Search in dictionary

History 1: The Formative Period

历史沿革1:形成期 〔歷史沿革1:形成期〕 lì shǐ yán gé 1: xíng chéng qī

The formative period is discussed from three viewpoints: a move from supernatural to natural explanations of illness, the application of philosophical concepts, and inspiration from economic, political and social change.

Contents

- From Supernatural to Natural Explanations of Illness

- Applying the Philosophical Concepts of Qì, Yīn-Yáng, and the Five Phases

- Inspiration from Economic, Political, and Social Change

From Supernatural to Natural Explanations of Illness

Ancient bronze inscriptions and later iron artifacts, oracle shells and bones, and finally historical and other records from the Shāng and Zhōu Dynasties (1600–256 BCE) provide the earliest clear evidence of Chinese thought on health and disease. During this period, people attributed illnesses largely to the influence of ancestors, spirits, and demons. Religious healers and shamans thus prevented and treated sickness by propitiations to these powers. Such beliefs in the influence of supernatural forces on human health have taken different forms over time. They continue to the present. In Taiwan, for example, shamanic medical rituals are practiced to this day.[6] For more on this topic, see external influences 1: supernatural beliefs.

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

A system of philosophical and ethical teachings founded by Confucius ( |

In the last few centuries before the Common Era (BCE), a new understanding of the body and its afflictions developed alongside and partly replaced this earlier one. This new conception rested on the idea that health and sickness were subject to natural laws, and that mastery of these laws would allow for intervention in disease processes and even prevent illness from arising.

Such understanding did not arrive spontaneously. Rather it came in the wake of the flowering of deep philosophical thought. Centuries of political turmoil and social chaos stimulated intelligent Chinese minds yearning for peace and order. They began to think about social and philosophical issues in the context of the order of the natural world.

In the social and political realm, Confucius and his followers developed and propounded the notion that peace and order were attainable by establishing rules of conduct for all members of society. These rules centered on obedience toward superiors and benevolence toward inferiors. The Confucians conceived the right way of doing things as the Dào (literally Way

).

Shortly after the establishment of Confucianism, and partly in reaction to it, Lǎo Zǐ and his followers preached a doctrine of returning to a simpler life that shunned the trammels of greed and desire and rejected the Confucian social rules because they led to insincerity and abuse of power. These thinkers also adopted the notion of the Dào, but for them it meant the way or the laws of the universe as a whole. Because of the centrality of this concept, they became known as Daoists.

We will speak more of the influence of Confucianism and Daoism on Chinese medicine in external influences 2: Confucianism and external influences 3: Daoism.

| Daoism |

|---|

Philosophical Daoism developed from the 5th to the 3rd centuries BCE; its tenets are found in the Dào Dé Jīng, traditionally attributed to Lǎo Zǐ, and in the text known as Zhuāng Zǐ after its author. According to this philosophy, the ultimate reality is the Dào [lit., Way], of which being and non-being, life and death are merely aspects. Adepts achieve union with the Dào through silence, stillness, intuitive contemplation and acting through nonaction( A religious Daoism evolved in the 3rd century C.E., which incorporated Buddhist features and developed its own monastic system and ritual practices. In contrast to the Buddhist concept of reincarnation and the goal of Nirvana, religious Daoists aimed at the physical transformation of the body to attain immortality in this world. Daoism is described in greater detail in external influences 3: Daoism. |

In the realm of natural philosophy, three important ideas arose concerning the nature of the world: qì, yīn-yáng, and the five phases. These were to have an immense influence on the development of medicine.

Early philosophers of the late Zhōu period observed the behavior of clouds, mist, and vapor, which they called qì (

Later, scholar physicians of the Hàn period expanded the concept of qì to explain both the material substrates and activities of the body. Qì in condensed forms formed the flesh, bone, organs, and fluids of the body. Qì in highly diffuse forms was the basis of all activity. It could flow through the channels and network vessels, enabling each organ to perform its functions.

| Associations of Yīn and Yáng | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yīn | Yáng | |

| Original meanings | Facing away from the sun | Facing the sun |

| Kernel Ideas | Dark, cold, stillness, moistness | Light, heat, activity, dryness |

| Positions / Directions | Down, in, north | Up, out, south |

| Time | Autumn-winter, night | Spring-summer, day |

| Life cycle | Decline, death | Birth, growth, development |

| Change in size and density | Contraction, concentration | Expansion, diffusion |

| State | Solid, liquid | Gas |

| Weight | Heavy | Light |

| Movement | Downward, inward | Upward, outward |

| Gender | Female | Male |

Other natural philosophers of the time pondered the multitude of opposing but mutually complementary phenomena: dark and light, moon and sun, cold and heat, winter and summer, night and day, stasis and motion, etc. Their contribution to natural philosophy was to consider these naturally paired phenomena as belonging to two universal categories. They borrowed the two Chinese words yīn and yáng (

| The Five Phases in Nature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

| Season | Spring | Summer | Late summer | Autumn | Winter |

| Activity | Birth | Growth | Transformation | Withdrawal | Hiding/storage |

| Time | Sunrise | Midday | Afternoon | Sunset | Midnight |

| Position | East | South | Center | West | North |

| Weather | Wind | Summerheat | Dampness | Dryness | Cold |

| Color | Green-blue | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Flavor | Sour | Bitter | Sweeet | Acrid | Salty |

| Smell | Animal smell | Burnt smell | Fragrant | Fishy | Rotten |

| Animal | Chicken | Goat | Ox | Horse | Pig |

Things and phenomena of either category shared not only similar natures but also similar relationships with the opposite category. One of several types of relationship was that of interdependence. Just as there can be no such thing as heat without the existence of cold, so there is no up without down, or male without female.

This system of correspondence appears to have originated in notions of magical connections among similar or otherwise related phenomena.[7] The following quotation illustrates the application of this theory to the microcosm of human society. It reflects the conviction that rulers were intermediaries between human society and the macrocosm. In other words, rulers were the key link between the realms of Heaven, Earth, and Humankind, because they influenced the world through the yīn-yáng system of correspondence..

The most important concern of the state, upon which hinges the preservation of natural and social order, is the marriage of the prince. If the union of the king and queen is not complete, the order of the universe is disrupted. If one partner oversteps his rights, eclipses of the sun and moon occur. …The son of the heavens controls the movement of the masculine principle [yang], his wife controls the movement of the feminine principle [yin].[8]

The magical qualities of yīn and yáng are also seen in the divination practices based on the Yì Jīng (Book of Changes

), as described in paradigms, Systematic Correspondence

. However, this early conception of yīn-yáng evolved into a deterministic doctrine. In this process, explanations based on magical influence gave way to ideas of cosmic resonance and natural causality. The subject of causality in Chinese medicine is discussed in cognitive features.

The yīn-yáng doctrine can be characterized in modern terms as a system of correspondence. Yet it was not the only one of its kind. A similar system, based on five categories, also came into being. This was the doctrine of the five phases (

Elementsor Phases? |

|---|

The five phases, or wǔ xíng in Chinese, have been referred to in English as the five elementsbecause of their superficial similarity with the four elements of ancient Greek philosophy (earth, fire, air, and water), which denote four basic types of matter that created the material variety of the world through infinitely varied combinations. Although the five phases developed from the five materials,( movement, action,reflecting the reconception of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water as active qualities representing the various kinds of activity prevalent in nature at different times of the year. |

Wood, fire, earth, metal, and water were five manifestations of phenomena seen as vitally important to humans. Wood was a resource for making implements and building houses. Fire was used for heating, cooking, warding off predators, and smelting metals. Earth made it possible to grow crops and provided fodder for livestock. Metal was used for making tools, utensils, and weapons; and water was necessary for growing crops, for washing, and for maintaining life.

Each phase was further associated with qualities and functions. The living wood (plant life) was associated with expansive growth; fire with heat and upward movement; earth with producing crops; metal with the working of change—in particular the destruction of life; and finally, water with moistening and descent to low places.

These qualities associated each phase with phases in the cycle of nature. Wood was associated with springtime and the burgeoning of new plant- and animal life; fire with the torrid heat of early summer causing rapid growth; earth with the ripening of crops in late summer

; metal with harvesting of crops and the purging of nature in autumn, and water with the stillness of winter when nature goes into cold storage.

Associations with the yearly cycle of seasons allowed the phases to be mapped onto parts of the diurnal cycle and the corresponding positions of the sun: wood with morning and east, fire with midday and south; earth with afternoon and central position; metal with evening and west; water with night and north.

The association of the five phases with the cycles of nature enabled them to be understood not just as parameters of classification but also as cyclical phases, hence the English name, five phases.

Numerous other connections were made with colors, sounds, and flavors, constituting a system that made observational sense of the confusing welter of phenomena of the human world.

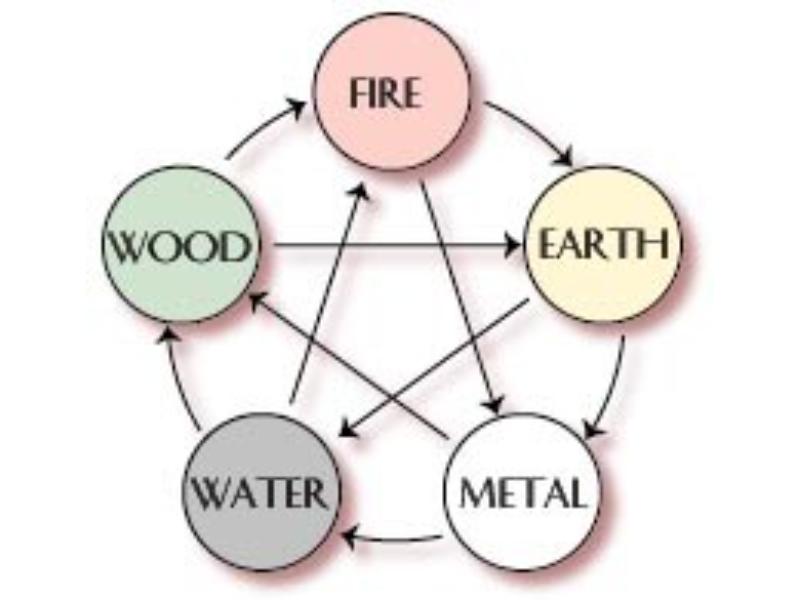

Certain relationships were seen to hold between the five phases. Among these were the engendering cycle: wood burns to produce fire; fire burns things to ashes; earth gives rise to ores that produce metal; metal causes water to condense; water produces plant life. The progress of seasons follows this order. There is also restraining cycle, whereby wood loosens earth, earth dams water, water douses fire, fire melts metal, and metal cuts wood.

Central to all the ideas of social and natural philosophers was the notion that the universe did not obey the arbitrary whims of supernatural forces or despotic rulers but was in fact subject to natural laws. By understanding those laws, human beings could take charge of their own fate and society could cure itself of its own ills.

| Basic Five-Phase Associations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Season | Weather | Position | Development |

| Wood | Spring | Wind | East | Birth |

| Fire | Summer | Summerheat | South | Growth |

| Earth | Late summer | Dampness | Center | Transformation |

| Metal | Autumn | Dryness | West | Withdrawal |

| Water | Winter | Cold | North | Storage |

These philosophical developments as a whole greatly stimulated medical thinkers in developing a concept of health and sickness based on natural phenomena and laws. The philosophical concepts of qì, yīn-yáng, and the five phases found direct applications in this new understanding of health and sickness. Even the socially oriented philosophies of Confucianism and Daoism exerted powerful background influences on the development of China’s medical traditions (see external influences).

According to the observations of these ancient medical thinkers, adequate diet, rest, and activity maintained the strength and health of the body. Ideally, individuals would receive sufficient yet not overindulgent nourishment. Any excesses of food, drink, exertion, or sexual activity were to be avoided, since they were observed to have deleterious effects on human health. Environmental influences such as cold, heat, wind, and dampness were also observed to contribute to illness, with greater susceptibility in cases of individuals in poor health. These environmental influences were seasonal in nature and capable of entering and lodging in the body, thus creating imbalances in the harmonious functioning of the organism. Imbalances led to illness. People could prevent disease by avoiding overexposure to these influences. Physicians treated disease by eliminating the offending influences and boosting any weakened bodily functions. This deterministic approach recognized the body as composed of harmoniously interacting systems functioning to maintain health.

|

| Five-phase cycles |

|---|

The Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic

) is the earliest extant major medical text, written in the Early Hàn era (first and second century BCE). Since the authors left no comprehensive explanation for their understanding of health and illness, scholars and physicians over the ages have inferred their reasoning from the text and from the historical context of the era.

The descriptions of the internal organ functions found in the Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng most likely resulted from external observations of overt biological activities (breathing, eating, urinating, and defecating), coupled with investigations undertaken by anatomical dissection. For example, the observation of a tract running from the mouth to the anus would have sparked the idea that it conducted and transformed food. Such naked-sense observation would have also led to the understanding that the bladder stores urine produced by the kidney, and that the lungs took in air, which was vital to the preservation of life. In all these cases, the functions discerned correspond roughly to those identified by modern biomedicine. Nevertheless, the functions of organs such as the liver, gallbladder, and spleen were not as directly related to outwardly manifest biological activities and hence are explained in ways that differ markedly from modern biomedicine.

Ancient Chinese physicians performed rudimentary dissection and, because warfare was prevalent, were familiar with the sight of injuries or corpses that exposed the body’s internal features. In theNàn Jīng, another of the earliest extant classical texts, we find descriptions of the shape and size of the major internal organs. However, anatomy advanced only marginally beyond this general understanding, perhaps because of the Confucian taboo against tampering with the body, which was considered disrespectful to the deceased’s parents. Unlike physicians in the West, those in China never indulged a compulsion to understand the function of organs purely in terms of their material structure and composition.

Applying the Philosophical Concepts of Qì, Yīn-Yáng, and the Five Phases

In medicine, physicians used the concepts of qì, yīn and yáng, and the five phases to classify internal organs and other body parts and explain their functions and interrelationships. These three products of natural philosophy thus provided a theoretical structure that facilitated the formulation of knowledge of basic physiological and pathological processes.

Physiology: Yīn and yáng were used to classify parts of the body, upper and outer parts being yáng and inner and lower parts being yin. They were used to classify the channels, those passing over the inner faces of the extremities being yīn and those passing over their outer faces being yáng. They were also used to classify the substances of the body: yīn qì is the material aspect of the body; it comprises the solid and liquid matter—the body and the fluids, including the blood. Yáng qì is the active aspect; it is understood as a diffuse form of qì that powers all activity within the body. Yīn and yáng were further used to classify the upward and downward, inward and outward movement of substances within the body.

| Yīn-Yáng in the Body | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yīn | Yáng | |

| Part | Exterior, back | Interior, chest, abdomen |

| Internal organs | Bowels (dispatch houses) | Viscera (storehouses) |

| Tissue | Skin, hair | Sinew, bone |

| Substances | Qì | Blood |

Yīn and yáng furnished a basis for a functional categorization of the human body by broadly distinguishing between two classes of organs, namely those that stored

substances and those that discharged

substances. The storing organs are the liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney. The discharging organs are the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, gallbladder, and bladder. We normally refer to the two classes as viscera

and bowels.

They have sometimes been described in the English literature as solid

and hollow.

In Chinese, they are called storehouse

for valuable objects, while fú derives from a word that referred to places of official business, including places where grain was collected for transportation to other parts of the country, an idea which we capture with the term dispatch house.

Because the viscera or storehouses

mostly handled the body's internal products, they were considered relatively yin. The bowels or dispatch houses,

which dealt with extrinsic substances, that is, those entering the body (notably food and drink) and waste destined for expulsion, were considered to be relatively yáng.

Yīn and yáng are not loose categories of phenomena. Each thing classed as yīn must have a yáng counterpart, and vice versa. This meant that the internal organs had to be paired. The liver (viscus) was paired with the gallbladder (bowel); the heart with the small intestine; the spleen with the stomach, the lung with the large intestine; and the kidney with the bladder. The pairings appear to reflect functional relationships or proximity in some cases, but not in all. We shall take this issue up again a little further ahead.

| Five-Phase Correspondence of the Bowels and Viscera | ||

|---|---|---|

| Phases | Viscus ( storehouse) | Bowel ( dispatch house) |

| Wood | Liver | Gallbladder |

| Fire | Heart | Small intestine |

| Earth | Spleen | Stomach |

| Metal | Lung | Large intestine |

| Water | Kidney | Bladder |

The five phases, with their numerous attributes, provided a framework for classifying internal organs. At first, correspondences differed among authors and changed over time. One early scheme was based on the correspondence of the location of the viscera to the changing position of the sun over the course of the daily cycle, from dawn in the east, to its zenith in the south, and on to dusk in the West, and to its lowest position in the north. When the body faces south, the spleen, being on the left side of the body, is closest to the east and hence was paired with wood. The lung, being the highest-positioned viscus, was closest to south and hence was paired with fire. The liver on the left is closest to the west and hence was paired with metal. The kidney, being the lowermost viscus of all, is closest to north and therefore was paired with water. An exception to the solar trajectory framework was the heart, which, located in the center of the chest, holds the central position associated with earth.

This pairing scheme of spleen with wood, lung with fire, heart with earth, liver with metal, and kidney with water was eventually replaced by a scheme adopted by the authors of the formative classics, which is still used to this day, namely the liver with wood, the heart with fire, the spleen with earth, the lung with metal, and the kidney with water. This new scheme entailed rematching the organs to the five phases on the basis, not of correspondences to the cardinal points, but to physical and functional features of the organs. The switch was no doubt prompted by increasing awareness of the organs as functional units contributing to the maintenance of health.

The five phases encompassed not only the organs but a large gamut of components of the organism, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the body.

- Five of the six bowels (

dispatch houses

): gallbladder, small intestines, stomach, large intestine, and bladder. - Five orifices: eyes, tongue, mouth, nose, and ears.

- Five body constituents: sinews, vessels, flesh, skin and body hair, and bone.

- Five blooms: nails, face, lips and

four whites,

body hair, and hair. - Five humors: tears, sweat, drool, snivel, and spittle.

- Five spiritual entities: ethereal soul, spirit, ideation, corporeal soul, and mind/memory.

- Five minds: anger, joy, thought, worry, and fear.

- Five voices: shouting, laughing, singing, weeping, and groaning.

The correspondence of components of the organism to yīn-yáng and the five phases was obviously inspired by analogies of the physical features and functions of the components deduced from observations to the qualities represented by the five phases. However, basing five-phase correspondences on observable physical and functional features posed the problem that the functions of certain organs were not fully apparent to naked-sense observation. While it would have been easy to deduce the respiratory function of the lung, the digestive function of the stomach and intestines, the urine-holding function of the bladder from external observation, subjective sensation, and simple dissection, it was clearly much harder to understand and formulate the functions of organs that show few or no visible, tangible, or subjectively felt signs of movement and that dissection reveals to contain no gross extrinsic matter such as food, stool, or urine. In the absence of observable data, yīn-yáng and five-phase associations prompted expectations that played a powerful role in suggesting possible functions.

| Analogy in Chinese Medicine |

|---|

| The physicians of Chinese antiquity tried to understand the human body and make sense of health and sickness by drawing analogies with phenomena outside the body with which they were more familiar. Certain functions were attributed to organs on the basis of yīn-yáng, five-phase, qì, and nation-paradigm analogies. See analogy vs. analysis. |

The spleen offers a clear example. The stomach as a collecting place of food, was naturally classed as a bowel (dispatch house

), and yīn-yáng theory demanded it have a corresponding viscus (storehouse

). The spleen, lying on the stomach’s underside, was naturally assumed to be functionally related to the stomach. Since it fit the definition of a solid organ that has nothing visibly passing through it, it was classed as the stomach’s corresponding viscus. Consequently, it was accorded the function of assimilating and storing the essence of grain and water

from which qì, blood, and bodily fluids are produced. Since the nutrients produced by the spleen and stomach could be seen as analogous to crops produced from the earth for human sustenance, these two organs were paired with earth among the five phases. The liver and spleen are further examples. We can assume that the free coursing function of the liver and the essence-storing function of the kidney, which have no basis in observable data, were, so to speak, grafted on to the organs by prospective analogy with their respective phases, wood and water.

Thus, the theoretical model of the physiology of the internal organs is the product of complex interaction between the systems of correspondence and data derived from naked-sense observation. Some cursory observations about this interaction are offered in Organ Features According to the Nèi Jīng under

The apparent mistakes

ancient medical scholars made in the attribution of functions, such as digestion to the spleen, may not be as significant as detractors of Chinese medicine believe. Insofar as the misascribed functions are real and disturbances of them are treatable, the fact of misattribution is of arguably little consequence. The effect of a given treatment on the spleen, the liver, kidney, or any organ is gauged not by its effects on the physical organ itself but by the degree to which it restores health.

| Imbalances of Yīn and Yáng |

|---|

|

When yáng is vacuous, there is cold. When yīn is vacuous, there is heat. When yáng prevails, there is heat. When yīn prevails, there is cold. |

Pathology: The kernel notions of yīn and yáng of cold/heat, stillness/activity were of great importance in understanding pathological conditions. Being both mutually opposed and complementary, a balance between yīn and yáng was identified as a state of good health. Any imbalances observed were associated with illness. Variations in temperature were found to be key diagnostic elements in many illnesses. Morbid states of the body marked by cold and reduced activity were observed when the body's yáng qì was weak or when it was affected by environmental cold. Conversely, states marked by heat and increased activity were observed when the body’s yīn qì was insufficient or when it was affected by environmental heat. See box on Imbalances of Yīn and Yáng

above

The five phases’ contribution to pathology is a far more complex issue. The theoretical relationships and interactions between the five phases, in the form of the four cycles, engendering (wood → fire → earth → metal → water) and restraining, overwhelming, and rebellion (wood → earth → water → fire → metal) were seen as capable of explaining relationships between components of the body. Because the phases were a classification system for seasons, colors, and internal organs, it was possible to develop sophisticated theoretical schemes explaining the occurrence of illness at different times of the year, the appearance of complexion colors in relation to disease of the viscera, and the progression of disease from one viscus to another. Five-phase approaches to diagnosis and treatment are still a feature of certain styles of acupuncture, but they are not systematically applied in medicinal therapy.

Inspiration from Economic, Political, and Social Change

The yīn-yáng and five-phase doctrines of systematic correspondence did not solely determine the Chinese medical model. The formative period of Chinese medicine was also influenced by a new determinism in social and health regulation, as well as by the economic, social, and political events occurring before and during the Qín and Hàn Dynasties.[9]

The initial unification of the Chinese empire by the first emperor of the Qín Dynasty, Qín Shǐ Huáng (

After the unification of China in 221 BCE, medical scholars created a rational model of human pathology and physiology, health, disease prevention, and therapy. This model had its roots not only in the observation of natural phenomena but also in the socio-economic, political, and cultural ideals of the time. Although individual organs and vessels had long been known to medical scholars, it was not until the late second or even the first century BCE that these individual parts were conceived as forming an organism. Each part was dependent on the others and contributed to supplying the needs of the whole body. In this context, the goal of medical intervention was the creation or restoration of order, harmony, and balance. Illness was defined primarily as disharmony and imbalance, caused by a disruption of transportation and communication resulting in weakness and vulnerability to external forces. This conception owes much to an analogy with a country composed of interdependent regions susceptible to economic and political disruption from within and outside.

The medical texts that were sealed in the Mawangdui tombs in Changsha in 167 BCE discuss eleven vessels in the body, understood to be separate and independent. Later, in the Huáng Dì Nèi Jīng (compiled in the first century BCE), the notion of eleven separate vessels gave way to the concept of twelve interconnected channels that formed a circuit traversing all major areas of the body.

The concept of interlinking vessels was gradually refined into a complex system of channels, termed storehouses and dispatch houses

that were connected by this network of channels. The twelve main channels (

The system of channels and network vessels was an elaboration of an earlier medical conception of the blood vessels. For a long time, blood vessels that were visible through the skin had been the focus of diagnosis and treatment. Determining whether the veins were full or empty and whether the skin covering them was smooth or rough furnished the physician with data concerning the state of the patient’s health. Fullness was treated by bloodletting, and emptiness by the application of heat, according to purely physical laws. Around the second century BCE, Chinese physicians came to recognize that in addition to blood, the vaporous agent they termed qì was of vital significance. Qì flowed, most importantly, in the immaterial channels permeating the deeper levels of the limbs and body. It could be manipulated, not with the pointed bloodletting stones, but with fine needles, inserted at given holes

(

A striking reflection of the influence of the new economic and political vision of the Chinese is seen in a set of very specific Nèi Jīng analogies used to describe the various organs of the body to government offices. The heart holds the Office of Sovereign; the lung holds the Office of Minister-Mentor; the spleen and stomach hold the Office of the Granaries; the liver holds the Office of General; the kidney holds the Office of Forceful Action; the small intestine holds the Office of Reception; the large intestine holds the Office of Conveyance; the gallbladder holds the Office of Justice; the bladder holds the Office of the River Island (Regional Rectifier); the triple burner holds the Office of the Ditches. These government analogies neatly summarize many aspects of the bowels and viscera.

The influence of the economic, political, and social developments of the period are of such consequence that it is apt to speak of an

Links to Other Periods

- History 2: The Early Medical Classics

- History 3: Post-Classical Evolution

- History 4: The Modern Era (1911–present)

- History 5: Internationalization