Search in dictionary

Channels and network vessels

经络 〔經絡〕 jīng luò

The main pathways along which qì flows are called

(jīng); smaller branches are called

(luò). The channels and network vessels are the pathways by which qì and blood reach all parts of the body, facilitating communication between the bowels and viscera and all other areas.

There are twelve regular channels

duplicated on either side of the body. Each is associated with a specific bowel (stomach, small intestine, large intestine, bladder, gallbladder, and triple burner) or viscus (liver, heart, spleen, lung, kidney, and pericardium). There are eight other major pathways not associated with specific bowel or viscus, which are known as the the eight extraordinary vessels

; these act as reservoirs for the main twelve channels.

The twelve regular channels are paired in the same way as the bowels and viscera: the heart channel with the small intestine channel, the lung channel with the large intestine channel, and so on. The pericardium channel provides the counterpart of the triple burner channel.

The channels associated with the viscera are called yīn channels, while those associated with the bowels are yáng channels. The yīn channels pass along the inner face of the limbs to the hands or feet. The yáng channels pass along the outer face of the limbs.

Each channel homes to

the bowel or viscus with which it is associated. It also nets

the bowel or viscus paired with the one to which it homes. For example, the heart channel homes to the heart and nets the small intestine channel; the lung channel homes to the lung and nets the large intestine channel, and so forth.

The channel and network vessel system also includes the eight extraordinary vessels, which are not directly associated with specific bowels and viscera.

Specific points on the channels and vessels are used to apply stimuli through needles and moxa. Such stimuli can supplement qì and blood or drain away evils or accumulations of qì or blood.

How Did the Channel System Arise?

The origin of the system of channels and network vessels and of the points at which therapeutic stimuli can be applied is still unclear. Nevertheless, most scholars now agree that we can discern two originally distinct currents, which combined during the Hàn dynasty to form the well-known theoretical and practical concepts first expressed in the Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng.

These two currents can be traced back in early medical manuscript literature such as the Mǎwángduī texts. On the one hand, the early writers recognized some diseases as being caused by the presence of demonic influences. Treatment accordingly consisted of stabbing, whipping, or cauterizing the affected area to exorcise the malign presence, which was most commonly done with peach wood, used for its exorcistic effect. On the other hand, and distinct from this paradigm of treating specific diseases through localized therapy, a literature developed around the concept of cultivating the flow of qì in the body, what we now refer to as qì-gōng, through sexual cultivation, gymnastic exercises, and breath control. The aim of these practices was not the treatment of disease, but the life nurturing (yǎng shēng 养生). This discourse on the movement of qì within the body soon included a conception of channels that were connected in a network and had to be dredged and kept free of obstacles, similar to the river and canal system in early Hàn China.

To this day, many ways in which Chinese medicine is used are arguably rooted in this ingenious combination of point-specific clinical treatment and holistic longevity practices for preventative medicine.

Modern Chinese textbooks suggest that the following clinical observations may have contributed to the mapping of the channel system:

Needle sensation: Needling of points can cause aching, twinging, numbness, and feelings of distension or heaviness, very often along the channel. Hence, needle sensations may have contributed to the plotting of the channel pathways.

Comparison of point indications: We know that points close to each other on each of the channels tend to be used to treat similar problems. For example, points on the lateral aspects of the arms tend to treat pathoconditions of the head and face, while those of the medial aspect of the arm tend to treat throat, chest, and lung pathoconditions. Observations of this kind may also have contributed to the channel model.

Outward reflections of bowel and visceral diseases: We know that tenderness of the flesh, binding or knotting within the flesh, skin rashes, and changes in the skin complexion at certain points can reflect disease of the bowel or viscus that the channels on which they are located home to.

Observations of this kind may also have contributed.

Scientific Basis?

The channel and network vessel system corresponds to no known entity in modern anatomy. Traditional Chinese medical texts never described the vascular system (blood vessels) in detail, and the channels and network vessel system does not resemble it at all. Considerable scientific research has been done, but the findings do not suggest a cohesive picture.

Some studies have revealed the existence of biological processes that may have stimulated traditional descriptions of the channel and network system. Most studies on acupuncture have assumed that needling produces its effects by stimulating the nervous system and, in particular, the production of endorphins, naturally occurring pain-killing molecules. Other research, however, has shown a relationship between the stimulation of acupoints and brain activity, which suggests that what the ancient Chinese identified as the channel system may be explicable in terms of a bioelectrical communication system. At present, however, no explanation is universally accepted.

Components

The channel and network vessel system is composed of two main parts: the twelve regular channels and the eight extraordinary vessels. Both are the pathways whereby qì and blood are supplied to all parts of the body. It is by the channel system that the viscera communicate with each other and with their corresponding bowels, orifices, and body constituents.

In addition, there are twelve channel sinews and twelve cutaneous regions, which are related to the twelve regular channels.

Channels and Network Vesselsor Meridians and Collaterals, Warp and Woof |

|---|

All translations are substantiated. The Chinese term is a two-character combination that has only ever been used to denote the pathways of qì in the body. So, to understand the origin of the term, it is important to be aware of the early meanings of the two component characters. 经 jīng means warp, meridian line, main line, and络 luò silk threads, a netlike structure such as tangerine pith, or connection. Both 经 and 络 have 纟 mì radical meaning silk and by extension, fine threads. The three translations of the terms (meridians and collaterals, warp and woof, and channels and network vessels) are justified as follows:

channel and network vesselto be the translation that best enables English readers to understand the original medical conception of the system. |

The Twelve Channels

The twelve channels (十二经脉 shí èr jīng mài) are also called the twelve regular channels (十二正经 shí èr zhèng mài) These each run between the abdominothoracic cavity or head and one of the four extremities. They each home to a viscus or a bowel and are designated as yīn or yáng accordingly.

The following list includes the full formal designation and their common English abbreviations.

Three Hand Yīn Channels

- Hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung channel (手太阴肺经 shǒu tài yīn fèi jīng), lung channel, abbreviated to LU in English

- Hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) pericardium channel (手厥阴心包经 shǒu jué yīn xīn bāo jīng), pericardium channel, PC

- Hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) heart channel (手少阴心经 shǒu shào yīn xīn jīng), heart channel, HT

Three Hand Yáng Channels

- Hand yáng brightness (yáng míng) large intestine channel (手阳明大肠经 shǒu yáng míng dà cháng jīng), large intestine channel, LI

- Hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) triple burner channel (手少阳三焦经 shǒu shào yáng sān jiāo jīng), triple burner channel, TB

- Hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine channel (手太阳小肠经 shǒu tài yáng xiǎo cháng jīng), small intestine, SI

Three Foot Yīn Channels

- Foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen channel (足太阴脾经 zú tài yīn pí jīng), spleen channel, SP

- Foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) liver channel (足厥阴肝经 zú jué yīn gān jīng), liver channel, LR

- Foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) kidney channel (足少阴肾经 zú shào yīn shèn jīng), kidney channel, KI

Three Foot Yáng Channels

- Foot yáng brightness (yáng míng) stomach channel (足阳明胃经 zú yáng míng wèi jīng), stomach channel, ST

- Foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder channel (足少阳胆经 zú shào yáng dǎn jīng), gallbladder channel, GB

- Foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder channel (足太阳膀胱经 zú tài yáng páng guāng jīng), bladder channel, BL

Chinese medicine recognizes twelve regular channels, each associated with a viscus or bowel and passing along a limb. The Líng Shū (Chapter 33) states, The twelve channel vessels internally home to bowels or viscera and externally nets the limbs and joints

(夫十二经脉者, 内属于府藏, 外络于肢节 fū shí èr jīng mài zhě, nèi shǔ yú fǔ zàng, wài luò yú zhī jié).

Each of the twelve channels is duplicated on either side of the body. Each traverses an inner or outer face of a limb. Inside the body, each channel homes

to one of the twelve internal organs, the yīn channels to the viscera and the yáng channels to the bowels. It then nets

its exterior-interior paired organ. For example, the hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) channel homes to the heart and nets the small intestine, while the hand greater yáng (tài yáng) channel homes to the small intestine and nets the heart.

Homingand Netting |

|---|

When we say a channel homes(属 shǔ) to a specific bowel or viscus, we mean that it enters the bowel or viscus that it belongs to. When we say a channel nets(络 luò) a specific bowel or viscus, we mean that it loosely enmeshes the bowel or viscus that is paired with the bowel or viscus to which it homes. |

Naming of the Channels

Each channel is known by a name composed of three parts: hand or foot; yīn or yáng, and bowel or viscus.

Viscus /bowel: Six of the twelve channels each home to a viscus; the other six each home to a bowel. Only one channel homes to each viscus or bowel, hence the viscus/bowel part of the channel name is unique.

Hand /foot: The six channels that pass over the lower limbs have the word foot

as part of their name; the six that pass over the upper limbs have hand

in their name. Each inner or outer face of the limbs is traversed by three channels.

Yīn /yáng: According to yīn-yáng theory, the inner faces of the limbs and the ventral aspect of the trunk are yīn, while the outer faces of limbs and the dorsal aspect of the trunk are yáng. The viscera are yīn, while the bowels are yáng.

The six channels that pass over the inner faces of the limbs and the ventral aspect of the trunk and that home to a viscus are labeled as yīn; the six that pass over the outer faces of the limbs and dorsal aspect of the trunk and that home to a bowel are labeled as yáng.

The yīn and yáng channels are each divided into three sub-types. The yīn channels are thus designated as greater yīn (tài yīn), lesser yīn (shào yīn), and reverting yīn (jué yīn). The yáng channels are designated as greater yáng (tài yáng), lesser yáng (shào yáng), and yáng míng (yáng míng). We refer to these six names as yīn-yáng designations.

Two channels share each yīn-yáng designation, one traversing the upper limbs and the other traversing the lower limbs. For example, two channels share the designation greater yīn (tài yīn)

: the hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung channel and foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen channel.

The yīn-yáng designations indicate the strength of yīn and yáng qì. Greater yīn (tài yīn) has the most exuberant yīn qì; lesser yīn (shào yīn) has weaker yīn qì; and reverting yīn (jué yīn) has the weakest yīn qì (reverting to yáng).

As to the yáng channels, there is disagreement. According to one view, yáng míng (yáng míng) has the most exuberant yáng qì, followed by greater yáng (tài yáng), and lesser yáng (shào yáng). According to a second view, yáng míng (yáng míng) lies between greater yáng (tài yáng) and lesser yáng (shào yáng).

| The Twelve Regular Channels | |

|---|---|

| Yīn Channels | Yáng Channels |

| Greater yīn (tài yīn) (tài yīn 太阴) | Greater yáng (tài yáng) (tài yáng 太阳) |

| Hand greater yīn (tài yīn) LU channel | Hand greater yáng (tài yáng) SI channel |

| Foot greater yīn (tài yīn) SP channel | Foot greater yáng (tài yáng) BL channel |

| Lesser yīn (shào yīn) (shào yīn 少阴) | Lesser yáng (shào yáng) (shào yáng 少阳) |

| Hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) HT channel | Hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) TB channel |

| Foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) KI channel | Foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) GB channel |

| Reverting yīn (jué yīn) (jué yīn 厥阴) | Yáng míng (yáng míng) (yáng míng 阳明) |

| Hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) PC channel | Hand yáng míng (yáng míng) LI channel |

| Foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) LR channel | Foot yáng míng (yáng míng) ST channel |

Note also that in the Nèi Jīng, the reverting yīn (jué yīn) designated as the first yīn [channel],

the lesser yīn (shào yīn) as the second yīn,

and greater yīn (tài yīn) as the third yīn.

Lesser yáng (shào yáng), yáng míng (yáng míng), and greater yáng (tài yáng) are designated as the first, second, and third yáng [channels] respectively. This naming system suggests that (some of) the authors of the Nèi Jīng considered yáng míng (yáng míng) as lying between greater yáng (tài yáng) and lesser yáng (shào yáng).

Because of the disagreement over the strength of qì in the channels, the threefold distinction in the yīn-yáng designation is of dubious significance. It is, however, significant in cold damage theory, where it labels disease of either of the two channels. For example, yáng míng (yáng míng) disease

generically denotes any disorder that affects the hand large intestine and foot stomach channels. In cold damage disease, it is noteworthy that yáng míng (yáng míng) disease manifests in the greatest heat (heat is yáng).

Distribution of the Channels

The twelve channels have external and internal pathways.

- The external pathways are the parts of the channel that run close to the surface and are hence accessible to needles. In the diagrams provided for each of the channel pathways below, the external pathways are marked with a solid line.

- The internal pathways are the sections that lie deep within the abdominothoracic cavity.

Limbs: The yīn channels are on the medial aspects of the limbs, while the yáng channels are on the lateral aspects. The distribution on the limbs is roughly as follows:

- Anterior margin: greater yīn (tài yīn) and yáng míng (yáng míng).

- Midline: reverting yīn (jué yīn) and lesser yáng (shào yáng).

- Posterior margin: lesser yīn (shào yīn) and greater yáng (tài yáng).

This is the general pattern of distribution on both the upper and lower limbs. Nevertheless, the three foot yīn channels differ from a level eight cùn above the ankle downward, where the reverting yīn (jué yīn) is at the front, greater yīn (tài yīn) is in the middle, and lesser yīn (shào yīn) as at the back.

Head: The yáng channels run over the face and forehead. The greater yáng (tài yáng) traverses the face and cheek, the apex, and the back of the head. The lesser yáng (shào yáng) traverses the side of the head.

Trunk.

- The three yáng channels of the hand traverse the shoulder and scapular regions.

- The three hand yīn channels all emerge from the armpit.

- The three yáng channels of the foot follow the pattern of distribution described above, namely that the yáng míng (yáng míng) is toward the front (chest and abdomen), the greater yáng (tài yáng) is most dorsal (close to the spine), and the lesser yáng (shào yáng) traverses the lateral aspect of the trunk.

- The three yīn channels all traverse the ventral aspect of the trunk.

| Channel Distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yīn Channels Homing to the viscera and netting the bowels;traversing the abdomen and inner face of limbs | Yáng Channels Homing to the bowels and netting the viscera; traversing back and outer face of limbs | Position on limbs | |

| Hand | Greater yīn (tài yīn) LU channel | Yáng míng (yáng míng) LI channel | Front |

| Reverting yīn (jué yīn) PC channel | Lesser yáng (shào yáng) TB channel | Middle | |

| Lesser yīn (shào yīn) HT channel | Greater yáng (tài yáng) SI channel | Rear | |

| Foot | Greater yīn (tài yīn) SP channel | Yáng míng (yáng míng) ST channel | Front |

| Reverting yīn (jué yīn) LR channel | Lesser yáng (shào yáng) GB channel | Middle | |

| Lesser yīn (shào yīn) KI channel | Greater yáng (tài yáng) BL channel | Rear | |

Directions and Interconnectedness of Channels

The Líng Shū (Chapter 55) describes the direction of the channels succinctly as follows: The three hand yīn run from viscus to hand; the three hand yáng run from hand to head; the three foot yáng run from head to foot; the three foot yīn run from foot to abdomen.

The three yīn channels of the hand each start in the chest and proceed along the arm to the fingers, where they interconnect with the three yáng channels of the hand with which they stand in exterior-interior relationship.

- Hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung → hand yáng míng (yáng míng) large intestine

- Hand lesser yin heart → hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine

- Hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) pericardium → hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) triple burner

The three yáng channels of the hand each start from the fingertips and proceed up the arms to the head and face, where they interconnect with the three yáng channels of the foot that have the same yīn-yáng designation.

- Hand yáng míng (yáng míng) large intestine → foot yáng míng (yáng míng) stomach

- Hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine → foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder

- Hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) triple burner → foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder

The three yáng channels of the foot each start from the head and face and proceed down to the toes, where they interconnect with the three yīn channels of the foot with which they stand in exterior-interior relationship.

- Foot yáng míng (yáng míng) stomach → foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen

- Foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder → foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) kidney

- Foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder → foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) liver

The three yīn channels of the foot each start from the toes and proceed up the legs to the abdomen and chest (before continuing upward to the head), where they interconnect with the three yīn channels of the hand that have the same yīn-yáng designation.

- Foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen → hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung

- Foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) kidney → hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) heart

- Foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) liver → hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) pericardium

The yīn and yáng channels standing in exterior-interior relationship interconnect at the extremities:

- The hand greater yīn lung channel interconnects with the hand yáng míng (yáng míng) large intestine channel at the tip of the index finger.

- The hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) heart channel interconnects with the hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine channel at the tip of the little finger.

- The hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) pericardium channel interconnects with the hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) triple burner channel at the tip of the middle finger.

- The foot yáng brightness stomach channel interconnects with the foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen channel at the tip of the big toe.

- The foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder channel interconnects with the foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) kidney channel at the little toe.

- The foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder channel interconnects with the foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) liver channel at the tuft of hair close to the toenail of the big toe.

The hand and foot yáng channels of the same yīn-yáng sub-designation interconnect at the head:

- The hand yáng míng (yáng míng) large intestine channel and foot yáng míng (yáng míng) stomach channel interconnect at the side of the nose.

- The hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine channel interconnects with the foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder channel at the inner canthus (the inner corner of the eye).

- The hand lesser yáng (shào yáng) triple burner channel interconnects with the foot lesser yáng (shào yáng) gallbladder channel at the outer canthus.

The hand and foot yīn channels interconnect in the chest.

- The foot greater yīn (tài yīn) spleen channel interconnects with the hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) heart channel in the center of the chest.

- The foot lesser yīn (shào yīn) kidney channel interconnects with the hand reverting yīn (jué yīn) pericardium channel in the chest.

- The foot reverting yīn (jué yīn) liver channel interconnects with the hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung channel in the lung.

Exterior-interior relationships

Like the bowels and viscera to which they belong, the channels form exterior-interior pairs. Yīn channels are interior, while yáng channels are exterior. Although all twelve regular channels have pathways in the body ' s surface and in the body’s interior, they are designated as interior

or exterior

depending on whether they home to a viscus (interior) or a bowel (exterior).

Channels that stand in exterior-interior relationship with each other interconnect at the extremities. In the interior, they each home to their respective viscus or bowel, as well as netting

the viscus or bowel of the channel with which they each stand in exterior-interior relationship. Thus, the hand greater yáng (tài yáng) small intestine channel homes to the small intestine and nets the heart, while the lesser yīn (shào yīn) heart channel homes to the heart and nets the small intestine.

Furthermore, the channel divergences and divergent network vessels provide further connections.

The exterior-interior relationship between the channels is utilized in therapy. Disease of one channel can be treated by needling points on the exterior-interior corresponding channel. For example, disease of the lung or lung channel can be treated by needling points on the large intestine channel.

The Sequence of Channels

Qì and blood enter the channel system in the center burner and then flow from one channel to another, circulating endlessly, as shown in the diagram.

|

| Channel sequence |

|---|

Notes on Pathway Descriptions and Channel Points

The descriptions of the pathways that follow are based on the original text of the Nèi Jīng but are expressed in terms of modern anatomy. In the overviews of the channel pathways, the main external pathway of the channels, on which acupoints are located, are underlined. The description of the channel pathways is followed by examples of major commonly used acupoints belonging to channels. The information for each point includes location, type of stimulus commonly applied and the angle of the needle insertion, as well as categories to which the point belongs.

The Eight Extraordinary Vessels

The eight extraordinary vessels (奇经八脉 qí jīng bā mài): These are often described as reservoirs for the twelve regular channels.

Governing vessel (GV, 督脉 dū mài)Controlling vessel (CV, 任脉 rèn mài)Thoroughfare vessel (TV, 冲脉 chōng mài)Girdling vessel (GIR, 带脉 dài mài)Yīn and yáng springing vessels (YIS, YAS, 阴/阳跷脉 yīn/yáng qiāo mài)Yīn and yáng linking vessels (YIL, YAL, 阴/阳维脉 yīn/yáng wéi mài)

Only the governing (dū) and controlling vessels (rèn) have their own acupoints, while the other vessels share acupoints with regular channels.

The twelve regular vessels together with the governing (dū) and controlling (rèn) vessels are collectively known as the fourteen channel vessels

(十四经脉 shí sì jīng mài). Note that the terms channel

and vessel

overlap in meaning. Any channel may be referred to as a channel vessel..

Other Large Components

Other components of the channel and network system include the channel divergences, network vessels, channel sinews, and cutaneous regions.

- The larger ones are the

divergent network vessels

(別絡 bié luò), which have charted pathways. - The smaller network vessels include the

(浮络 fú luò), which supply qì and blood to the body ' s surface, andsuperficial network vessels

(孙络 sūn luò), which are the smallest of all network vessels. These are not charted.grandchild network vessels

twelve channel sinews.

Acupoints

Acupuncture points, also called acupoints or simply points, are sites on the body, mostly located on the channels and vessels, where the qì flow in the body is most easily detected and manipulated.

Palpable changes at certain acupoints can provide diagnostic information.

Insertion of needles or application of moxibustion at most acupuncture points allows the adjustment of qì flow that has therapeutic effects. Therapeutic stimulus at different points produces different effects. Combinations of points are often chosen.

Most acupoints are located on the channels and vessels, but there are also a limited number of nonchannel points. Only two of the eight extraordinary vessels have their own points, while the others only share points on specific channels.

Many channel points fall into specific categories that have special indications in treatment.

Styles of acupuncture vary greatly, but certain points are generally considered to be more reactive than others. In the description of the channels and vessels below, the major points on each are briefly discussed.

Naming of Points

Acupuncture points are also called acupoints

or simply points

in English. In Chinese, they are called 腧穴 shù xuè or 穴道 xué dào, or simply 穴 xué. The word 穴 xué means a hole

or cave,

reflecting the fact that they are largely located at soft points in the flesh between sinews and bones.

In English, acupoints are usually labeled by the channel on which they are located and by sequence number: KI-1, KI-2, KI-3. We call these designations alphanumeric codes.

In Chinese, by contrast, they have unique names such 涌泉 yǒng quán, Gushing Spring,

然谷 rán gǔ, Blazing Valley,

太溪 tài xī, Great Ravine.

Many of these names are metaphors reflecting the conception of the whole body as the territory of a vast empire with mountains, valley, streams, rivers, and roads. In this text, wherever convenient, we give not only the alphanumeric name for each point but also the Pīnyīn name and translation, and often the Chinese name as well: KI-1 (涌泉 yǒng quán, Gushing Spring), KI-2 (然谷 rán gǔ, Blazing Valley), 太溪 tài xī, KI-3 (Great Ravine).

Distribution of Points

Most points are located on the channels. However, many non-channel points have been discovered through clinical experience over the centuries. These cannot be inserted into the traditional theory of the channels and network vessels but are nevertheless efficacious in therapy.

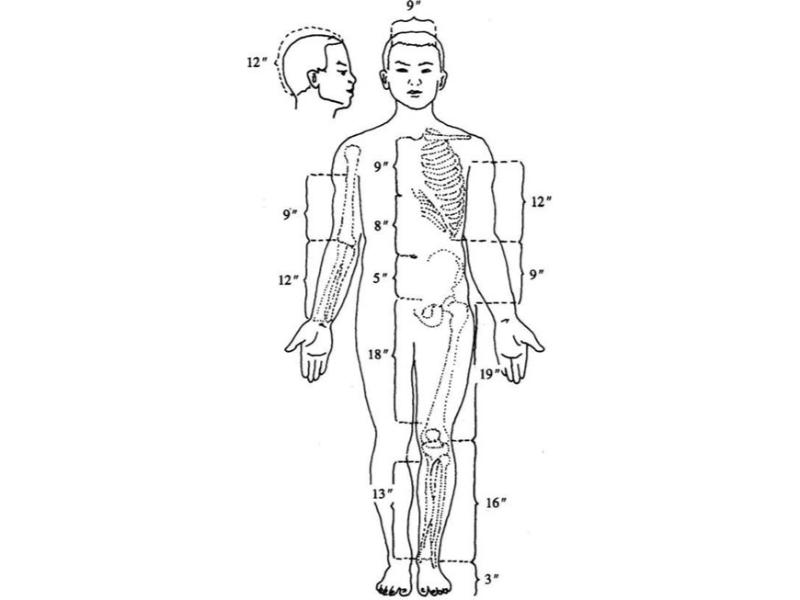

Point Locations

Point locations are described in terms of distance and direction from natural landmarks on the body ' s surface. The measuring system uses the proportional units of bone divisions and cùn

(or body inch

).

Anatomical landmarks (体表解剖标志 jiě pōu biāo zhì): Landmarks are fixed or moving. Fixed landmarks include the nose, eyes, lips tongue, and ears (the five offices

), the fingernails, nipples, and umbilicus. Moving landmarks include skin creases at joints, and depressions in the flesh, and prominent sinews.

Cùn (寸 cùn), body inch: Acupoints are often located in terms of the number of cùn from a particular anatomical landmark or from other points. The cùn, which is divided into 10 fēn (分 fēn), is not a fixed unit of measure but is relative to the patient’s body size. The breadth of index and middle finger is 1.5 cùn (1 cùn and 5 fēn), and the breadth of the four fingers is figured as 3 cùn. Practitioners can use their own figures as a rough guide, but this has to be adjusted when applied to patients with larger or smaller bodies.

|

| Bone standard |

|---|

The cùn varies in size according to the section of the body that is being measured. For example, the distance between the two nipples is eight cùn and the distance between the two corners of the hairline is nine cùn. It is clear from this that the cùn used as the horizontal measure of the forehead are considerably smaller than those used as the horizontal measure of the chest.

Bone standard (骨度 gǔ dù): This is a scheme of correspondences between the cùn and the size of bones.

| Bone Standard | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Body part | From … to …. | Cùn | Area applied |

| Head and Neck | Anterior hairline to posterior hairline | 12 | Forehead and nape |

| Anterior hairline to acupoint between eyebrows (Hall of Impression) | 3 | ||

| Posterior hairline to T7 | 3 | ||

| From one mastoid process (completion bone) to other | 9 | Horizontally between points of head | |

| From one frontal angle (ST-8) to other | 9 | ||

| Chest and Abdomen | Xiphoid process to umbilicus | 8 | Upper abdomen |

| Umbilicus to pubic bone (transverse bone) | 5 | Lower abdomen | |

| Armpit to 11the rib | 12 | Rib-side | |

| Nipple to nipple | 8 | Chest and abdomen | |

| Clavicle to clavicle | 8 | Chest and abdomen in women | |

| Upper Limbs | Anterior crease of armpit to elbow crease | 9 | Upper arm |

| Elbow crease to wrist crease | 12 | Forearm | |

| Lower Limbs | Upper horizonal edge of pubic bone to medial epicondyle of femur | 18 | Inner face of thigh |

| Ball of femur to lower extremity of kneecap | 19 | Outer surface of thigh | |

| Lower gluteal crease (BL-36) to center of popliteal crease | 15 | Back of thigh | |

| Below external epicondyle of tibia (SP-9) to inner ankle bone | 13 | Medial aspect of lower leg | |

| Lower extremity of kneecap to outer ankle bone | 16 | Lateral face of lower leg | |

Point Categories

Many acupuncture points belong to one or more special categories, each of which is distinguished by specific therapeutic actions and special relationships with the channels and network vessels. The most commonly employed are listed below. See point selection for more details.

Back transport points (背俞穴 bèi shù xué) are located on the foot greater yáng (tài yáng) bladder channel, 1.5 cùn lateral to the spine. They each have a strong therapeutic effect on the bowel or viscus after which they are named.

The five transport points (五输穴 wǔ shū xué) are five points located below the elbows and knees on each of the twelve regular channels. These are, from the extremities, the well (jǐng) points, spring (yíng) points, stream (shù) points, channel (jīng) points (also called river points

in English), and uniting (hé) points (also called sea points

). The qì flow gradually becomes deeper through these points, being much deeper at the uniting points than at the well points.

Source points (原穴 yuán xué) are points on each of the twelve regular channels where the source qì resides. They coincide with the stream (shù) points among the five transport points.

Network points (络穴 luò xué) are points on the twelve regular channels and the governing and controlling vessels at which a network vessel springs from the channel or vessel pathway.

Cleft points (郄穴 xī xué) are points located at depressions in the body’s surface at which signs of vacuity or repletion can be observed.

Lower uniting points (下合穴 xià hé xué) are points on the three yáng channels of the foot where the qì of these channels meets with the qì of the three yáng channels of the hand.

Four command points (四总穴 sì zǒng xué) are four special points used to treat certain areas.

Alarm points (募穴 mù xué, literally mustering points

) are points on the chest and abdomen where channel qì collects. Changes at the points such as swellings or depressions indicate morbidity. Stimulation of the alarm points of the bowels is frequently used clinically to treat disease of the bowels.

Intersection points (交会穴 jiāo huì xué) are points at which two or more channels intersect. Stimulus at such points can affect both channels.

Confluence points of the eight vessels (八脉交会穴 bā mài jiāo huì xué) are points located on the four limbs that are effective in treating disorders associated with the eight extraordinary vessels.

Eight meeting points (百会穴 bā huì xué) are points that each have a powerful therapeutic effect on one of the following: viscera, bowels, qì, blood, sinews, marrow, bones, and vessels.

Thirteen ghost points (十三鬼穴 shí sān guǐ xué): This is a group of points that originated with the Táng dynasty physician Sūn Sī-Miǎo’s method for treating conditions such as mania, withdrawal, and epilepsy, which were once understood to be caused by ghosts or demons. These points are located on the twelve regular channels and the eight extraordinary vessels. In Chinese, the ghost points have special names other than those normally used. For example, SP-1 is normally called yǐn baí, Hidden White, but as a ghost point, it is referred to as guǐ yǎn, Ghost Eye.

Huà Tuó’s paravertebral points (华陀夹脊穴 huà tuó jiā jǐ xué): These are points named after the legendary Chinese physician, who probably lived between 145–208 CE. They are situated along both sides of the spine about 0.5 cùn lateral to the lower end of the spinous process of each vertebra. Their functions are similar to the functions of the governing (dū) vessel and the back transport (bèi shù) points between which they are located.

Nine needles for returning yáng (回阳九针 huí yáng jiǔ zhēn): These points are GV-15, PC-8, SP-6, KI-1, KI-3, CV-12, GB-30, ST-36, and LI-4. They are used to treat yáng collapse, which manifests in reversal cold of the extremities, aversion to cold, green-blue lips, somber-white facial complexion, and a faint pulse on the verge of expiration.

Ā-shì points, or That’s it!

or Oh, yes!

points. These acupoints are most often used to treat disorders in their immediate vicinity but can also treat problems distant from the point. Ā-shì points are not necessarily located on channels. Because their locations vary and reflect the illness and its relationship to the patient, these points are inherently unchartable.

Nonchannel points (经外奇穴 jīng wài qí xué): These are points that are not located on the channels or vessels. They are named in English by alphanumeric codes indicating the parts of the body on which they are located, e.g., M-HN-9, where HN means head and neck; M-BW-1, where BW means back and waist (i.e., back and lumbus); M-CA-18, where CA means chest and abdomen.

Pathology

Disease of the Channels

Since the channel and network vessel system permeates the whole body, all morbid states of the human body can be understood as channel and network vessel pathologies. Any disease affects the flow of qì and blood, and disturbances in the flow of qì and blood manifest in localized signs.

Any morbid state located in an area traversed by a specific channel can be considered a disease of that channel. Since the bowels and viscera are all traversed by channels, their pathologies, as well as those of their related body constituents and orifices, can be seen as channel and network vessel diseases. For example, any morbidity appearing on the pathway of the hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung channel or any pathology of the lung itself or of the skin and body hair or the nose can be regarded as being a disease of the hand greater yīn (tài yīn) lung channel.

Disease among the bowels and viscera can affect different parts of the body through the channels system. For example, in liver fire flaming upward, the liver fire ascends along the channel to affect the head and eyes.

Some diseases affect, or can affect, the channels without affecting the bowels and viscera. Deviation of the eyes and mouth (often referred to in biomedicine as facial paralysis

or Bell’s palsy

) is explained in terms of wind entering the channels. Impediment is a disease that arises when wind, cold, and dampness combine and obstruct the channels, causing pain in the joints or flesh.

Cold Damage Theory

The Shāng Hán Lùn (On Cold Damage

) by the Hàn Dynasty physician Zhāng Jī (Zhāng Zhòng-Jǐng) presents a systematized description of externally contracted febrile disease that details progression of disease through the channels. In this theory, externally contracted disease is called cold damage,

because cold evil is understood to be the main cause.

Cold damage theory posits that external evils such as wind and cold enter through the exterior, usually affecting the greater yáng (tài yáng) channel first. The evils may then pass from the greater yáng (tài yáng) to other channels. The disease of each channel manifests in specific signs and patterns. By convention, channel names are used to label the various conditions, although scholars generally agree that they denote stages of development rather than the channels themselves.

Therapeutic Effects Produced by Stimulus

The channels and network vessels are the main focus of acupuncture and moxibustion (acumoxatherapy). The practitioner inserts needles or applies moxibustion at acupuncture points to adjust the flow of qì in the channels and network vessels and thereby bring about specific therapeutic effects. Tuī-ná and cupping also apply channel theory. In medicinal therapy, each medicinal is understood to produce therapeutic effects on one or more channels.

In acumoxatherapy, needle or moxa stimulus at any given point can produce a local or remote therapeutic effect. See acumoxatherapy.

Local Effect

All points can be stimulated to produce therapeutic effects on the local channel pathway and adjacent areas. For example, BL-1 (jīng míng, Bright Eyes), ST-1 (chéng qì, Tear Container), and ST-2 (sì baí, Four Whites) are points close to the eyes that are commonly used to treat eye diseases.

Remote Effect

Many of the points of the fourteen channels can be used to produce a therapeutic stimulus at a remote area on the same channel or even on a different channel. Notably, the points distal to the elbows and knees on the twelve regular channels, in addition to being used for local problems, are particularly able to treat disorders of the bowels and viscera. For example, LI-4 (hé gǔ, Valley Union) treats not only wrist problems but also problems of the head, neck, and face, as well as heat effusion (fever). ST-36 (zú sān lǐ, Leg Three Lǐ) treats not only problems of the lower limbs but also digestive disorders, as well as enhancing right qì.

Specific Effects

The effects that can be produced by stimulating points are not entirely explicable in terms of local and remote effects. A point can have an action that is entirely different from that of a point close to it. For example, GV-14 (dà zhuī, Great Hammer) is especially effective for abating heat effusion, while BL-67 (zhì yīn, Reaching Yīn) can correct the position of the fetus.

In addition, certain points have a two-way action. For instance, ST-25 (tiān shū, Celestial Pivot) treats not only diarrhea but also constipation.

Finally, certain specific effects can be elicited by stimulating points that belong to point categories. See point selection.

Back to search result Previous Next