Search in dictionary

Pulse examination

脉诊 〔脈診〕 mài zhěn

Also pulse-taking. Palpation of blood vessels in specific areas of the body to judge the state of qì and blood and the bowels and viscera and to assess whether the condition of the patient and determine whether it is improving or deteriorating.

There are several places where a pulse can be felt, such as the wrist, neck, groin, and foot. Up until the Hàn Dynasty, the pulse was commonly taken at three positions on the body: Man’s Prognosis (on the external carotid artery of the neck), the wrist pulse (by the styloid process of the radius), and the instep yáng (on the dorsal pedis artery). In modern clinical practice, the first and third positions are rarely used; usually, only the wrist pulse located at the radial styloid process is felt.

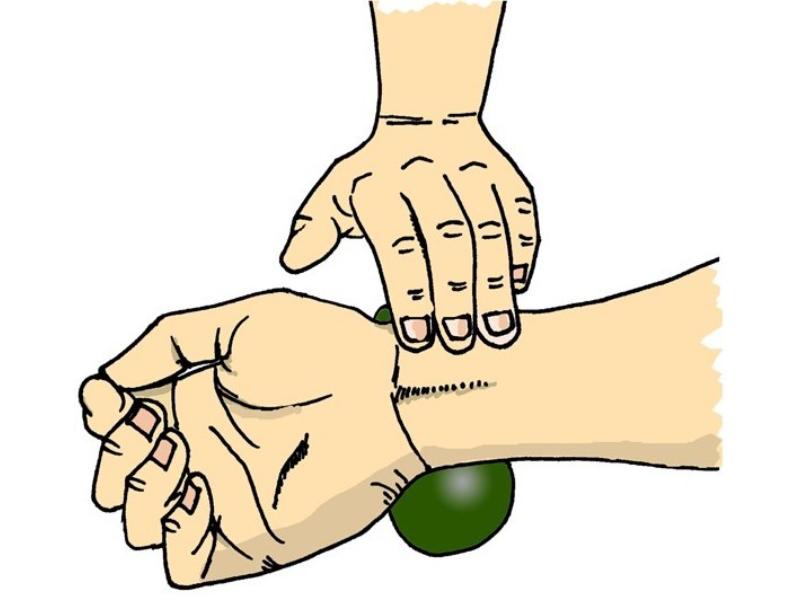

The wrist pulse is usually felt with index, middle, and third fingers, which touch the inch (寸 cùn), bar (关 guān), and cubit (尺 chǐ) positions respectively, as shown in the image below. The wrist pulse is often referred to as the inch opening

(寸口 cùn kǒu) pulse. Here, inch

refers to the position closest to the patient’s hand, while opening

refers to the surfacing of the blood vessel at this point, making it open to examination.

The depth, speed, force, breadth, fluency, tension, and regularity of the pulse provide information about the state of right qì, the location of the illness, and its nature. For example, a floating pulse is associated with the exterior, while a sunken pulse is associated with the interior. A rapid pulse indicates heat, while a slow pulse indicates cold.

Contents

- Pulse-Taking Method

- The Normal Pulse and Its Variations

- Morbid Pulses

- Pulse Combinations

- Inquiry about Diet and Taste in the Mouth

- The Seven Strange Pulses

- Women’s Pulses

- Infants’ and Children’s Pulses

- Significance of the Pulse

- Congruence and Incongruence of Pulse and Signs

Pulse-Taking Method

The pulse examination is conducted as follows:

|

| Hand positions for taking the pulse |

|---|

The pulse should be taken at calm dawn.

Calm dawn(平旦 píng dàn) is the two-hour period of the traditional Chinese clock to 3–5 a.m. At this time, the pulse is least subject to external influences. Usually, the best a practitioner can do is take the pulse in as quiet and relaxed an atmosphere as possible so that external and emotional factors will cause minimum distortion of the patient’s pulse. The pulse should be felt for at least one or two minutes in order to ensure maximum accuracy.

Position: The radial pulse is located on the inner side (the paler side) of the arm close to the wrist, and right next to the styloid process of the radius. The pulse-taking area is divided into three positions: inch (寸 cùn), bar (关 guān), and cubit (尺 chǐ). When the person taking the pulse puts their index, middle, and ring fingers together and places them on the pulse area, the tips of the finger match the inch, bar, and cubit positions. The fingertips sit in the depression between the radius and a tendon.

Since the pulse is taken on both wrists, there are six points in all that the fingers touch. These are called the six pulses.

According to classical literature, the condition of each of the bowels and viscera is reflected in the six pulses. The correspondences are as follows:

- Right inch: lung. Left inch: heart.

- Right bar: stomach and spleen. Left bar: liver and gallbladder.

- Right and left cubit: kidney.

Over the centuries, other schemes of correspondence have been postulated, as the table below shows.

| Correspondence of Pulse Positions to Bowels and Viscera in the Classics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Nàn Jīng Classic of Difficult Issues | Mài Jīng Pulse Classic | Jǐng Yè Quán Shū Jǐng-Yuè’s Complete Compendium | Yī zōng jīn jiàn Golden Mirror | |

| Inch (cùn) | Left | HT; SI | HT; SI | HT; PC | HT; chest center |

| Right | LU; LI | LU; LI | LU; chest center | LU; interior of the chest | Bar (guān) | Left | LR; GB | LR; GB | LR; GB | LR; diaphragm; GB |

| Right | SP; ST | SP; ST | SP; ST | SP; ST | Cubit (chǐ) | Left | KI; BL | KI; BL | KI; BL; LI | KI; BL; SI |

| Right | KI; life gate | KI; TB | KI; TB; life gate; SI | KI; LI | |

Note: Chest centerrefers to the anterior chest between the nipples. Interior of the chestrefers to the thoracic cavity. | |||||

Posture: The patient should be either seated upright or lying supine. Their forearm should be in a horizontal position level with their heart. The palm of the hand should be facing upward. The wrist should be resting on a soft pad and kept straight and relaxed. Incorrect posture may affect the flow of qì and blood and therefore falsify the pulse.

Normal breathing: The practitioner should ensure that her own breathing is natural and even. This ensures maximum accuracy when gauging the speed of the pulse. It also helps the mind to be fully focused and hence be able to detect even the slightest changes.

Feeling the pulse: The practitioner places the index finger on the inch point, which is closest to the hand. She then allows her middle and fourth (ring) finger to rest on the bar and cubit points, respectively. The following points should be noted.

- Spacing: The spacing of the three fingers used in taking the pulse should depend on the height of the patient. Withtall patients, the fingers should be spaced slightly apart. Withshort patients, they should be kept close together. With infants, the use of only one finger may be necessary.

- Tips only: Use only the very tips of the fingers and apply even pressure with all three fingers. This helps to ensure accuracy.

- Levels: Varying the amount of pressure applied allows differences in the pulse at different levels to be detected. There are three pressure levels. The superficial level is felt by applying a light touch. The deep level is felt by pressing firmly. The mid-level is between them. Sometimes, the position of the fingers must be adjusted to feel all three levels.

- Three fingers or one: Simultaneous palpation with all three fingers is the norm. However, sometimes a clear picture of the patient’s condition can be gained by apply the fingers individually at the three points.

Judging the pulse: The practitioner is said to have found

the pulse when the pulsation is felt distinctly. She then focuses on the different aspects of the pulse condition. Taking the pulse involves counting the number of beats and identifying a form and pattern.

The speed is measured by counting the number of beats of the patient’s pulse occurring in one complete respiration (one inhalation and one exhalation).

The quality is judged by the depth, speed, force, breadth, fluency, tension, and regularity of the beat. For example, floating and sunken describe the depth; slow and rapid describe the speed; surging and fine describe the breadth of the pulse. Slippery and rough pulses describe the fluency. Stringlike, tight, and soggy describe the tension.

It is important to bear in mind that each quality represents only one aspect of a given pulse condition. Any pulse condition is marked by combinations of qualities. In most cases, a patient’s pulse is described by several qualities, such as floating, slippery, and rapid

or sunken, stringlike, and fine.

Below we present the most common pulse types and their clinical significance. A comparative analysis of similar pulses is given where confusion easily arises. Some of the rarer pulses are mentioned in the comparative analysis rather than under separate headings.

The Normal Pulse and Its Variations

Normal pulse (常脈 cháng mài): with approximately four beats per respiration, or 72–80 beats per minute, the normal pulse is steady and even. It possesses three qualities that may be lacking in unhealthy pulses.

- Spirit: The normal pulse is smooth, gentle, and forceful, indicating

presence of spirit,

that is, general vitality. - Stomach: The normal pulse is equally detectable at the deep and superficial levels, that is, it is neither sunken nor floating. It is neither slow nor rapid, but gentle and even. This indicates the

presence of stomach,

that is, good spleen and stomach health. - Root: The normal pulse is forceful at the deep level, which indicates the

presence of root,

that is, strong qì of the bowels and viscera, especially the kidney. The deep level of the pulse and the cubit pulse reflect the state of the kidney. So, the presence of root is marked by a forceful pulse particularly at the deep level of the cubit pulse. This indicates that even though the patient may be severely ill, the earlier heaven root has not expired.

Variations: The normal pulse may be affected by such factors as age, sex, build, and constitution.

- Infants and children tend to have soft and rapid pulses. Infants have a pulse with 120–140 beats a minute. Children of five or six years old have a pulse of 90–110 beats per minute. As the child matures, the pulse becomes slower and gentler. People in the prime of life have a forceful pulse. The elderly, with weaker qì, blood, and essence, tend to have weaker pulses.

- Women have a slightly softer and more rapid pulse than men.

- Pregnant women have a slippery and slightly rapid pulse.

- Tall people have a longer pulse area than normal. Short people have a shorter pulse area.

- Thin people with little flesh under the skin of their wrist often have a pulse that feels as though it is floating or large. Heavier people’s pulses tend to feel sunken.

- When healthy people have no signs of illness, but their six pulses are sunken, this is called

six yīn pulses.

- When healthy people with no signs of illness, but their six pulses are surging, this is called

six yáng pulses.

- People engaged in mental work tend to have weaker pulses than those engaged in physical labor.

- Athletes have a moderate (slightly slow) pulse.

- After physical exertion, the pulse is often racing.

- In sleep, the pulse is slow or moderate.

- After eating or after drinking alcohol, the pulse is more rapid and forceful than usual.

- Affect-mind stimulus causes temporary changes in the pulse. Joy causes the pulse to become moderate. Anger makes the pulse more urgent. Fright can give rise to a stirred pulse.

- The pulse may vary according to season. This is discussed under the morbid pulses below.

These variations are all within the bounds of normal health. Some people display congenital irregularities such as a particularly narrow artery, which makes the pulse comparatively fine. Some people have a pulse on the back of the wrist,

where the artery runs around the posterior surface of the styloid process of the radius. These anomalies have no significance in diagnosis.

Morbid Pulses

Depth

Floating pulse (浮脉 fú mài)

- Felt under a light touch but vacuous at the deep level. It can be felt as soon as the fingers touch the skin but becomes markedly less perceptible when more pressure is applied. It is classically described as being

like wood floating on water.

- Associated with exterior patterns but may reflect insufficiency of qì in enduring in illness or after major blood loss.

In exterior patterns, the floating pulse may be indistinct in patients of heavy build, in patients with weak constitutions, or in people suffering from severe water swelling.

A floating pulse may also occur in enduring illness or after major blood loss, indicating severe insufficiency of right qì rather than an exterior pattern. It is said, A floating pulse in enduring illness is a cause for great concern.

In these cases, it differs from the floating pulse of externally contracted febrile disease in that it is slightly less pronounced at the superficial level and markedly less pronounced at the deep level. Hence, it is sometimes described as a vacuous floating pulse.

In summer, the pulse of healthy individuals may be slightly floating.

Related pulses:

Scattered pulse (散脉 sǎn mài): Also called dispersed pulse, this is a large floating pulse without root. It is large at the superficial level. Lacking in force, it ceases to be felt when the slightest pressure is applied; hence it is described as being without root.

It indicates dispersion of qì and blood and the impending expiration of the essential qì of the bowels and viscera. It is usually attended by critical signs.

Scallion-stalk pulse (芤脉 kōu mài): This is a large vacuous floating pulse that is empty in the middle of the vessel and felt only on the sides of the vessel. This resembles a plastic hose or drinking straw, which when pressed, will bulge at the edges but not in the middle. It is usually associated with major loss of blood or damage to yīn.

Related pulse:

Drumskin pulse (革脉 gé mài): This is a floating stringlike pulse that is empty in the middle. It indicates severe depletion of essence and blood with outward floating yáng. When essence and blood are depleted, yáng qì is deprived of its anchor and floating upward and outward. This is reflected in a pulse that is floating, stringlike and large, that is strong on the outside but empty in the middle. It is seen in blood collapse (severe loss of blood as by vomiting of blood, nosebleed, bloody stool, or bloody urine); seminal loss; miscarriage; flooding and spotting. Although it is similar to the scallion-stalk pulse in qualities and significance and is commonly referred to as such, the two should nevertheless be distinguished. The floating yáng gives this pulse a deceptive feeling of strength that the scallion-stalk pulse does not have.

Note that the character 革 gé means tanned leather but is traditionally understood here to means 鼓革 gǔ gé, a drumskin. The character 革 gé also has the meaning of change or revolution and appears in the phrase the working of change

(从革 cóng gé), the classical description of the quality of metal.

Sunken pulse (沉脉 chén mài)

- Distinct only at the deep level.

- Associated with interior patterns.

Although the sunken pulse is primarily associated with interior patterns, a tight sunken pulse may appear temporarily in exterior patterns resulting from externally contracted disease when the body’s yáng qì is obstructed.

Related pulses:

Hidden pulse (伏脉 fú mài) is even deeper than the sunken pulse and only felt when considerable pressure is applied. The Bīn Hú Mài Xué (

) by Lǐ Shí-Zhēn (Bīn-Hú) states, The hidden pulse is found by pressing through the sinews right to the bone.

It is associated with fulminant desertion of yáng qì or deep-lying internal cold. It usually appears in conjunction with severe vomiting, diarrhea, and pain.

firm pulse.

The confined pulse is sunken and forceful. It feels as though it is tied to the bone,

hence its name. It is associated with cold pain. In clinical practice, this term is now seldom used, and the pulse is described as sunken and stringlike

or sunken and replete.

It indicates yīn cold accumulating in the inner body, mounting qì (inguinal hernia), or concretions, conglomerations, accumulations, and gatherings (abdominal masses). It arises when yīn cold accumulates in the inner body, and yáng qì sinks and becomes submerged in the lower body. A confined pulse appearing in blood loss or yīn vacuity is a critical sign.

The weak pulse (弱脉 ruò mài) mentioned below is similar to the sunken pulse but, in addition to being sunken, is also fine and forceless. It indicates qì vacuity, blood vacuity, and yáng vacuity.

Speed

Rapid pulse (数脉 shuò mài)

- Six beats per respiration (or 90 or more beats per minute).

- Indicates heat. A forceful rapid pulse means repletion heat; a forceless rapid pulse means vacuity heat.

A pulse that has between five and six beats is termed a slightly rapid pulse.

The rapid pulse is usually smooth flowing, so it is often confused with the slippery pulse. However, rapid

refers exclusively to the speed, while slippery

denotes a smooth quality. The Bīn Hú Mài Xué (Bīn-Hú Sphygmology

) clearly points out: ‘Rapid and slippery’ should not be considered identical.

Rapid

refers to the speed only.

- A forceful rapid pulse indicates repletion heat and is most commonly seen in externally contracted febrile disease.

- A forceless fine rapid pulse is indicative of vacuity heat. It may be seen in

pulmonary consumption

(TB in biomedicine) manifesting as effulgent yīn vacuity fire. - A forceless large rapid pulse that suddenly feels empty when pressure is applied indicates yáng qì floating outward.

- Healthy infants have rapid pulses.

- Pregnant women have slightly rapid pulses.

Related pulse:

Racing pulse (疾脉 jí mài): A racing pulse is one having seven or more beats per respiration. It has the same significance as the rapid pulse, but greater consideration should be given to the possibility of vacuity.

Slow pulse (迟脉 chí mài)

- Four beats or less per respiration (less than 60 beats per minute).

- Mostly indicates cold. If forceful, it means

cold accumulation

(cold in the interior); if forceless, it means vacuity cold. Also seen in yáng míng (yáng míng) intestinal heat patterns.

A slow pulse means that yáng qì is failing to move the blood adequately. Repletion cold obstructs yáng qì and slows the blood flow. When yáng qì is insufficient, it cannot propel the blood. However, a slow pulse is not associated exclusively with cold. A slow pulse may occur in any illness involving insufficiency of yáng qì or obstruction of the qì dynamic as by phlegm turbidity or static blood. It may also occur in yáng míng (yáng míng) intestinal heat patterns or dryness-heat constipation, where the blockage in the large intestine inhibits the flow of qì.

In pregnancy, a slow pulse indicates uterine vacuity cold

and insecurity of fetal qì,

which threatens miscarriage.

Related pulse:

Moderate pulse (缓脉 huǎn mài): The moderate pulse lies between the normal pulse and the slow pulse. It has more than three beats per respiration. It is not an indication of morbidity.

It is important to note that the term moderate pulse

is used in different senses. In addition to denoting a slightly slow pulse, it can also mean not urgent or gentle and smooth.

Force

Replete pulse (实脉 shí mài)

- Forceful at all three positions (inch, bar, and cubit) light or heavy pressure.

- Indicates repletion of any kind; abundance of qì and blood; healthy individuals.

The replete pulse means that qì and blood are abundant and fill the vessels completely, making the pulse forceful. It is sometimes seen in healthy individuals, reflecting the health of qì and blood. In illness, it means that although evil qì is exuberant, right qì is healthy and putting up a strong fight (evil and right contending with each other

).

The replete pulse is like the surging pulse but is equally forceful when it arrives as when it departs. It indicates that although the body is afflicted by and exuberant evil, right qì is still holding firm.

In enduring illness, the appearance of a replete pulse can portend the outward desertion yáng qì.

Vacuous pulse (虛脈 xū mài)

- Forceless at all three positions (inch, bar, and cubit) and when light or heavy pressure is applied.

- Indicates vacuity of any kind.

When qì is not strong enough to move the blood effectively, the pulse is forceless. When blood is insufficient and fails to fill the vessels, the pulse feels empty and vacuous. It reflects qì vacuity, blood vacuity, and bowel and visceral vacuity.

Weak pulse (弱脉 ruò mài)

- Extremely soft, sunken, and fine.

- Indicates insufficiency of qì and blood, and yáng vacuity.

When blood is insufficient, it does not fill the vessels, so the pulse is fine. When qì is insufficient, the pulse lacks in force, so the pulse is soft. When yáng is vacuous, it lacks driving power, so the pulse is sunken.

A weak pulse after illness is a favorable sign. A weak pulse in an illness of recent onset with evil repletion is an unfavorable sign.

Fluency

Slippery pulse (滑脈 huá mài)

- Smooth and flowing. Classically described as

pearls rolling in a dish

orsmall fish swimming.

- Indicates phlegm-rheum, food stagnation, or repletion heat. Also occurs in healthy individuals and pregnancy.

Although the smooth pulse indicates phlegm-rheum, food stagnation, or repletion heat, it may also occur in healthy people, indicating an abundance of qì and blood. It is common in pregnancy, particularly in the early stages when additional blood is produced to nourish the fetus.

Related pulse:

Stirred pulse (動脈 dòng mài). The stirred pulse is a combination of the rapid, short, and slippery pulses, most distinct at the cubit position. Often described as being short as a bean.

It signifies pain or fear and fright. It is seen when blood obstructs qì, giving rise to pain. It is also seen when fright causes qì and blood to move chaotically.

Rough pulse (涩脉 sè mài)

- Does not flow smoothly (opposite of the slippery pulse). Classically described as being

like a knife scraping bamboo.

- Indicates blood stasis or dual vacuity of qì and blood.

The rough pulse tends to be fine, is generally slightly slower than the normal pulse, and has been described as fine, slow, short, rough, and beating with difficulty.

In English, the rough pulse is sometimes called a choppy pulse

or a dry pulse.

Tension

Stringlike pulse (弦脈 xián mài)

- Long and taut. Feels like the string of a musical instrument. Note that the character 弦 xián contains 弓 gōng, meaning a bow, which may have influenced the English translation of

bowstring pulse.

- Indicates liver or gallbladder disease, phlegm-rheum, pain patterns, and malarial disease.

The liver regulates the qì dynamic of the body. It likes softness and is averse to hardness. A stringlike pulse can arise from any factor that impedes the qì flow of the vessels, including disturbances of the liver’s free coursing and upbearing-effusion actions, the obstructive effects of phlegm-rheum, or channel and network vessel obstructions manifesting in pain. Hence, it is seen in depressed liver qì, liver qì invading the spleen, ascendant hyperactivity of liver yáng, phlegm-rheum patterns, and in pain attributable to any cause. It is also seen in malarial disease.

A stringlike pulse that is very fine like the blade of a knife is a sign of severe stomach qì vacuity. This is seen in vacuity taxation

patterns (severe enduring vacuity patterns).

Drumskin pulse (革脉 gé mài): This is a floating and stringlike pulse that is empty in the middle. It is discussed under floating pulse

above.

Tight pulse (紧脉 jǐn mài)

- Taut and very forceful. Like a tightly pulled and twisted rope.

- Indicates cold, pain, and abiding food (enduring food accumulation).

This is a markedly forceful stringlike pulse. Stringlike

describes the form, whereas tight

describes the form and strength. A tight pulse is always stringlike, while a stringlike pulse is not necessarily tight. A tight pulse is associated with cold and pain.

When cold invades the body, it impedes the movement of yáng qì. When right qì fights the evil, the vessels become tense, making the pulse tight. When cold evil is in the exterior, the pulse is floating and tight. When cold evil is in the interior, the pulse is sunken and tight. Acute pain and abiding food similarly give rise to a powerful struggle between evil and right.

Soggy pulse (濡脉 rú mài)

- Floating, fine, and soft; indistinct when pressure is applied.

- Indicates vacuity and dampness.

When yīn is vacuous and fails to restrain yáng, the pulse is floating and soft; when essence and blood are insufficient, the pulse is fine and weak. The soggy pulse often indicates dual vacuity of qì and blood or damp encumbrance.

Related pulses:

Faint pulse (微脉 wēi mài): This pulse is extremely fine and forceless, indistinct or almost imperceptible. It indicates qì and blood vacuity desertion. When very imperceptible, it is described as a

(脉微欲绝 mài wēi yù jué).

The vacuous pulse (虛脈 xū mài) mentioned above is weak like the soggy pulse but differs in that it is large rather than fine.

Breadth

Surging pulse (洪脉 hóng mài)

- Broad (large), full, forceful at all levels, especially the superficial.

- Indicates exuberant heat (as in exuberant heat in the qì aspect). It can also indicate exuberant evil with debilitated right qì.

Broad, large, and forceful, the surging pulse has a beat that is longer and more forceful on arrival than on departure; hence, it is described as coming forcefully and going away feebly.

It is thought of as waves lashing against the rocks, with an initial strong swell followed by a sharp but calm ebbing away.

Exuberant heat in the inner body causes the vessels to dilate so that they swell with qì and blood. Hence, the surging pulse indicates exuberant heat, as seen for example in yáng brightness (yáng míng) and qì-aspect exuberant heat patterns of externally contracted disease.

A surging pulse can also appear in enduring disease, in vacuity taxation, or as a result of bleeding or diarrhea. Here, it is exuberant at the superficial level, but rootless at the deep level.

In hot summer weather, the pulse of a healthy individual may also be slightly surging.

Related pulses:

The replete pulse (实脉 shí mài) described above is like the surging pulse but is as forceful when it falls as when it rises. It indicates that although the body is afflicted by an exuberant evil, right qì is still holding firm.

Large pulse (大脉 dà mài). Large

simply refers to the breadth of the vessel and bears no connotation of force. However, its clinical significance is roughly the same as that of the surging pulse.

Fine pulse (细脉 xì mài)

- Feels like a well-defined fine thread. Because of this, it is sometimes called a

thready pulse

in English, although this opens to confusion with thestringlike pulse.

- Indicates blood vacuity or yīn vacuity; dual vacuity of qì and blood; dual vacuity of yīn and yáng. Also observed in dampness.

In the fine pulse, the blood vessel feels like a distinct fine thread under the fingertips. It arises when qì and blood are insufficient to fill the vessels or when dampness impedes the movement of qì and blood.

A fine pulse appearing with clouded spirit and deranged speech in warm heat disease means that the heat evil is penetrating the provisioning and blood aspects or is falling into the pericardium.

Regularity

Skipping pulse (促脉 cù mài)

- Rapid and interrupted at irregular intervals.

- Indicates repletion heat; stagnation of qì and blood; phlegm-rheum; or abiding food. It may also indicate debilitation of visceral qì and yīn-blood vacuity.

When yáng is exuberant and yīn cannot counterbalance it, the pulse is rapid but does not flow regularly. Hence, the pulse halts now and then. When original qì is severely debilitated, visceral qì is weak, and yīn-blood is scant, the qì of the vessels becomes irregular. In such cases, the pulse is not only rapid and interrupted but also fine.

Bound pulse (结脉 jié mài)

- Moderate (slightly slow) and interrupted at irregular intervals.

- Indicates exuberant yīn and binding qì, cold phlegm, blood stasis, and concretions, conglomerations, accumulations, and gatherings.

When yīn is exuberant and yīn evils (cold, phlegm, static blood) bind and clog, yáng qì cannot move smoothly, so the pulse is slow, but forceful. In enduring illness and vacuity-detriment where yáng qì is faint and weak, the pulse may be bound and forceless.

Intermittent pulse (代脉 dài mài)

- Interrupted at regular intervals; the interruptions are long.

- Indicates debilitation of visceral qì. May also indicate pain patterns (e.g., impediment), wind patterns, excesses of the seven affects (such as fright or fear), and injuries from knocks and falls. It is sometimes seen in pregnancy.

When visceral qì is weak, qì and blood are depleted, the qì of the vessels does not ensure vigorous steady flow, so the pulse is intermittent and vacuous. In the other conditions mentioned, evils obstruct qì and cause it to bind and move falteringly so that the pulse is intermittent and forceful.

Length

Long pulse (长脉 cháng mài)

- Felt beyond the inch and cubit, long and straight.

- Yáng patterns; repletion patterns; heat patterns. Also occurs in healthy people.

A forceful long pulse can be caused by exuberant internal heat and hyperactivity of yáng. A long pulse that is harmonious and moderate in its qualities may be observed in healthy individuals. This pulse is seldom mentioned in disease and pattern descriptions.

Short pulse (短脉 duǎn mài)

- A pulse that does not fill the three positions and is only felt at the bar.

- Indicates qì stagnation when forceful and qì vacuity when forceless.

A short pulse indicates qì stagnation and conditions associated with it, such as stagnant phlegm and food accumulations. This pulse is seldom mentioned in disease and pattern descriptions.

| Categorization of Pulses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse | Description | Significance | |

| Floating Type: Felt when light pressure is applied | |||

| Floating | Felt under light pressure, less distinct under heavy pressure | Exterior patterns; severe vacuity patterns | |

| Scattered | Floating and large, without root | Dispersion of original qì and exhaustion of the bowels and viscera | |

| Scallion-Stalk | Floating and large, hollow in the middle like a scallion stalk | Blood loss; damage to yīn | |

| Drumskin | Floating and stringlike; hollow in the middle, like the skin of a drum | Blood collapse; seminal loss; miscarriage; flooding and spotting | |

| Sunken Type: Felt only when heavy pressure is applied | |||

| Sunken | Felt only under heavy pressure | Interior patterns | |

| Hidden | Felt only when the fingers press again sinew and bone | Fulminant desertion of yáng qì or deep-lying internal cold; occurs in extreme pain, vomiting, or diarrhea | |

| Confined | Firm and hard. It has 5 qualities: sunken, stringlike, large, replete, and long | Exuberant internal yīn cold causing mounting qì or to concretions and accumulations | |

| Weak | See under vacuous-type pulsesbelow. | ||

| Rapid Type: More than 5 beats per respiration | |||

| Rapid | 6 beats per respiration | Heat patterns (vacuity or repletion); yáng qì floating outward | |

| Racing | 7+ beats per respiration | As for rapid pulse, but yáng qì floating outward is more likely | |

| Stirred | Short as a bean, slippery, rapid, and forceful | Pain; fright and fear | |

| Skipping | Rapid and interrupted at irregular intervals | Repletion heat; stagnation of qì and blood; phlegm-rheum; or food accumulation; debilitation of visceral qì | |

| Slow Type: Four or less beats per respiration | |||

| Slow | Less than 4 beats per respiration | Cold patterns | |

| Moderate | 4 beats per respiration | Dampness disease; spleen-stomach qì vacuity | |

| Rough | Does not flow smoothly | Blood stasis or dual vacuity of blood and qì | |

| Bound | Slow and interrupted at irregular intervals | Yīn evils (cold, phlegm, static blood) obstructing qì | |

| Intermittent | Soft and weak with long pauses at relatively regular intervals | Debilitation of visceral qì; pain; fright or fear; injury from knocks and falls | |

| Vacuous Type: Forceless | |||

| Vacuous | Forceless at all positions and all levels; empty and soft under pressure | Vacuity patterns, especially dual vacuity of qì and blood | |

| Soggy | Fine, floating, soft, and lacking in force | Vacuity; dampness | |

| Fine | Feels like a well-defined thread under the fingers | Blood vacuity; yīn-vacuity; dual vacuity of qì and blood; dual vacuity of yīn and yáng; dampness | |

| Weak | Soft, sunken, and fine | Dual vacuity of qì and blood; yáng qì vacuity | |

| Faint | Extremely fine and forceless, almost imperceptible | Qì and blood vacuity desertion | |

| Rough | See under Slow Typeabove. | ||

| Short | Only felt at the bar position | Qì stagnation, blood stasis, phlegm, or food accumulation if forceful; qì vacuity if forceless | |

| Replete Type: Forceful | |||

| Replete | Firm and forceful at all positions and levels | Repletion patterns; healthy individuals | |

| Slippery | A smooth-flowing pulse; like pearls rolling in a dish | Phlegm-rheum; food accumulation; repletion heat; healthy people; pregnancy | |

| Surging | Broad (large), full, and forceful, at all levels, especially the superficial | Repletion heat | |

| Stringlike | Feels like the string of a musical instrument | Diseases of the liver and gallbladder (esp. ascendant hyperactivity of liver yáng); pain; phlegm-rheum patterns | |

| Tight | A stringlike pulse with marked forcefulness | Cold; pain | |

| Long | A pulse that can be felt beyond the inch, bar, and cubit. | Yáng patterns, heat patterns, and repletion patterns; healthy individuals | |

Pulse Combinations

More than one pulse quality may appear at the same time. This is called a combination pulse.

When two pulse conditions appear at the same time, such as floating and rapid, this is called a double combination pulse.

The simultaneous appearance of three pulse conditions, such as short, slippery, and rapid, is called a triple combination pulse.

There are also combinations of four and five pulse conditions. Of course, conflicting pulses (rapid and slow, surging and fine, slippery and rough) cannot appear together.

The clinical significance of a combined pulse is the sum of the significance of the individual pulses that compose it. For example, a floating pulse suggests an exterior condition, while a rapid pulse means heat. When the two pulses appear together as a double combination, they indicate exterior heat. Similarly, a sunken pulse points to the interior, and a slow pulse means cold; hence a pulse that is sunken and slow means interior cold.

The most common combinations are as follows:

Floating and tight: Exterior cold patterns resulting from external contraction of cold evil; or wind-cold impediment (bì) disease.

Floating and moderate: Greater yáng (tài yáng) wind strike with damage to defense by wind evil and provisioning-defense disharmony.

Floating and rapid: Exterior heat patterns attributable to wind-heat assailing the exterior.

Floating and slippery: Exterior patterns complicated by phlegm. Often seen contraction of external evils in patients with pre-existing phlegm-damp.

Sunken and tight: Interior cold.

Sunken and slow: Interior cold.

Sunken and moderate: Spleen vacuity with water-damp collecting in the interior.

Sunken and rough: Blood stasis, especially in patients with yáng vacuity with congealing cold causing blood stasis.

Sunken and fine: Yīn vacuity or blood vacuity.

Sunken and stringlike: Depressed liver qì or water-rheum collecting in the interior.

Sunken, fine, and rapid: Yīn vacuity with internal heat; blood vacuity.

Stringlike and tight: Cold patterns; pain. Often seen in cold stagnating in the liver vessel or when liver qì depression gives rise to pain.

Stringlike, slippery, and rapid: Liver fire complicated by phlegm; liver-gallbladder damp-heat; or liver yáng harassing the upper body with phlegm-fire brewing internally.

Stringlike and fine: Liver-kidney yīn vacuity; blood vacuity with depressed liver qì; liver depression and spleen vacuity.

Slippery and rapid: Phlegm-heat, phlegm-fire, damp-heat, or food accumulation with internal heat.

Surging and rapid: Yáng míng (yáng míng) channel patterns; exuberant qì-aspect heat.

The Seven Strange Pulses

The seven strange pulses

(七怪脉 qī guài mài) are pulses that have no stomach, spirit, or root. They indicate critical conditions. They are also called

(真脏脉 zhēn zàng mài),

(败脉 bài mài),

(死脉 sǐ mài), and

(绝脉 jué mài).

From the biomedical standpoint, these pulses mostly indicate arrhythmia due to organic rather than functional heart disease.

Seething cauldron pulse (釜沸脉 fǔ fèi mài): A pulse that is just below the skin and that is rapid and floating so that it is difficult to count the beats, like water seething in a cauldron. It indicates extreme heat with extreme depletion of yīn humor. Mostly seen before death.

Darting shrimp pulse (虾游脉 xiā yóu mài): A pulse that is just below the skin like a darting shrimp. It arrives almost imperceptibly and vanishes with a flick. It occurs when yáng qì has lost the support of yīn qì (solitary yáng

) and becomes agitated. It indicates expiration of large intestine qì.

Leaking roof pulse (屋漏脉 wū lòu mài): A pulse that is felt in the sinews and flesh. It arrives forcelessly at long and irregular intervals, like water dripping from a leaking roof. It indicates expiration of stomach qì, provisioning, and defense.

Pecking sparrow pulse (雀啄脉 què zhuó mài): An urgent rapid pulse of irregular rhythm that stops and starts, like a sparrow pecking for food. It indicates severe spleen vacuity.

Untwining rope pulse (解索脉 jiě suǒ mài): A pulse that is now loose, now tight, sometimes rapid and sometimes slow, like an untwining rope. It indicates the collapse of kidney and life-gate qì.

Flicking stone pulse (弹石脉 tán shí mài): A sunken replete pulse that is hard without any softness or gentleness, like a stone flicked by a finger. It indicates expiration of kidney qì.

Women’s Pulses

Attention is paid to changes in the pulse due to menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth.

Menstruation Pulses

When pulse of the left bar and cubit is larger and more surging than that of the right hand and there is bitter taste in the mouth, lack of bodily warmth, and absence of abdominal distension, the menstrual period is about to arrive. When the inch and bar pulse is normal, but the cubit cannot be felt, this is a sign that menstruation will not be smooth.

Amenorrhea takes the form of vacuity or repletion. When the cubit is vacuous, fine, and rough, this is vacuity amenorrhea due to lack of blood. If the cubit pulse is stringlike and rough, it is repletion amenorrhea.

Pregnancy Pulses

A sexually active woman may be pregnant if her periods cease, if her pulse becomes slippery, rapid, and flowing harmoniously,

if she desires unusual foods such as sour things, and/or if she experiences vomiting. Note that the time of taking the pulse is important, since a pulse that is both slippery and racing after an afternoon nap is not necessarily is a sign of pregnancy, but rather to variations in the balance of yīn, yáng, qì, and blood throughout the day.

The Sù Wèn (Chapter 40) describes pregnancy as a state in which the body is affected by illness but there is no evil pulse.

In other words, a woman showing signs that might be mistaken for illness, especially absence of menstruation and changes in food preferences, may be pregnant if the pulse is pulse normal in size at the three positions and at the superficial and deep levels, without any stringlike, scallion-stalk or rough qualities.

The Sù Wèn (Chapter 18) states: When the hand lesser yīn (shào yīn) channel pulse shows pronounced stirring, this means pregnancy.

This is taken to mean that when menstruation ceases, and the left inch pulse is slippery and stirring (active), this is a sign of blood gathering to nurture the fetus.

The Sù Wèn (Chapter 18) states: When the yīn [pulse] beats differently from the yáng [pulse], this means [that she is] with child.

The yīn [pulse]

is the cubit, reflecting the kidney, which is connected to the uterus so that when the fetal qì stirs in pregnancy, the cubit pulse of both hands become slippery and rapid, beating against the fingers. The yáng [pulse]

is the inch pulse. However, in pregnancy, the same forceful beat is not felt here.

However, the pregnancy pulse is slippery and rapid, and hence different from pathological pulses. In amenorrhea, where periods cease for reasons other than pregnancy, the pulse is vacuous, fine and rough in vacuity conditions or stringlike or rough in repletion conditions. If there are abdominal masses (accumulations and gatherings), the pulse is usually stringlike, tight, sunken, and bound or sunken and confined rather than slippery. Taxation damage may present with a rapid pulse, but such a pulse is usually also rough, while a pregnancy pulse is rapid and slippery.

Live and Dead Fetus Pulses

A pulse that is surging and forceful at the deep level is a sign that the fetus is alive, while a rough pulse, which reflects the expiration of yáng qì, means that the fetus is dead and can only be palpably felt as an abdominal mass.

Wáng Shū-Hé (王叔和) explains this in the Mài Jīng (脉经 The Pulse Classic

): When the inch opening (wrist pulse) is surging and rough, the surging quality reflects qì, while the rough quality reflects the state of the blood. Qì stirring at the cinnabar field (dān tián) means that the body is warm, while roughness, reflecting a condition in the lower body, means that the fetus is as cold as ice. With yáng qì [prominent], the fetus lives, while with yīn qì [prominent] the fetus has ceased [to live]. In identifying yīn and yáng, attention should be paid to the firmness of the lower body (abdomen). If yáng has expired, it will feel like a cup.

This means that in pregnancy, yáng qì should stir in the cinnabar field (dān tián), which is reflected in a pulse that is surging at the deep level. This indicates the fetus is receiving due warmth and nourishment. Conversely, a pulse that is rough at the deep level means that essence and blood are insufficient to nourish the fetus.

Pre-Delivery Pulses

The pulse can reveal when a woman is about to give birth. The seventh-century Zhū Bìng Yuán Hòu Lùn (The

) states: When a pregnant woman’s cubit pulse turns rapidly like a severed string or spinning pearls, this means delivery is imminent.

Chinese medicine observes that conspicuous throbbing of the tip sections of the middle fingers is also a sign of imminent delivery.

Infants’ and Children’s Pulses

The

Single-Finger Pulse-Taking

The child’s hand is held in the practitioner’s left hand. For children under three, the right thumb is placed on the radial prominence. For children of over four years, the thumb is placed on the midline of the radial prominence, which marks the bar positionand is rolled slightly to feel all positions. For children of seven or eight years old, the thumb is shifted to feel the three positions. For children of over nine or ten years old, the thumb is variously placed on the inch, bar, and cubit to feel the pulse. For, children over 15 years of age, the pulse is examined in the same three-position method applied to adults.

Interpretation

In infants of under three, seven or eight beats per complete respiration is the norm. In children of five or six, six beats per respiration is the normal pulse, while seven or more beats constitutes a rapid pulse and fewer than four or five beats counts as a slow pulse. Rather than trying to identify the pulse in terms of the twenty-eight standard pulses seen in adults, the practitioner simply determines whether the pulse is floating or sunken, slow or rapid, weak or strong, hurried or unhurried in order to identify yīn or yáng conditions, cold or heat conditions, and interior or exterior conditions, and the relative status of evil qì and right qì.

- Floating and rapid is yáng, while sunken and slow is yīn.

- Strong and weak determine whether the condition is one of vacuity or repletion.

- Urgent (hurried) or moderate (here meaning not urgent) determine the state of right and evil.

- Rapid means heat, while slow means cold.

- Sunken and slippery means phlegm or food stagnation, while floating and slippery means wind-phlegm.

- Tight and urgent means cold, while harmonious and moderate (unhurried) means dampness.

- Irregular breadth means accumulation and stagnation.

- In adults, kidney qì is reflected in the pulse at the deep level. In infants and children, kidney qì has not yet reached fullness. Hence, whatever pulse quality is detected in children, no pulse is usually felt at the deep level. If a pulse is felt, then this corresponds to the firm (confined) pulse of adults.

Significance of the Pulse

Locus and Nature of Illness

However complex its manifestations are, illness can always be analyzed in terms of exterior and interior, cold and heat, vacuity and repletion, and locus among the bowels and viscera. All these aspects are detectable in the pulse.

Exterior-interior: A floating pulse indicates illness in the exterior, while a sunken pulse indicates illness in the interior.

Cold and heat: Sunken pulses and tight pulses indicate cold. Rapid and slippery pulses usually indicate heat.

Vacuity and repletion: Vacuous, weak, fine, and faint pulses indicate vacuity, while replete, surging, stringlike, and long pulses usually indicate repletion.

Bowels and viscera: The locus of illness among the bowels and viscera can often be determined from differences in the pulse between the left and right hand and between the three positions (inch, bar, and cubit) of each hand. To recap:

- Right inch: lung. Left inch, heart.

- Right bar: stomach and spleen. Left bar: liver and gallbladder.

- Right and left cubit: kidney.

Determining Cause and Pattern

The causes of disease may be reflected in the pulse. For example, prolonged worry and anxiety or frustration is often reflected in the stringlike or rough pulse. Food stagnating in the stomach and intestines due to voracious eating and drinking is usually reflected in a slippery rapid pulse.

Some disease patterns are reflected in specific pulses. A good example is found in Chapter 9 of the Shāng Hán Lùn (On Cold Damage

), where it says, When the yáng [pulses] are faint and the yīn [pulses] are stringlike, this means chest impediment and pain.

Here, yáng pulses are faint

refers to the inch position being faint and weak, indicating insufficiency of chest yáng, while yīn pulses are stringlike

refers to the stringlike and urgent feel of the cubit pulse, which reflects exuberant internal yīn evil. The combination of the two reflects the yáng vacuity in the upper burner and the yīn evil in the lower burner exploiting the vacuity to surge upward, which gives rise to the chest impediment.

Another example is found in Chapter 14 of the Shāng Hán Lùn (On Cold Damage

), where it says, When the inch opening pulse is sunken and slow,

sunken

means water, while slow

means cold… When the lesser yang pulse is low and the lesser yīn (shào yīn) pulse is fine, [we see] inhibited urination in men and stopped menstrual flow in women.

Advance, Regression, and Prognosis

The pulse provides some indication of the advance or regression of illness and prognosis. Some examples follow:

- In enduring illness, a pulse that becomes more harmonious and forceful means that stomach qì is gradually being restored and the illness is regressing.

- In vacuity taxation, blood loss, or enduring diarrhea, the appearance of a scallion-stalk or drumskin pulse indicates a severe condition in which right qì is becoming weaker.

- In externally contracted disease where heat effusion is abating, the appearance of a harmonious pulse means that recovery can be expected, whereas the appearance of an urgent rapid pulse with vexation and agitation means that the condition is worsening.

- In externally contracted disease marked by shiver sweating, if the pulse becomes more tranquil after sweating, this is a sign that the illness is abating. If the pulse instead becomes agitated and racing, while the heat effusion fails to abate, this means that the illness is getting worse.

Congruence and Incongruence of Pulse and Signs

The pulse examination is only one method of gathering diagnostic information. The pulse reflects different conditions to different degrees and with varying accuracy. Its value is therefore relative rather than absolute. A rapid pulse, for instance, usually signifies heat but may also occur in vacuity patterns. It is always essential to evaluate the pulse against the presenting signs in accordance with the principle of correlating all four examinations.

When a condition is characterized by the pulse that would normally be expected given the presenting symptoms, we say that the pulse is congruent with the signs. When the pulse is not of the quality expected, we say that the pulse and signs are incongruent. Congruence is usually a favorable sign, while incongruence is unfavorable. Sometimes the pulse is a false reflection of the true nature of the condition, in which case the correlation of all four examinations reveals the precedence of pulse or signs.

Favorable and Unfavorable Prognosis

Congruence between the pulse and signs is usually favorable, while incongruence is unfavorable.

- In disease of sudden onset marked by repletion signs, a floating, surging, rapid, or replete pulse is favorable, because it shows the strength of right qì and means a favorable prognosis. By contrast, a pulse that is sunken, fine, faint, or weak means that right qì cannot fight the evil and that the prognosis is less favorable.

- In enduring illness forming a vacuity pattern, a sunken, faint, fine, or weak pulse is favorable since it indicates that any evil that might have been present has weakened, providing right qì with the opportunity to regain strength. By contrast, the appearance of a pulse that is floating, surging, rapid, and replete means that the right qì is severely debilitated and that the evil is not abating.

Precedence of Pulse and Signs

When pulse and signs are incongruent, it is important to establish the relative importance of each. Two possibilities exist:

- Both factors may be the true reflections of different elements of a complex condition, as may be seen in vacuity-repletion complexes.

- Alternatively, either the pulse represents the true nature of the condition, while the signs are false; or the signs are true, while the pulse is false.

Precedence when pulse and signs are both true: An example of a vacuity repletion complex is drum distension (ascites) accompanied by a forceless weak faint pulse. Here, the signs reflect the evil repletion, while the pulse reflects the vacuity of right qì. Thus, both truly reflect different aspects of the condition. In such cases, it is important to correlate all four examinations to determine whether the repletion or the vacuity is predominant, since the success of treatment may depend on it. If the evil repletion is found to be more pronounced than the vacuity of right, the signs override the pulse, and the principle of attack followed by supplementation is applied. If the right qì vacuity is more pronounced than the evil repletion, the pulse overrides the signs, and the principle of supplementation followed by attack applies. Most often, the principle of simultaneous supplementation and attack is applied.

True signs taking precedence over a false pulse: An example of this is a condition of abdominal pain that refuses pressure, constipation, a thick burnt yellow tongue fur, and a slow fine pulse. The signs faithfully reflect gastrointestinal heat bind, while the pulse reflects impairment of the qì dynamic inhibiting the smooth flow of qì and blood through the vessels, giving an erroneous impression of vacuity cold. Here, the signs should be given precedence over the pulse, and the condition should be treated by emergency precipitation of the repletion. Giving precedence to the signs accordance with the principle applied in pattern identification of distinguishing true and false.

True pulse taking precedence over false signs: An example of this is an internal heat block, marked by a sunken rapid pulse together with reversal cold of the limbs. Here, the pulse faithfully reflects the true condition. The signs only reflect the misleading presence of cold attributable to the confinement of heat in the interior. Thus, here, the pulse overrides the signs. When this is judged accurately, treatment can be provided to outthrust the interior heat.

Hints for determining precedence: Usually, where a vacuity-repletion complex accounts for incongruity between pulse and sign, it is readily identifiable. Greater difficulty lies in evaluating the relative severity of vacuity and repletion and in deciding whether the pulse or signs should govern the choice of treatment. Where incongruity involves a false factor, the true factor is usually readily identifiable, whereas the false factor tends to cause confusion. The solution in both cases lies in thorough examination and careful analysis.

In the example of gastrointestinal heat bind, careful observation reveals the pulse to be slow, fine, and forceful, as distinct from the forceless fine slow pulse that would otherwise indicate a vacuity pattern.

In the example of the internal heat block with reversal cold of the limbs, all the other signs point to the presence of heat. If the cause of reversal cold of the limbs were yáng collapse vacuity desertion, there would be no signs of heat. Thus, the heat signs must be properly identified to avoid the mistake of evacuating vacuity and replenishing repletion,

that is, making vacuity or repletion worse. As the Bīn Hú Mài Xué (Bīn-Hú Sphygmology

) states: The pulse ranks least among the four examinations. If the whole [picture] is to be brought together, all four examinations must be carried out.

For further discussion of true and false signs, see eight-principle pattern identification.

Back to search result Previous Next