Search in dictionary

Tongue examination

舌诊 〔舌診〕 shé zhěn

The tongue examination developed gradually over the centuries with contributions from numerous medical scholars. Its present form is thus the culmination of rich experience in observation of the tongue.

The tongue provides some of the most important data for diagnosis. It objectively reflects the degree of heat or cold and the depth of penetration of evils. Changes in the appearance of the tongue are particularly pronounced in externally contracted febrile disease and disorders of the spleen and stomach. It is said that the tongue is the shoot of the heart

and the tongue is the external indicator of the spleen and stomach.

The tongue reacts more slowly than the pulse to changes in the body, but tongue diagnosis is much easier to learn than pulse diagnosis. The tongue is a consistent and stable indicator of internal conditions, but conditions of recent onset may not cause changes to the tongue immediately.

In clinical practice, serious illnesses are not necessarily reflected in changes in the appearance of the tongue. Moreover, healthy individuals may show abnormal changes in the appearance of the tongue. Therefore, the data provided by the tongue examination must be carefully weighed against the other signs, the pulse, and the patient’s history before an accurate diagnosis can be made.

Method

A distinction is made between the tongue body and tongue fur. Examination of the tongue body involves observing color, form, bearing, and movement. Examination of the tongue fur involves observing color, texture, and shape.

When embarking on the tongue inspection, try to make patients feel comfortable about extending their tongue for you. Most people feel a little uncomfortable about showing their tongue, and a pleasant manner helps to overcome the reluctance. Inspect the tongue carefully. If necessary, allow the patient to rest for a few seconds before continuing.

When examining the tongue, the following four points should be kept in mind.

Light

The tongue examination should be conducted in adequately lit surroundings with light shining directly into the mouth. Inadequate lighting may blur color differences, such as between yellow and white or red and purple.

Stained Tongue Fur

Some foods and medicines affect the color of the fur and may drastically alter the diagnosis. Milk and soy milk stain the tongue fur white. Tea, coffee, and tobacco cause brown stains. Egg yolk, oranges, and huáng lián (Coptidis Rhizoma, coptis) leave yellow stains. Staining normally affects the surface of the fur and is gradually washed away by saliva. If in doubt, the practitioner should ask the patient if they have eaten anything that might cause staining.

Bearing of the Tongue on Extension

The patient is asked to extend their tongue. It should be relaxed and flat when extended. Forced or tense protraction my deepen the color of the tongue.

Miscellaneous Factors

Certain foods and illness-related handicaps can cause changes to the tongue body and especially the tongue fur, which should not be mistaken to reflect internal morbidity.

- Consumption of rough foodstuffs or chewing gum may remove the tongue fur and deepen the color of the tongue body.

- Patients with missing teeth may tend to chew food on one side of the mouth, which may cause irregularities in fur distribution.

- In wind stroke patients, motor impairment of the tongue may cause an increase in tongue fur.

- In patients tending to breathe through the mouth owing to nasal congestion or other factors, the surface of the tongue may be abnormally dry.

- Fat people tend to have large and pale tongues. Thin people tend to have thin and slightly red tongues.

- Old people tend to have tongue fissures and less pronounced papillae (the small protuberances on the tongue surface).

- Dry climates and weather can make the tongue fur thinner and drier; humid climates and weather can make the tongue fur thicker and moister.

- The tongue fur may be thicker after getting up in the morning than in the evening.

Inspecting the Form of the Tongue

Inspecting the tongue form mainly involves looking for enlargement, shrinkage, speckles, prickles, or smoothness and bareness.

Toughness and Softness

Two general tendencies in tongue forms are toughness

and softness.

- A

ortough tongue somber-tough tongue

(老舌 lǎo shé, 舌质苍老 shé zhì cāng lǎo) is one that has a coarse surface and is hard and compact with a dull somber hue. A tough tongue indicates intense heat causing damage to the fluids. - A

orsoft tongue tender-soft tongue

(嫩舌 nèn shé, 舌质娇嫩 shé zhì jiāo nèn) is one that is tender in the sense of soft like a baby’s flesh (not tender in the sense of painful); it is slightly puffy and fat, and the muscle of the tongue is not tense. It indicates depletion of qì and blood or else vacuous yáng failing to move fluids so that water-damp collects and spreads into the tongue.

Enlarged Tongue (胖大舌 pàng dà shé); Dental Impressions on the Margins of the Tongue (舌边齿痕 shé biān chǐ hén)

An enlarged tongue

is similar to a tender-soft tongue and is larger than normal. It presses against the teeth and thus is often accompanied by dental impressions (teeth marks) on the margins. It indicates vacuous yáng failing to move fluids so that water-damp collects and spreads into the tongue.

- A pale-white tender-soft enlarged tongue with watery glossy tongue fur is qì vacuity, yáng vacuity, and fluids collecting internally (water-damp and phlegm-rheum). It is often seen in spleen vacuity or spleen-kidney yáng vacuity.

- An enlarged tongue that is pale red or red, with a slimy yellow tongue fur indicates spleen-stomach damp-heat contending with phlegm turbidity.

- A tongue that is not enlarged but has dental impressions on its margins is a sign of dual vacuity of qì and blood.

In biomedicine, tongue enlargement may be seen in myxedema, chronic nephritis, and chronic gastritis and is attributed to hyperplasia of the connective tissue, tissue edema, or disturbances of blood or lymph drainage.

Cautionary note: A pale enlarged tongue with dental impressions is markedly different from a swollen tongue.

Swollen Tongue (舌腫 shé zhǒng)

A

is an enlarged tongue that fills the mouth and that tends to be tense and stiff (in contrast to an enlarged tongue, which is soft). In severe cases, it is red and painful, preventing the patient from closing her mouth properly. It is usually a sign of an exuberant warm heat evil or heart fire flaming upward. In either case, it may be complicated by liquor toxin in heavy drinkers (so it is important to ask about drinking habits). It may also be a sign of poisoning.

Shrunken Tongue (舌瘦癟 shé shòu biě)

A thin shrunken tongue indicates insufficiency of yīn liquid or dual vacuity of yīn and qì. A shrunken tongue attributable to damage to yīn humor by exuberant heat is crimson (deep red) and dry. In dual qì and yīn vacuity, the tongue is pale in color.

Modern clinical observation shows that shrinkage generally occurs in the latter stages of externally contracted febrile disease and in conditions biomedicine calls pulmonary tuberculosis and advanced carcinoma. It is explained by atrophy of the lingual muscle and epithelium attributable to malnutrition.

Fissured Tongue (裂紋舌 liè wén shé):

Fissures are clefts in the tongue body. They vary in depth and direction. Occurring with a dry tongue fur, they indicate insufficiency of fluids. They may also occur in exuberant heat patterns in conjunction with a crimson tongue.

Biomedicine attributes fissures to atrophy chiefly associated with chronic glossitis and in 0.5% of cases with causes wholly unrelated to disease.

Speckles and Prickles on the Tongue (点刺 diǎn cì, 芒刺 máng cì):

Red speckles and fine prickles appear on the tip or margins of the tongue and indicate exuberant heat. They occur in various externally contracted febrile diseases, especially yáng míng (yáng míng) repletion heat patterns and patterns involving maculopapular eruptions. Speckles and prickles, in some cases associated with pain in the tongue, may also occur in patients suffering from insomnia or constipation or those working late at night.

Small purple speckles on the upper or lower surface of the tongue are a sign of blood stasis are called stasis speckles on the tongue (舌有瘀点 shé yǒu yū diǎn).

Biomedicine attributes speckles and prickles to an increase in the size and number of fungiform papillae.

Tongue Sore s (舌疮 shé chuāng)

Sores on the tongue usually the size of millet seeds appearing anywhere on the tongue are most commonly associated with intense heart fire, in which case they tend to protrude from the tongue surface and be painful. They may also be due to lower burner yīn vacuity with vacuity fire floating upward, in which case they are pitted and not painful.

Smooth Bare Tongue (光滑舌 guāng huá shé)

A completely smooth tongue, free of liquid and fur, is sometimes called a mirror tongue

and indicates severe yīn humor depletion. A smooth red or deep-red tongue indicates damage to yīn by intense heat. A smooth tongue that is pale in color indicates damage to both qì and yīn.

According to modern clinical observation, a smooth tongue is mostly associated with advanced-stage glossitis but may also be seen in vitamin B deficiency, anemia, and advanced stages of certain diseases. It is attributable to shrinkage of the filiform and fungiform papillae.

Sublingual Vessels (舌下脈絡 shé xià mài luò)

The sublingual network vessels (veins) also demand attention. When the patient lifts the tip of her tongue, you should see two veins on either side. The branches of the veins should not be conspicuous, and there should be no stasis speckles. The color, length, breadth, form, and color of the sublingual vessels provide information mostly about the presence of qì and blood vacuity and the presence of yīn evils such as phlegm and especially blood stasis.

- When the vessels appear short and pale red with inconspicuous branches and the sublingual surface appears generally pale, this is a sign of qì and blood vacuity.

- Green-blue or pale purple veins that are tight and straight are usually attributed to congealing cold and blood stasis or to yáng vacuity and inhibited flow of qì and blood.

- Green-blue or purple veins that are dilated and enlarged are usually attributable either to phlegm-heat causing internal obstruction or to congealing cold with static blood.

- Stasis speckles indicate nascent blood stasis.

- When the veins are varicose (contorted) in appearance, this is a sign of qì stagnation and blood stasis.

Inspecting the Bearing of the Tongue

Attention is paid to the presence of stiffness, limpness, trembling, deviation, contraction, and agitation.

Stiff Tongue (舌强 shé jiàng)

A stiff tongue

is one that moves sluggishly, inhibiting speech and that cannot be extended and retracted easily. It is seen in heat entering the pericardium, high fever with damage to liquid, or wind-phlegm obstructing the network vessels.

- Heat entering the pericardium in warm disease manifests in a stiff tongue that is red or crimson in color and accompanied by unclear spirit mind.

- Damage to liquid in externally contracted disease is marked by a stiff tongue that is red and dry.

- Wind-phlegm obstructing the network vessels in wind stroke is marked by stiff tongue preventing normal speech and accompanied by deviated eyes and mouth, hemiplegia, with a thick slimy tongue fur.

- Note that the sudden appearance of a stiff tongue with numbness and tingling of the limbs and dizziness may portend wind stroke.

Limp Tongue (舌痿 shé wěi)

A limp tongue is one that is soft and floppy, moves with difficulty, cannot be forcefully extended, and makes speech difficult. It is attributed to the sinews being deprived of nourishment.

- A tongue that gradually becomes limp and that is pale white in color is caused by dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- A tongue that gradually becomes limp and that is red or crimson in color results from extreme depletion of yīn.

- In an illness of recent onset, a tongue that is red and dry and suddenly becomes limp is a sign of heat causing damage to liquid.

Trembling Tongue (舌顫 shé chàn)

A trembling tongue

or tremorous tongue

is one that trembles. It is usually attributed to liver wind stirring internally, stemming either from blood vacuity engendering wind or from extreme heat engendering wind. The differentiation rests on tongue color:

- If pale white, a trembling tongue indicates blood vacuity engendering wind.

- If red or crimson, it indicates extreme heat engendering wind.

Deviated Tongue (舌偏 shé piān)

A deviated tongue

is one that when extended tends to one side or another. It is usually attributed to liver wind stirring internally with static blood or phlegm that causes obstruction on one side of the tongue (the limp side is the obstructed side). A deviated tongue occurs in wind stroke and, like a stiff tongue, may portend that condition.

Contracted Tongue (舌短 shé duǎn)

A contracted tongue

is one that is curled up and cannot be extended easily. In severe cases, the patient has difficulty pressing her tongue against her teeth. It is a critical sign in most cases.

- A contracted tongue that is pale and moist is attributed to cold congealing in the vessels or fulminant yáng qì desertion.

- A contracted tongue with a slimy tongue fur is usually attributable to phlegm-damp causing internal obstruction.

- A contracted tongue that is red or crimson is attributable to damage to liquid in warm disease.

- In some cases, a congenitally short frenulum can cause a contracted tongue.

Protruding or Agitated Tongue (吐弄舌 tǔ nòng shé)

Protruding and agitated tongues

are ones that are constantly being extended and retracted. When the patient frequently extends the tongue and retracts it slowly, this is a protruding tongue (吐舌 tǔ shé)

. When she extends it a little and then retracts it or keeps moving the tongue up and down or side to side, licking the lips, this is called an agitated tongue

or

(弄舌 nòng shé).

- A protruding tongue is attributed to epidemic toxin attacking the heart or to impending expiration of right qì.

- An agitated tongue is a sign of retarded mental development in children or a sign of impending internal wind.

- Both conditions can be attributable to spleen-stomach heat that damages the liver and sinews, causing liver wind to stir internally.

Inspecting the Color of the Tongue

The normal color of the tongue is a pale red. In tongue diagnosis pale

or pale white

denotes any color paler than normal, while red

denotes any color deeper than normal. If considerably deeper, it is described as crimson.

A green-blue or purple

tongue is a red tongue with a green-blue or deep purplish-blue hue.

Changes in the color of the tongue body reflect the state of qì and blood and the severity of the illness.

In biomedicine, changes in the tongue color are explained by changes in blood chemistry, blood viscosity, and by the hyperplasia or atrophy of epithelial cells.

A Pale-Red Tongue (舌淡紅 shé hóng)

Pale red

is the normal color of the tongue fur. However, it is also seen in numerous pathological conditions in combination with abnormal tongue furs, as described under Tongue and Fur Combinations below.

A Pale Tongue (舌淡 shé dàn)

A pale tongue,

also called a pale-white tongue,

is one that is paler than normal. It is a sign of depletion of qì and blood or debilitation of yáng qì, i.e., vacuity patterns or cold patterns.

- A pale tongue that is shrunken usually signifies dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- A pale tongue that is slightly enlarged and tender-soft like the raw meat of a chicken breast, in some cases with dental impressions (teeth marks), is attributable to yáng qì debilitation.

A Red or Crimson Tongue (舌红绛 shé hóng jiàng)

A red tongue

is a tongue redder than normal. A deep-red tongue is called a crimson tongue.

Both mean heat, either vacuity heat or repletion heat. The added depth of color of crimson indicates heat in the provisioning or blood aspect (repletion heat).

Generalized redness

- A bright-red tongue with a dry yellow fur is a sign of intestinal heat bowel repletion.

- A crimson tongue is seen when heat enters provisioning-blood in warm disease.

- A pinkish-red or crimson tongue with little or no fur is observed in yīn vacuity with effulgent fire.

- A red-tipped tongue (舌尖红 shé jiān hóng): A tongue that is redder at the tip than in other parts. It is most commonly associated with hyperactive heart fire.

Localized redness

- When only the tip of the tongue is red, this signifies hyperactive heart fire (remember that the tongue is the sprout of the heart).

- When the margins of the tongue are red, this means exuberant liver-gallbladder heat.

- When the tongue is red in the center, this signifies exuberant center burner heat.

Green-Blue or Purple Tongue (舌青紫 shé qīng zǐ)

A

or purple tongue

refers to a tongue whose entire surface is green-blue or purple. It may be observed in both heat or cold patterns and in blood stasis patterns.

- A dry crimson-purple tongue is a sign of intense heat toxin penetrating deep into provisioning-blood and inhibiting the flow of qì and blood.

- A generalized green-blue or purple coloration indicates severe blood stasis.

- Purple macules indicate less severe or localized blood stasis.

- A glossy green-blue or purple tongue characterizes cold patterns caused by failure of yáng qì to warm and move the blood.

- A pale purple tongue that is moist indicates exuberant internal yīn cold inhibiting qì and blood and causing stasis and stagnation in the blood vessels.

Inspecting the Bearing of the Tongue

Attention is paid to the presence of stiffness, limpness, trembling, deviation, contraction, and agitation.

Stiff Tongue (舌强 shé jiàng)

A stiff tongue

is one that moves sluggishly, inhibiting speech and that cannot be extended and retracted easily. It is seen in heat entering the pericardium, high fever with damage to liquid, or wind-phlegm obstructing the network vessels.

- Heat entering the pericardium in warm disease manifests in a stiff tongue that is red or crimson in color and accompanied by unclear spirit mind.

- Damage to liquid in externally contracted disease is marked by a stiff tongue that is red and dry.

- Wind-phlegm obstructing the network vessels in wind stroke is marked by stiff tongue preventing normal speech and accompanied by deviated eyes and mouth, hemiplegia, with a thick slimy tongue fur.

- Note that the sudden appearance of a stiff tongue with numbness and tingling of the limbs and dizziness may portend wind stroke.

Limp Tongue (舌痿 shé wěi)

A limp tongue is one that is soft and floppy, moves with difficulty, cannot be forcefully extended, and makes speech difficult. It is attributed to the sinews being deprived of nourishment.

- A tongue that gradually becomes limp and that is pale-white in color is caused by dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- A tongue that gradually becomes limp and that is red or crimson in color results from extreme depletion of yīn.

- In an illness of recent onset, a tongue that is red and dry and suddenly becomes limp is a sign of heat causing damage to liquid.

Trembling Tongue (舌顫 shé chàn)

A trembling tongue

or tremorous tongue

is one that trembles. It is usually attributed to liver wind stirring internally, stemming either from blood vacuity engendering wind or from extreme heat engendering wind. The differentiation rests on tongue color:

- If pale-white, a trembling tongue indicates blood vacuity engendering wind.

- If red or crimson, it indicates extreme heat engendering wind.

Deviated Tongue (舌偏 shé piān)

A deviated tongue

is one that when extended tends to one side or another. It is usually attributed to liver wind stirring internally with static blood or phlegm that causes obstruction on one side of the tongue (the limp side is the obstructed side). A deviated tongue occurs in wind stroke and, like a stiff tongue, may portend that condition.

Contracted Tongue (舌短 shé duǎn)

A contracted tongue

is one that is curled up and cannot be extended easily. In severe cases, the patient has difficulty pressing her tongue against her teeth. It is a critical sign in most cases.

- A contracted tongue that is pale and moist is attributed to cold congealing in the vessels or fulminant yáng qì desertion.

- A contracted tongue with a slimy tongue fur is usually attributable to phlegm-damp causing internal obstruction.

- A contracted tongue that is red or crimson is attributable to damage to liquid in warm disease.

- In some cases, a congenitally short frenulum can cause a contracted tongue.

Protruding or Agitated Tongue (吐弄舌 tǔ nòng shé)

Protruding and agitated tongues

are ones that are constantly being extended and retracted. When the patient frequently extends the tongue and retracts it slowly, this is a protruding tongue (吐舌 tǔ shé)

. When she extends it a little and then retracts it or keeps moving the tongue up and down or side to side, licking the lips, this is called an agitated tongue

or

(弄舌 nòng shé).

- A protruding tongue is attributed to epidemic toxin attacking the heart or to impending expiration of right qì.

- An agitated tongue is a sign of retarded mental development in children or a sign of impending internal wind.

- Both conditions can be attributable to spleen-stomach heat that damages the liver and sinews, causing liver wind to stir internally.

Inspecting the Color of the Tongue

The normal color of the tongue is a pale red. In tongue diagnosis pale

or pale-white

denotes any color paler than normal, while red

denotes any color deeper than normal. If considerably deeper, it is described as crimson.

A green-blue or purple

tongue is a red tongue with a green-blue or deep purplish-blue hue.

Changes in the color of the tongue body reflect the state of qì and blood and the severity of the illness.

In biomedicine, changes in the tongue color are explained by changes in blood chemistry, blood viscosity, and by the hyperplasia or atrophy of epithelial cells.

A Pale-Red Tongue (舌淡紅 shé hóng)

Pale red

is the normal color of the tongue fur. However, it is also seen in numerous pathological conditions in combination with abnormal tongue furs, as described under Tongue and Fur Combinations below.

A Pale Tongue (舌淡 shé dàn)

A pale tongue,

also called a pale-white tongue,

is one that is paler than normal. It is a sign of depletion of qì and blood or debilitation of yáng qì, i.e., vacuity patterns or cold patterns.

- A pale tongue that is shrunken usually signifies dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- A pale tongue that is slightly enlarged and tender-soft like the raw meat of a chicken breast, in some cases with dental impressions (teeth marks), is attributable to yáng qì debilitation.

A Red or Crimson Tongue (舌红绛 shé hóng jiàng)

A red tongue

is a tongue redder than normal. A deep-red tongue is called a crimson tongue.

Both mean heat, either vacuity heat or repletion heat. The added depth of color of crimson indicates heat in the provisioning or blood aspect (repletion heat).

Generalized redness

- A bright-red tongue with a dry yellow fur is a sign of intestinal heat bowel repletion.

- A crimson tongue is seen when heat enters provisioning-blood in warm disease.

- A pinkish-red or crimson tongue with little or no fur is observed in yīn vacuity with effulgent fire.

- A red-tipped tongue (舌尖红 shé jiān hóng): A tongue that is redder at the tip than in other parts. It is most commonly associated with hyperactive heart fire.

Localized redness

- When only the tip of the tongue is red, this signifies hyperactive heart fire (remember that the tongue is the sprout of the heart).

- When the margins of the tongue are red, this means exuberant liver-gallbladder heat.

- When the tongue is red in the center, this signifies exuberant center burner heat.

Green-Blue or Purple Tongue (舌青紫 shé qīng zǐ)

A

or purple tongue

refers to a tongue whose entire surface is green-blue or purple. It may be observed in both heat or cold patterns and in blood stasis patterns.

- A dry crimson-purple tongue is a sign of intense heat toxin penetrating deep into provisioning-blood and inhibiting the flow of qì and blood.

- A generalized green-blue or purple coloration indicates severe blood stasis.

- Purple macules indicate less severe or localized blood stasis.

- A glossy green-blue or purple tongue characterizes cold patterns caused by failure of yáng qì to warm and move the blood.

- A pale purple tongue that is moist indicates exuberant internal yīn cold inhibiting qì and blood and causing stasis and stagnation in the blood vessels.

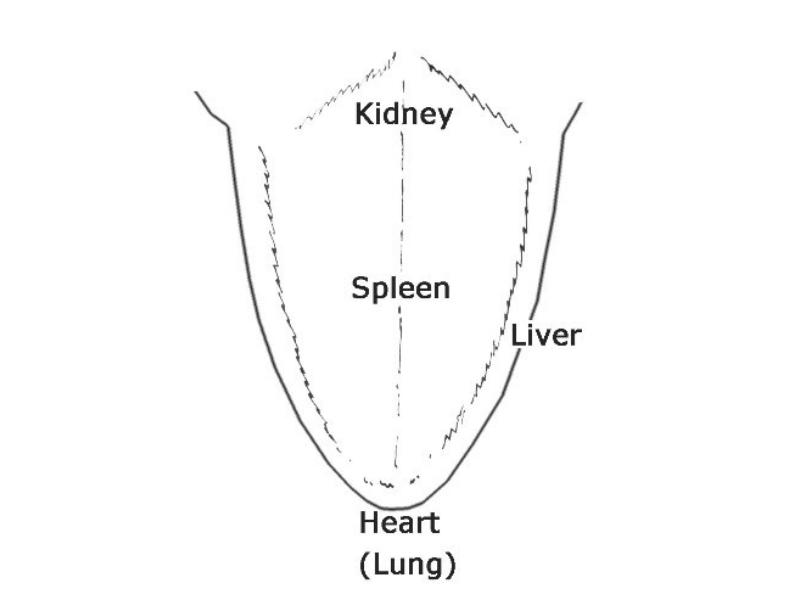

Areas of the Tongue

Some correspondence exists between specific areas of the tongue and the state of the bowels and viscera. Although this has been a subject of debate, some correspondences are generally agreed on. See the image below.

|

| The tongue with main correspondences to the viscera |

|---|

Agreed Theories

The following three correspondences are generally accepted.

Root: The root of the tongue is the rear section closest to the throat. It is related to the kidney, which is understood to be the root of the body.

Center: The central area of the tongue’s surface lies between the root and the tip. It reflects the spleen and stomach, which lie in the center burner.

Tip: The tip reflects the condition of the heart.

Controversial Theories

Some texts state that the sides of the tongue reflect the state of the liver and gallbladder and that the tip reflects the lung. In other sources, the left side of the tongue is assigned to the lung and right side to the liver. A few other variations are also found. In view of these inconsistencies, organ correspondences should always be correlated with data from the other examinations.

Inspecting the Shape and Texture of the Tongue Fur

Healthy people have a thin coating of fur on the tongue. This is attributed to the upward steaming of stomach qì. Textures are categorized as moist or dry, thick, clean or slimy and grimy. Shapes change when the fur peels.

Moist and Dry Tongue Furs

A healthy tongue is kept naturally moist by saliva (drool and spittle).

Basic types

- A

moist tongue fur

(苔潤 tāi rùn) is one that is coated in liquid. It is not necessarily pathological. - A

glossy tongue fur

(苔滑 tāi huá) is a very moist tongue fur that is coated in drool that almost drips when the tongue is extended. It indicates damp phlegm or cold-damp. - A

dry tongue fur

(苔燥 tāi zào) is one that is drier than normal. It usually means heat. Atongue fur with little liquid

is the same in meaning. - A

(糙苔 cāo tāi) is one that is rough to the touch, in severe cases feeling like sand. It feels dry, rough, and even prickly to the touch, although with experience these qualities can be judged by inspection. It usually indicates exuberant heat, but it may also be seen in center phlegm-damp obstruction when this prevents fluids from reaching the upper body. In such cases the dryness is less severe, some degree of sliminess is present, and the patient experiences thirst without desire to drink.coarse (or rough) tongue fur - A

dry fissured tongue fur

(燥裂苔 zào liè tāi) is one that is dry and developing furrows. Slimy tongue fur

is discussed further ahead.

Significance: The moistness or dryness of the tongue fur reflects the state of the fluids. Generally, heat causes the tongue fur to become dry, while water-damp gives rise to a moist fur. However, there are exceptions, notably moistness in provisioning-blood patterns and dryness in dampness patterns.

- A dry fur on a red tongue is normally attributable to severe heat damaging liquid.

- If in febrile disease the tongue fur is still moist, this means that the fluids have not been damaged.

- A moist tongue fur becoming dry means that heat is beginning to damage liquid.

- A dry tongue fur that becomes moist means that heat is abating and liquid is returning.

- A moist tongue that is red or crimson is a sign of heat entering provisioning-blood and suddenly causing liquid to steam upward. The tongue color takes precedence over the tongue fur.

- A pale tongue with glossy fur indicates water-damp collecting internally.

- A dry fur on a pale tongue means dampness obstructing yáng qì. Usually, dampness is reflected in a moist tongue fur. However, when it obstructs yáng qì and prevents fluids being borne up to the mouth, the tongue fur may be dry.

- A glossy white fur with signs such as cold limbs and puffy swelling indicate

yáng vacuity water flood.

- A slimy glossy tongue fur together with spleen stomach signs, such as oppression in the stomach duct, nausea, and sloppy stool, indicates exuberant dampness attributable to spleen vacuity. See below for slimy tongue fur.

Thick and Thin Tongue Furs (苔厚 tāi hòu, 苔薄 tāi bó)

A thin tongue fur

fur is one that allows the underlying tongue surfaces to show through faintly, whereas a thick tongue fur

is one that blots out the tongue surface completely. The thickness of the tongue fur is an index of the exuberance of evil. Thickening and thinning reflect the progression and regression of disease.

A thin tongue fur is attributable to the upward steaming of stomach qì, carrying stomach liquid upward. It is not necessarily pathological. A thick tongue fur arises when food turbidity, phlegm-damp, and disease evils are carried upward by the steaming of stomach qì so that they accumulate on the tongue.

Modern research shows that the thickness of the tongue fur stands in direct relation to the length of the filiform papillae. The longer the filiform papillae, the thicker the fur.

- The thinness and thickness of the tongue fur can help to determine the degree of penetration of evil qì.

- An evenly distributed thin tongue fur occurs in healthy people or at the onset of disease.

- A thick tongue fur occurs in cases of abiding food (persistent food accumulation) or of phlegm turbidity. It signifies disease in the interior and a relatively severe condition.

- A tongue fur that gradually thickens means that an exuberant evil is advancing or that a hidden evil is starting to become apparent.

- A thick tongue fur that gradually grows thinner indicates that right qì is prevailing and the evil is abating or that an internal evil is dispersing outward.

Clean, Slimy, Grimy, and Tofu Tongue Furs

In clinical practice, slimy, grimy, and tofu tongue furs help to determine the state of yáng qì and the presence of damp turbidity.

- A

clean tongue fur

(淨苔 jìng tāi) is a thin fur characterized by a grainy appearance. It is a sign of health. - A

slimy tongue fur

(苔膩 tāi nì) is a thick fur appearing as a layer of mucus over the tongue. It is composed of fine granules, but these may be barely visible, and the tongue body does not usually show through clearly. It is thicker in the middle than at the edges and is not easily scraped off. A slimy tongue fur arises when dampness, phlegm, rheum, or food accumulation obstructs yáng qì. The larger the area of the tongue covered by a slimy fur, the more severe these conditions are. If it covers only the center or the root, it indicates a chronic condition in which the evil resists transformation. - A

grimy tongue fur

(苔垢 tāi gòu) is slimy and dirty-looking. Hence, it is often called agrimy slimy tongue fur

orturbid slimy tongue fur.

It indicates the presence of turbid evils such as damp turbidity and phlegm turbidity or stomach qì vacuity. In stomach qì vacuity, attention must be paid to safeguarding stomach qì when dispelling the evil. - A

tofu tongue fur

(腐苔 fǔ tāi) is a loose fur with large granules. It is thick at the edges and in the middle. It is easily scraped off. The tongue body usually shows through. A tofu tongue fur means debilitation of stomach qì with phlegm turbidity welling upward. It is mostly seen in food accumulation, enduring phlegm turbidity patterns, and in conditions of major damage to stomach qì. It is also seen in internal welling-abscesses of the lung, stomach, or liver and inlower-body gān .

(糜点 mí diǎn) like grains of cooked rice on a smooth bare tongue that can be wiped off but return immediately indicate severe damage to the stomach in seriously ill patients. In the worst cases, when putrefaction speckles spread to other parts of the oral cavity, the condition is termedPutrefaction speckles oral putrefaction

(口糜 kǒu mí).

Peeling Fur (剝苔 bō tāi)

A peeling fur is one that is patchy and interspersed with smooth furless areas. It is attributed to a lack of stomach qì preventing normal upward steaming or desiccation of stomach yīn that leaves no fluid to ascend to the mouth.

- A peeling fur indicates insufficiency of yīn humor and stomach qì vacuity.

- The peeling of a persistent slimy fur indicates a complex condition of phlegm-damp failing to transform with damage to yīn humor and stomach qì.

- A progressively peeling tongue indicates a worsening condition, whereas a peeled tongue fur that gradually gives way to a normal thin white fur indicates a return to health.

- A thick slimy fur that suddenly completely peels away indicates major damage to right qì.

- A tongue completely stripped of fur is called a

smooth bare tongue

ormirror tongue

; it is a critical sign of both desiccation of stomach yīn and damage to stomach qì.

Inspecting the Tongue Fur Color

The normal color of the tongue fur is white. The color may change to yellow or grayish-black under certain circumstances.

White Tongue Fur (苔白 tāi baí)

A white tongue fur occurs in healthy individuals but also appears in exterior patterns, cold patterns, dampness patterns, and phlegm patterns.

Moist and dry white furs

- A clean moist thin white fur is seen in healthy individuals. It may also appear in illness, indicating that the evil has not yet entered the interior and right qì is undamaged.

- A glossy white tongue fur indicates cold. If thin, it indicates exterior wind-cold or interior cold. If thick, it indicates cold-damp or cold phlegm.

- A dry white fur indicates cold evil transforming into heat. An extremely dry thin white tongue fur indicates insufficiency of fluids.

Thin white furs

- A thin white tongue fur on a pale-red tongue, with aversion to cold, heat effusion, and a floating pulse is a sign of the onset of an exterior pattern.

- A thin white tongue fur on a pale tongue in conjunction with lassitude of spirit and cold limbs usually indicates yáng vacuity with internal cold.

- A thin white dry tongue fur on a red-tipped tongue usually indicates dryness-heat damaging liquid or exuberant heart-lung fire.

Thick white furs

- A thick glossy and slimy white fur indicates phlegm-damp or food turbidity. It is usually accompanied by a slimy sensation in the mouth, oppression in the chest, and torpid intake.

- A thick dry white fur indicates transformation of dampness into dryness.

- A thick

(白如积粉 baí rú jī fěn, referring to a floury or chalky appearance) that cannot be scraped away easily is a sign of external contraction of epidemic qì with exuberant heat toxin in the inner body. It is often seen in scourge epidemics.mealy white tongue fur - A thick slimy white tongue fur on a red or crimson tongue body indicates

dampness trapping hidden heat,

(湿遏热伏 shī è rè fú), which is treated by first transforming the dampness to allow the heat to escape rather than with excessive use of cool agents.

Yellow Tongue Fur (苔黄 tāi huáng)

A yellow fur most often signifies heat but may also indicate interior stagnancy. Because heat patterns vary in severity and may involve different evils, different types of yellow fur are distinguished. In most cases, a yellow tongue fur arises when disease evils enter the interior, transform into heat, and create heat among the bowels and viscera that is carried up to the tongue by the steaming of stomach qì. A yellow fur may be pale yellow, deep yellow, or burnt yellow.

- A pale-yellow tongue fur indicates that the heat is mild; a deep-yellow tongue fur indicates that the heat is severe.

- A thin dry yellow fur indicates damage to liquid by heat evil, which calls for attention to the need to safeguard liquid.

- A

(黄瓣苔 huáng bàn tāi) is a tongue fur that has a fissure down the middle to form two petal-shaped patches. It is seen in repletion heat patterns arising when dryness heat binds in the stomach and intestines.yellow petalled tongue fur - A

mixed white and yellow tongue fur

(舌苔黄白相兼 shé tāi huáng baí xiāng jiān) is one in which there are patches of white and yellow. This indicates the initial-stage transformation of cold into heat, which is associated with evils passing into the interior. A tongue fur turning from white to yellow (舌苔由白转黄 shé tāi yóu baí zhuǎn huáng) has the same significance. - An

old-yellow fur

(老黃苔 lǎo huáng tāi) is dark yellow. Aburnt-yellow tongue fur

(舌苔焦黃 shé tāi jiāo huáng) is a blackish-yellow. Both indicate the gathering of repletion heat andheat bind

(heat binding in the intestines and causing constipation). - A slimy yellow fur usually indicates damp-heat.

- A glossy yellow tongue fur (舌苔黄滑 shé tāi huáng huá) on a pale enlarged tender-soft tongue indicates debilitation of yáng qì and water-damp failing to transform. It is important to take note of this because a yellow tongue fur may reflect interior patterns rather than heat.

Gray and Black Tongue Furs (舌苔灰黑 shé tāi huī hēi)

| Turbidity |

|---|

Turbidityappears in terms such as food turbidity, damp turbidity,and phlegm turbidity.Severe forms are called foul turbidity.These terms merely emphasize the unclean, polluting nature of food stagnating in the stomach and intestines, dampness, and phlegm. |

A

- A glossy black fur signifies either stomach vacuity or kidney vacuity.

- A thick slimy black fur usually indicates a phlegm-damp complication.

- A parched black fur that is rough and dry and that covers a red or crimson tongue body indicates damp-heat transforming into dryness or damage to yīn by intense heat.

- A slimy yellow tongue covered by a grayish-black film is generally indicative of exuberant damp-heat evil.

- A mixed gray and white fur or a thin slimy glossy gray fur generally indicates cold-damp.

Tongue and Fur Combinations

Pale-white tongue

- with no fur: Yáng debilitation in enduring illness; dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- with a transparent fur: Spleen-stomach vacuity cold.

- with a thin white fur at the margins and none in the middle: Dual vacuity of qì and blood; stomach yīn vacuity.

- with a white fur: Insufficiency of yáng qì; dual vacuity of qì and blood.

- with a slimy white fur: Spleen-stomach vacuity with phlegm-damp gathering.

- with a glossy gray-black fur: Yáng vacuity with internal cold; phlegm-damp collecting internally.

Pale-red tongue

- with a thin white fur: Healthy individuals; wind-cold exterior patterns; mild disease or shallow penetration of evil.

- with a white fur: If only the tip of tongue is red, this means a wind-heat exterior pattern or hyperactive heart fire.

- with a mealy white fur: External contraction of epidemic qì with exuberant heat toxin in the inner body.

- with a white and tofu fur: Phlegm-food collecting internally; debilitation of stomach qì with phlegm turbidity welling upward.

- with a yellow and white mixed fur: Exterior patterns transforming into heat and passing into the interior.

- with a slimy thick white fur: Damp turbidity or phlegm-rheum collecting internally; food accumulating in the stomach and intestines; cold-damp impediment (bì) patterns.

- with a thin yellow fur: Mild interior heat patterns.

- with a dry yellow fur and little liquid: Interior heat damaging liquid and transforming into dryness; desiccated liquid and blood dryness; dryness of the stomach and intestines.

- with a slimy yellow fur: Damp-heat; phlegm-heat; food accumulation transforming into heat.

Bright-red tongue

- with a dry white fur: Evil heat entering the interior and damaging liquid.

- with a floating grimy tongue fur: Depletion of right qì with residual damp-heat.

- with a thick slimy white tongue fur on a red or crimson tongue body indicates

dampness trapping hidden heat.

- with a thin yellow fur with little liquid: Interior heat that has already damaged the fluids.

- with a thick yellow fur with little liquid: Exuberant qì-aspect heat damage to yīn humor.

- with a slimy yellow fur: Damp-heat brewing internally; phlegm and heat biding together.

- with a dry black fur: Desiccated fluid and dry blood.

Crimson tongue

- with a dry burnt-yellow tongue fur: Severe internal heat; heat binding in the stomach and intestines.

- with a dry black fur: Extreme heat damaging yīn.

- with no fur: Heat entering the blood aspect; yīn vacuity with effulgent fire.

Green-blue or purple tongue

- with a dry yellow fur: Extreme heat and desiccated liquid.

- with a dry burnt-black fur: Severe heat toxin with major damage to fluids.

- with a white glossy fur: Yáng vacuity with exuberant cold; congealing and stagnating qì and blood.

Closing Remarks on the Tongue Examination

Inspection of the tongue and fur holds an important place in the four examinations.

The body of the tongue is of greatest significance in judging the strength or right qì. It may also provide an indication of the severity of the condition, as in the case of a pale tongue, which indicates qì and blood vacuity, or a crimson tongue, which indicates yīn vacuity or the penetration of evil heat to the provisioning aspect.

The tongue fur, though primarily an indicator of the severity of an illness is sometimes a useful measure of the strength of right qì. This is true in the case of a thick slimy fur, which indicates exuberant damp turbidity, or a peeling fur, which indicates stomach qì vacuity or damage to yīn humor. The moistness of the tongue fur sheds light on the state of fluids.

For these reasons, the tongue examination is of special importance in externally contracted febrile disease. The Chá Shé Biàn Zhèng Gē (Tongue Inspection and Pattern Identification Songs

) states:

Exterior white, interior yellow,

Decide sweating or precipitation.

Provisioning crimson, defense white,

Refine therapeutic differentiations,

Then check fluid for further information.

Moist, no damage; dry, depletion.