīn. - Black, eroded areas of the teeth indicate tooth decay.

- Loosening of the teeth (齿松 chǐ sōng, 牙齿松动 yá chǐ sōng dòng) occurs in insufficiency of kidney essence and in liver yīn vacuity.

Vacuity swelling of the gums , that is, slight swelling of the gums that pits when pressure is applied, indicates kidney vacuity.- Bleeding gums may be attributable to intense stomach heat, the spleen failing to control the blood or kidney yīn vacuity.

- Painful swollen ulcerating gums (牙龈肿痛溃烂 yá yín zhǒng tòng kuì làn): Mainly caused by intense stomach heat.

- Gaping gums (牙龈宣露 yá yín xuān lù) is exposure of the roots of the teeth, often associated with swelling, bleeding and putrefaction. It is associated with intense stomach heat or with insufficiency of kidney qì.

- Grinding of the teeth (齘齿 xiè chǐ) is technically called bruxism in biomedicine. Occurring in infants and children during sleep usually means stomach heat, intestinal worms, or gān accumulation (malnutrition).

Throat

The pharynx is the upper part of the throat, which is partly visible at the back of the mouth. Inspection of the throat is mostly concerned with red sore swollen throat or throat nodes. In Chinese texts, sore throat as a disease category is often referred to as throat impediment

(喉痹 hóu bì), reflecting how the condition makes swallowing difficult. The Chinese equivalent of sore throat

is (喉咙痛 hóu lóng tòng), but in Chinese medical texts, symptom descriptions pertaining to inspection are usually more detailed, indicating redness, swelling, pain, dryness, and the presence of any other anomalies.

- A painful red swollen throat is usually attributable to lung or stomach heat flaming upward in warm disease.

- Painful red swollen

(喉核 hóu hé, tonsils) are a sign ofthroat nodes throat moth

(喉蛾 hóu é), also calledbaby moth

(乳蛾 rǔ é), which corresponds to tonsillitis in biomedicine. This is caused by of lung-stomach heat flaming upward. The additional presence of yellowish-white putrefaction speckles indicates heat toxin. - A dry painful red pharynx with only slight swelling indicates yīn vacuity with effulgent fire.

- A slightly red and slightly swollen sore throat with grayish-white putrefaction speckles or patches that are not easily removed may indicate diphtheria. It is attributable to dryness-heat scorching lung-stomach yīn liquid.

- A white membrane covering the lining of the throat indicates diphtheria.

Neck and Nape

Problems associated with the neck include goiter, scrofula, and phlegm nodes, and stiff nape. Man’s Prognosis is a pulse felt on the neck that is sometimes used in diagnosis.

Lump at the front of the neck (颈前有肿块 jǐng qián yǒu zhǒng kuài) taking the form of a diffuse swelling on one or both sides of the anterior aspect of the neck that moves up and down as the patient swallows indicates goiter (瘿病 yǐng bìng, 瘿瘤 yǐng liú), colloquially known as fat neck

or big neck

(颈粗 jǐng cū, 大脖子 dà bó zi) in Chinese. Goiter is attributed to various factors including depressed liver qì, phlegm, blood stasis, and/or heat. See goiter.

Stiff nape (項強 xiàng jiàng): Stiff nape may be visible to the practitioner when it inhibits movement of the head, but it is a subject for the inquiry examination. It has the following significances:

- Stiff nape with mild pain, accompanied by aversion to cold and floating pulse, is attributable to wind-cold invading the greater yáng (tài yáng) channel.

- Stiff nape with aversion to cold and heat effusion, head heavy as if swathed, aching limbs, fixed heavy joint pain, white tongue, and floating pulse is attributed to external contraction of wind-damp.

- Stiff nape with pronounced pain, accompanied by vigorous heat effusion and clouded spirit, is attributable to warm heat evil scorching yīn humor, depriving the sinews of nourishment.

- Stiff nape after waking is called

crick in the neck

(torticollis in Western medicine) and is attributable to poor sleeping posture. - Stiff nape with dizziness, distension in the head, headache, numbness of the limbs, and unsteady gait indicates liver yáng transforming into wind.

- Severe stiff of the nape, referred to as

rigidity of the nape and neck

(颈项强直 jǐng xiàng jiàng zhí), is associated with extreme heat engendering wind observed in wind fright. It may also be a sign of lockjaw, which is caused by a virulent form of external wind calledwind toxin.

Man’s Prognosis (人迎 rén yíng): The places where the pulse can be felt at the external carotid artery is called Man’s Prognosis, which is an acupuncture point (rén yíng, ST 9). This term refers to the pulse felt at the external carotid artery. When Man’s Prognosis pulse is conspicuously strong and accompanied by cough, panting, or water swelling, this is usually attributable to heart-lung qì debilitation or heart-kidney yáng debilitation.

Inspecting the Chest, Abdomen, Back, and Lumbus

Chest

A normal chest is symmetrical and has a left-right diameter that is greater than the front-back (anteroposterior) diameter, although in children and the elderly, the front-back diameter may be equal or greater than the left-right diameter.

Pigeon chest (鸡胸 jī xiōng) and chicken chest

in Chinese, is the protrusion of the lower part of sternum giving the appearance of a chicken breast. Funnel chest is a concave depression of the sternum. Both due to earlier-heaven insufficiency or poor later-heaven nutrition affecting bone development.

Breathing

The normal rate of respiration is 16–18 times per minute. Men and children tend to breathe with their abdomen, while women tend to breathe with their chest. For more information about breathing, see

- Increased chest breathing and decreased abdominal breathing indicates an abdominal disorder. It is seen in drum distension patients and in patients with accumulations and gatherings. It may also be seen in pregnancy.

- A decrease in chest breathing and an increase in abdominal breathing indicate a chest disorder. It is seen in pulmonary consumption, suspended rheum, and people who have suffered chest injuries.

- Asymmetrical breathing in which there is greater movement on one side of the chest is seen in suspended rheum or what biomedicine calls lung tumors.

- Prolonged inhalation means that inhalation is difficult. This is accompanied by abnormal depressions above the sternum, in the supraclavicular fossae, and between the ribs.

- Prolonged exhalation means that exhalation is difficult. This is accompanied by abnormal gaping mouth and bulging eyes and inability to lie flat. It is seen in wheezing disease and in pulmonary distension.

- Hasty breathing with pronounced expansion and contraction of the chest is mostly seen in repletion heat patterns arising when evil head and phlegm-turbidity invade the lung and disturb the lung’s depurative downbearing and diffusion function.

- Faint breathing with indistinct movement of the chest is mostly seen in vacuity cold patterns arising as a result of depletion of the lung qì or qì-vacuity constitution.

- Irregular breathing where breathing goes from deep to shallow and stops before starting again or where breathing just pauses now and again indicates a severe condition of debilitation of lung qì.

Abdomen

The main morbid signs are concave abdomen, bulging abdomen prominent green-blue vessels, and umbilical anomalies.

- A concave abdomen with general emaciation is attributable to severe spleen-stomach vacuity with insufficiency of qì and blood or to excessive vomiting and diarrhea in disease of recent onset causing major damage to liquid and humor.

- A concave abdomen with encrusted skin, in severe cases allowing the spine to be felt, is seen in highly emaciated bedridden patients and indicates expiration of essential qì.

- If it is accompanied by emaciated limbs, it is usually drum distension disease, which arises when depressed liver qì and dampness give rise to static blood.

- If the abdomen is distended and there is generalized swelling, this is usually water swelling disease, which arises a result of disorders of the lung, spleen, and kidney causing water-damp to spill into the flesh.

- Localized distension in the abdominal region is a sign of concretions, conglomerations, accumulations, or gatherings (abdominal masses).

Back and Lumbus

Deformities of the spine : These include kyphosis (hunchback, humpback), scoliosis (abnormal sideways curvature), lordosis (excessive inward curvature of the lower back), and flat back (lack of curvature). These are attributed to depletion of kidney qì, poor development, diseases of the spine, external injury, poor posture, or aging.

Inspecting the Limbs

Abnormal Form

- Enlarged red swollen knees with difficulty bending and stretching are seen in heat impediment (热痹 rè bì), which develops when wind and dampness remain depressed for a long time and transform into heat.

- Enlarged swollen knees with emaciated calves is called

crane’s-knee wind

(鹤膝风 hè xī fēng), which is mostly attributed to cold-damp lodging for a long time with qì-blood vacuity.

Deformities of the legs: These include knock-knee, bowleg, inversion of the foot (pes varus), and eversion of the foot (pes valgus). These are all attributed to poor development resulting from earlier-heaven insufficiency or poor later-heaven nourishment and resultant weakness of kidney qì.

Abnormal Movement

See Inspecting Body and Bearing above.

Inspecting the Two Yīn

The two yīn are the genitals (anterior yīn) and anus (posterior yīn).

Anterior Yīn

Inspection of the anterior yīn in males involves inspection of the penis, scrotum, and testicles for possible swellings, lumps, sores, or other anomalies. In women, it involves inspecting the labia and clitoris.

Painful swollen testicles (睾丸肿痛 gāo wán zhǒng tòng) with redness of the scrotum is a sign of liver-gallbladder damp-heat pouring downward.

Swelling of the scrotum (阴囊肿大 yīn náng zhǒng dà): Swelling of the scrotum without redness or itching may indicate yīn swelling, water mounting, or foxlike mounting.

Yīn swelling (阴肿 yīn zhǒng) is a local manifestation of severe generalized water swelling. This is easily distinguished from the following types of swelling of the scrotum by the presence of water swelling in other parts of the body.- Water mounting (水疝 shuǐ shàn), corresponding to scrotal

hydrocele in biomedicine, is a swollen scrotum that feels full of water that appears orange and translucent under a light transmission test. In the light transmission test, a sheet of non-translucent paper is rolled into a tube, and one end of it is pressed against one side of the scrotum. When a flashlight is pressed against the other side of the scrotum, the amount of light appearing in the paper tube indicates the degree of translucence of the scrotum. In water mounting, the paper tube shows an orange light, indicating a high degree of translucence. It is attributed to water-damp pouring downward or to contraction of wind, cold, or damp evils. - Foxlike mounting (狐疝 hú shàn): Also called

mounting qì

(疝气 shàn qì) orslumping mounting