Search in dictionary

Cognitive features

认知特色 〔認知特色〕 rèn zhī tè sè

Contents

- Beliefs About Causality (natural, supernatural, magical)

- Analysis and Analogy: Complementary Approaches

- Scope and Significance of Analogy

- Intuitive Approaches (judging the inside from the outside; inward vision; and heart knowledge)

- Pragmatism, Empiricism, and Trial and Error

| Related Topics |

|---|

Many Chinese medical ideas about how the body functions and how illness arises, especially ones that differ markedly from those of modern biomedicine, cause students to wonder how they originated. For example, how did the Chinese come to regard the spleen as an organ of digestion? Why did they believe that the liver could be affected by wind? Or why did they associate anger with the liver and fear with the kidney? To gain a clearer understanding of such issues, we must take a closer look at the fabric of Chinese medicine and identify the strands that have woven together to shape it.

The first human attempts to explain health and sickness universally adduced both observed natural causes and supernatural powers. Accordingly, sickness was combatted by a mixture of symptomatic treatments and religious or magical interventions. The emergence of theoretically based medicines is marked by a growing understanding of natural causes and waning beliefs in the supernatural. The following discussion aims to show that in China the effort to understand the natural laws governing health and sickness rested not only on the analysis of observed data but also on perceived analogies between physiopathological processes within the body and phenomena observed in nature.

Human understanding of any phenomenon takes many different forms. It is primarily determined by beliefs concerning causality, i.e., why things exist, or events occur. These beliefs in turn influence what observations and discoveries are made, how reasoning proceeds, and what concepts are devised. Hence, this is the starting point for our discussion of the cognitive features of Chinese medicine.

Beliefs About Causality

Since any attempt to eliminate illness involves understanding its cause and performing interventions to treat or prevent it, both primitive healing practices and complex bodies of medical knowledge are conditioned primarily by beliefs concerning causal relationships between phenomena.

Modern scientific medicine accepts only causes that are scientifically demonstrable and consequently focuses exclusively on natural causes

to explain how disease arises and how it can be treated. However, exclusive belief in natural causes is relatively recent, and even in modern industrial societies, beliefs in non-natural causes are still widespread (e.g., faith healing, exorcism, shamanism).

In China, beliefs in natural causes, in supernatural causes, and in magical causes have given rise to distinct healing practices over the millennia. What we now know as Chinese medicine, which belongs to the literate tradition, came into existence when a new understanding of health and sickness based on natural causes began to prevail, belief in supernatural causality declined, and magical causality prompted the development of the deterministic systems of correspondence, yīn-yáng and the five phases. In this process, supernatural and magical causality were abandoned, although vestiges are still very much visible in the received corpus of Chinese medical knowledge.

Natural Causality

Belief in natural causes is universal in human society and certainly no modern development. A bruise, graze, cut, or fracture is naturally attributed to the trauma that preceded its appearance. A suddenly appearing condition, such as a cold, is ascribed to an unexpected change in the weather or to inadequate protection against the elements. Prevention involves avoidance of things likely to cause injury or illness, while treatment involves the use of anything that is empirically found to provide relief or a cure.

The literate tradition of Chinese healing that we call Chinese medicine

now only recognizes natural causes including trauma, environmental conditions (e.g., wind, cold, summerheat, dampness, dryness, and fire), intestinal worms, and dietary irregularities, psychological factors, and various imbalances arising within the body as the only causes of disease. However, this was not always the case in the healing practices of China.

Supernatural Causality

From the earliest times, illness not immediately associated with a natural cause was attributable to supernatural causes. Thus, sudden loss of consciousness leaving the patient paralyzed (stroke) or sudden seizures (epilepsy) that could not be associated with a prior event were attributed to supernatural causes, such as ancestors or gods inflicting such ailments on an individual for immoral or disrespectful behavior. Such illnesses were prevented by moral rectitude and treated by placating the supernatural forces.

In the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE), ancestors were considered to play a controlling role over the living. Accordingly, disease among the living was explained in terms of retribution by ancestors, and treatment was effected by penance and sacrifice. In the Zhōu dynasty (1050–256 BCE), characterized by political turbulence, supernatural causes of disease shifted to demons, and treatment centered upon warding them off or killing them using incantations and talismans as well as medicinals and acupuncture. See external influences 1: supernatural beliefs.

Magical Causality

Standing in contrast to natural causes are not only supernatural causes but also magical notions of causality between like or related things. Magical causality rests on the idea that one can influence something by dint of its relationship or resemblance to another thing. It is the operant principle of black magic, whereby violence applied to an effigy of a person or to something belonging to them such as a lock of their hair or one of their garments exerts a destructive effect on the actual person. Magical causality underlies many popular beliefs around the world regarding properties of plants, fruits and vegetables. In the West, for example, birthwort (Aristolochia) was believed to ease childbirth because of the resemblance of its flower to the birth canal. Eyebright was used for eye infections because of the resemblance of its flower to the human eye.

In China, magical causality manifests in numerous ways. It explains why animal phalluses and plants of phallic appearance were believed to enhance virility, why animal bones were considered to strengthen human bone, and why ginseng, the root shaped like a human being, was considered beneficial to human health. It explains why a harelip in an infant was once believed to be caused by the mother’s having caught sight of a hare or rabbit during pregnancy and why convulsions were thought to be caused by wind in the environment. Outside medicine, magical causality also underlies divination and fortune-telling practices. For example, those based on the Yì Jìng, in which patterns appearing on oracle bones or shells after burning or sets of numbers randomly generated by casting yarrow stalks are understood to reflect forces influencing human destiny.

Magical causality has not died with the rise of science. It operates in numerous Chinese astrological and other divination practices. It underlies methods of choosing auspicious dates for important events such as marriages and, now with cesarean section, even for births. Numerical or linguistic symbology is still a source of superstition among Chinese people. To this day, many Chinese avoid formally offering clocks and umbrellas as gifts because the Chinese words for these objects sound like end

(death) or separation.

Hospitals in the Chinese world sometimes label their fourth floor as 3b to avoid the number four, which sounds like the Chinese word for death.

In the West, beliefs in magical causality persist despite science-based education for generations. Many still regularly consult their horoscope. Many still hold to popular superstitions, such as the association of bad luck with the 13th floor of buildings, which derives from the magical connection between the number 13 and the ill-fated 13th apostle of Christ. For many, crossing paths with a black cat or walking under a ladder brings bad luck, while knocking on wood, tossing spilled salt over one’s shoulder, or saying bless you

after someone sneezes avoids it. A feel for magical causality lurks in a continuing fascination with strange coincidences,

something that psychologist Carl G. Jung formulated into the concept of synchronicity. Therefore, we must bear in mind that for early Chinese healers, whose tools for investigating physical causality were limited, magical causality would have appeared much more plausible than it does to us.

The Growing Predominance Of Natural Causality

In ancient times, different illnesses might be explained by different causes. Thus, for example, a common cold might be explained by natural causes such as exposure to the elements, while a sudden pain in the chest and loss of consciousness might be explained by supernatural or magical causes.

Gradually, the notion arose that things previously explained by supernatural or magical causes could be re-explained by natural causes. Through careful observation of the body, physicians began to understand that different organs and parts of the body performed distinct functions and that illness was the result of a breakdown of those functions.

Although natural causality predominates in the literate tradition of Chinese medicine, over the centuries supernatural and magical causes are everywhere present in the wider spectrum of healing practices in China. Even in the literate tradition, obvious examples of magical causality are easily spotted in the realm of medicinals, as is the case of male animal genitalia consumed to enhance sexual prowess. In some cases, such as that of guī bǎn (Magical Correspondence

. Noteworthy here is the idea that magical causality lay at the origin of the yīn-yáng and the five-phase systems of correspondence, where, in their original conception, members of each category were presumed capable of influencing each other.

Analysis and Analogy: Complementary Approaches

Chinese medicine is often contrasted with biomedicine regarding the focus of its attention. Biomedicine and the sciences on which it is based view any thing or phenomenon in terms of its constituents and things with which it comes into contact, while Chinese medicine views any thing or phenomenon in terms of its relationship to, resonance with, or similarity to other things in the world. The two approaches have often been labeled as microscopic

versus macroscopic

respectively. We prefer the terms analytical

and analogical

because the former approach does not necessarily entail the use of microscopes or lack of concern for the bigger picture.

Contrasting characterizations of this kind are acceptable provided they are understood to be relative. Both the analytical and analogical approaches are applied in both Chinese medicine and Western medicine. The difference lies in the degree to which and the purpose for which each is used, as we will discuss over the following pages. In biomedicine and the sciences in general, evidence of the analogical tendency, though relatively scant, is not negligible. In Chinese medicine, by contrast, the analogical approach is far more prominent, although the analytical tendency is just as clearly in evidence.

Analytical reasoning rests on a belief in natural causality. Analogical reasoning in Chinese medicine, which manifests in many ways, is partly rooted in magical causality.

The Analytical Approach

The analytical approach is one by which any given object or phenomenon is understood in terms of its constituents and things with which it comes into contact. We can isolate three elements within this approach:

- Materialism, the belief that all phenomena can be explained in terms of matter perceived by the senses.

- Mechanism, the notion that all phenomena are attributable to physical causes, that is, they can be explained in terms of natural laws (as now by the laws of physics and chemistry).

- Reductionism, the theory that any complex thing or phenomenon can be understood by breaking it down into the simplest components or processes.

Expressed in this way, the analytical approach, which appears as a complex product of a sophisticated intellect, is more properly seen as being integral to all problem-solving and technological innovation in human history. It was a necessary element in the development of hunting skills, clothing, mastery of fire, and tool creation. It is not even confined to humans, since it is found in many mammals, certain birds (notably crows), and even invertebrates (notably octopuses).

Though many regard materialism, reductionism, and mechanism as antithetical to Chinese medicine, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that this is not the case. Materialism and mechanism are reflected in explanations of health and sickness in terms of the interactions of material things, rather than supernatural powers. Reductionist thinking is reflected in the notion that the body is composed of distinct organs, which each perform specific functions.

Numerous clues as to how our bodies work can be gained from correlations between, and inferences from, facts directly observed with the unaided senses. These include the internal architecture of the body as revealed through rudimentary dissection (of human beings or animals) and subjective sensations from within the body, signs of wellbeing and illness, responses to environmental influences (including weather and food), lifestyle, and psychological stimuli. We can be confident that this cognitive process was the starting point for a rational understanding of health and sickness, as much in the East as in the West, as the following examples show.

- As to digestion, subjective experience tells us ingested food collects in a place below the lungs and is passed down through the trunk to the anus. Rudimentary dissection would have revealed the various distinct parts: esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Since food is necessary for survival, it follows that these organs extract substances from food that our bodies need. Many commonly experienced discomforts such as diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain and fullness, belching and flatulence correlate highly with dietary irregularities. Therefore, the smooth passage of food through and out of the alimentary canal can also easily be understood to depend on the health of the digestive organs.

- As to breathing, subjective experience tells us that air goes in and out of our chests as we breathe. Dissection would have revealed the lung as a spongy organ capable of holding air. Since we need to keep breathing to survive, it follows that air, or something contained in it, is necessary for the body to work. Breathing difficulties can easily be understood to reflect a problem with the lung.

- As to urine, subjective experience tells us that urine is stored in a place just above the pubic bone. Dissection would have enabled medical scholars to trace its source to the kidney. The connection between edema and reduced volumes of urine would have offered hints about the movement of fluids in the body.

- As to the heart, subjective experience tells us that there is a constant ticking in the chest, which turns into pronounced throbbing during physical exertion and emotional excitement. Dissection would have revealed the heart and its connections to the vascular system. The changes in heart rate produced by different emotions would certainly have been one factor that led to the Chinese medical notion that the heart stores the spirit and the Western conception of the heart as the seat of the emotions.

- As to the liver, we are not aware of this organ, because it does not move like the lung and heart do and lacks nerves that allow us to feel it. Dissection would have revealed a large organ in that position that is highly infused with blood. Hence the notion that the liver is intimately related to the blood, which was posited not only by Chinese medical scholars but also by their early Western counterparts.

- Emotions are related to our state of health. Each is associated with unique sensations within the body, often in different locations. It is not surprising, therefore, that they might each be associated with internal organs, as they are in Chinese medicine.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1321664111">[1]

- As to interaction with the environment, we all instinctively know that extreme cold or heat can threaten life; hence the invention of clothing and shelters. Severe dry or wet conditions may not only affect our food and water supplies but may also directly cause abnormal physical conditions. Exposure to various elements can cause fever, aversion to cold, and sweating. Combinations of environmental conditions produce special effects. Wind exacerbates the effect of cold on the body, while humidity can exacerbate the effects of heat. Combined conditions of this kind are easily correlated with specific pathologies, such as cold and dampness with joint pain (arthritis).

Conclusions from such observations do not necessarily require much conscious reasoning since they are grounded in the day-to-day experience of our unaided senses. Whether such conclusions are reached intuitively or intellectually, they clearly reflect a materialist, mechanistic, and reductionist understanding. Not surprisingly, therefore, the digestive function of the stomach and intestines, the respiratory function of the lungs, and the urinary function of the kidneys and bladder as conceived of in Chinese medicine are consistent with the modern biomedical understanding.

It is important to understand that the purview of early Chinese medical scholars was confined to direct naked-sense observations. In their anatomical studies, they never sought to investigate the internal structures of the body parts and organs that they found. Their initial realization that parts of the whole functionally contributed to the maintenance of the whole did not prompt the intuition that the parts of each part might functionally contribute to the whole of the part. Because they only saw gross organs, it was natural to expect that each of them would have a limited number of functions.

The Analogical Approach

Without the aid of technology, the analytic approach only went so far in helping early Chinese medical scholars to understand health and sickness. Instead of pursuing the analytical approach further, they sought to understand the body and disease processes by drawing comparisons with phenomena outside the body. We refer to this latter approach as the analogical approach,

in contrast to the analytical approach, characteristic of the pure materialist, mechanistic, and reductionist principles more exclusively applied in biomedicine. Analogy is the act of understanding or explaining a thing or phenomenon by comparison with another.

Analogy is the underlying component of the main paradigms of Chinese medical thought that are mostly the product of analogical reasoning. These basic explanatory frameworks, discussed in further detail in paradigms, are as follows:

- Magical correspondence, which rests on the belief that similar things influence each other.

- The qì paradigm, the theory that the body, just as the whole universe, is made of a single substance qì, understood by analogy to mist and clouds, and that all activity can be explained by a diffuse, active form of it.

- Systematic correspondence, observed in yīn-yáng and five-phase theory, represents the notion that numerous phenomena can be categorized according to binary or quinary classes on the basis of causal and analogical associations.

- The empire paradigm, which uses the imagery of a country, its geography, its economy, and its government to describe the body.

Chinese medicine’s great reliance on analogy accounts for the difference between its theories and those of modern medicine. It enables us to understand how organs acquired functions inconsistent with those described by biomedicine. It also explains how the viscera were each deemed to govern a body constituent (sinews, vessels, flesh, skin and body hair, and bones), to open at a specific body orifice (eyes, tongue, mouth, nose, and ears), to be associated with one of the five minds (anger, joy, thought, worry, and fear) and one of the five voices (shouting, laughing, singing, wailing, and groaning), and much more.

Explaining all the different analogies is a complex issue. Analogies vary greatly in their cognitive significance, from explanatory metaphors to almost magical cosmological resonances. They are drawn from a multitude of sources. Some analogies that would have been obvious to people in the formative period of Chinese medicine are less clear to us. Many Chinese medical theories are the result of a combination of analysis and analogy or a complex mixture of multiple analogies.

Popular Western Views

Many Western adherents of Chinese medicine believe that materialism, mechanism, and reductionism are characteristics of modern Western biomedicine and that they are absent in Chinese medicine. The evidence suggests, on the contrary, that early Chinese physicians explained organ functions in mechanistic terms as far as their direct observations permitted, and that they applied analogy to gain a more detailed understanding.

Although Westerners familiar with Chinese medicine know about qì and the yīn-yáng and five-phase theories of correspondence, they are less aware that analogy is common to all these constructs and so much more of the theoretical content of Chinese medicine.

Scope and Significance of Analogy

Chinese medicine as we now know it started to take shape as a set of healing and health-maintaining practices based on theories of physiology and pathology at a time when none of the tools of investigation we now have existed. Medical scholars instead developed their knowledge of the body by comparing the little they could see with things outside the body that they understood better. This cognitive process is calledanalogy,signs of which are ubiquitous in Chinese medicine.

Analogy is a cognitive process underlying metaphor, simile, allegory, metonymy, and symbolism. It is the use of a familiar thing, the source, to name, represent, describe, or explain a less familiar thing, the target. So, for example, when we use the metaphorical term mouse

in the context of computers, we are applying an analogy in which the furry rodent is the source and the computer device is the target.

In science, analogy was once regarded only as a didactic or explanatory device, and of no use in establishing sound theories. In literature, metaphor and allegory were regarded as esthetic literary devices. However, over recent decades, neuroscientists and linguists have found solid evidence to show that analogy, often referred to as metaphor,

is essential to our understanding of the world.

The cognitive linguist George Lakoff has shown that many of our ways of expressing complex and abstract phenomena derive from our basic human need to navigate three-dimensional space. Time, for example, is expressed through spatial metaphors. Developments in time are expressed as journeys. The mind is expressed in so-called container metaphors, and communication is expressed in terms of conduit metaphors.

Metaphor, or analogy, is not just a question of linguistic expression. We often talk about quantity in terms of a vertical scale. For example, we express an increase in quantity as rising

and decrease in terms of falling,

dropping,

plummeting.

Neuroscientific research shows that when we are thinking and speaking of quantities in such metaphors, not only do the parts of the brain that deal with quantities become active, but also those that deal with the vertical dimension.

Synesthesia is a well-known phenomenon in which one sense reacts to the stimulation of another sense. For instance, some people have an anomaly whereby they see letters of the alphabet or musical notes as colors in their minds. Neurological research has shown that synesthesia is much more prevalent than once believed. People holding a hot drink in their hands or sitting in a soft chair are more likely to react favorably to an interlocutor than those holding a cold beverage or sitting on a hard chair. One famous experiment devised by Wolfgang Köhler in the 1920s is the Kiki Booba experiment, in which speakers of different languages are asked which of two abstract visual shapes they would call Kiki and which they would call Booba. Over 90% of respondents choose Kiki for the jagged, spiky shape and Booba for the rounded, ameba-like shape. The findings are interpreted to indicate analogousness between the voiced and unvoiced consonants and rounded and unrounded vowels on the one hand and visual shapes on the other.

|

| Which would you call Kiki, and which Booba? |

|---|

Analogy is built into evolution. When the human mind came to be concerned with moral issues, the concept of moral displeasure came to be registered in brain regions that produce a feeling of disgust in response to foul-tasting foods. Similarly, emotional depression is felt in pain centers of the brain, even though the condition is not characterized by physical pain.

To return to Lakoff, he believes that metaphor explains many of our complex concepts, such as political ideologies. He traces conservative and liberal ideologies to conceptions of the family. Conservative ideas, he says, are based on the family ruled by a strict, protective father who imposes discipline and prepares children for competition, while liberal ideologies are based on the family ruled by nurturing parents who encourage openness to others and new ideas. These metaphors allow us to understand why seemingly disparate ideas cluster around the concepts of conservativism and liberalism.

Furthermore, the mind is capable of understanding a single thing in terms of more than one analogy. Conservative-liberal politics has been shown to reflect analogies not only to the family, but also to biological disgust for inedible foods and filthy environments. Conservatives tend to be more prone to disgust, hence their beliefs in moral purity, religious sanctity, familial traditions, and clear national borders that keep unwanted migrants out. Liberals, by contrast, are more open to new ideas and cultural diversity. Levels of biological disgust among individuals is a significant predictor of election voting tendencies. The disgust metaphor combined with parental metaphors helps us understand the connections between ideas that cluster around conservatism and liberalism. When we come to discuss analogy in Chinese medicine, we will find many examples of such mixed analogies.

Modern biomedicine often uses metaphor to name and explain things. When early anatomists wanted a word to name the bony structure that forms the base of the abdominal cavity, they chose the Latin word pelvis, meaning a basin,

by similarity of shape. When seeking terms to denote the three tiny bones of the ears used in capturing sound, they named two of them malleus and incus

(hammer

and anvil

) by the similarity of their form and mutual functional relationship. Pathological phenomena characterized by redness, swelling, heat, and pain were called inflammation.

White blood cells that destroy pathogens by engulfing and digesting them were named macrophages

(literally, big eaters

).

In a broader and deeper sense, analogy has guided efforts to understand the world by providing hypotheses about the way things work. The brain is a classic example. Although much is now known about how the brain works, much is still unknown, such as what form memories are stored in and how consciousness arises. Neuroscientific research has been influenced over recent decades by the idea that the brain must in some ways work like a computer, so that, for example, neurons are viewed as being like a circuit board and memories as being like computer files that can be opened up for view, put away when not in use, and even edited. Neuroscientists use analogies from experience in creating artificial intelligence to create hypotheses that can be tested. In other words, analogies of a prospective nature are applied to the target in the hope of revealing truths about it.

The ideas of Lakoff and others have influenced Chinese medical scholarship. As a result, discussion of analogy, once avoided for fear of making Chinese medicine appear unscientific, has now gained in acceptability. Chinese medical scholars, such as Jiǎ Chūnhuá (

In early China, where anatomical investigation was very rudimentary, and biochemistry was beyond imagination, analogy was a major tool applied in the effort to fathom the secrets of the human body and mind and to understand health and sickness. Early medical scholars used prospective analogies to test ideas about how the body worked. In short, analogy was not merely a method of naming or describing something but also a tool for investigation.

Despite the importance of analogy as a cognitive device for understanding phenomena in Chinese medicine, Western students may be less aware of it than Chinese students, since much of the metaphor characterizing its expression is deleted in translation. Still, enough terminology is literally translated for Westerners to be aware of the abundance of overt metaphor in all aspects of Chinese medicine: the engendering cycle,

mother and child,

triple burner,

florid canopy

(the lung), stringlike pulse,

head heavy as if swathed,

qì stagnation,

broken metal failing to sound

(hoarse voice from lung vacuity), heaven-penetrating cooling method,

water qì intimidating the heart,

Peaceful Palace Bovine Bezoar Pill.

Not so widely appreciated is the fact that deeper cognitive analogies underlie the description of many functions of the internal organs, the association of body parts, orifices, and emotions to the five viscera, the concept of qì and the channels, the understanding of the six excesses (wind, cold, summerheat, dampness, dryness, and fire) as causes of disease, and the formulation of therapeutic modalities. The importance of analogy derives in large part from the fact that qì, yīn-yáng and the five phases, so widely applied in Chinese medicine, all have roots in analogy. However, many people are unaware that analogy is the underlying principle of these theories.

Close scrutiny of Chinese medical theory reveals the imprint of analogical thinking in almost every aspect. Early medical scholars were highly attuned to the recurrent patterns among the countless phenomena of the natural world and the inner workings of the body. These observations enabled them to erect theories about the way the body worked and how it interacted with its surroundings. Though many of the functions and pathological processes identified in this way bear no resemblance to those of modern scientific medicine, they were nevertheless subjected to clinical testing insofar as disturbances could be reliably corrected by the therapeutic modalities available. It is noteworthy that whereas therapeutic interventions have undergone considerable change and refinement over the centuries, the core theories of physiology and pathology have barely changed. Though this certainly reflects a Confucian reverence for the early authorities, it also attests to the usefulness of the original theories and the skill of later clinicians.

The importance of analogy is recognized in the Nèi Jīng, since the Sù Wèn (Chapter 76) states, Without drawing comparison of kinds [i.e., analogy], this cannot be clearly understood

(When heaven (i.e., the weather) is warm and the sun is bright, a person’s blood becomes fluid and his defense qì floats, so that blood flows easily and qì moves easily. When heaven is cold and the sun is yīn (i.e., dim), a person’s blood congeals and their defense qì sinks [to deep within the body]

(

The authors of the Nèi Jīng did not share their direct observations or explain their inferences. Although explicitly aware that they were using analogy, they did not explain how they arrived at each specific analogy they drew. Analogy is a complex phenomenon that straddles both natural causality and magical causality. It can reflect beliefs in natural causality, since things with similar attributes can be found to behave in similar ways. It can also reflect beliefs in magical causality, where similar or related things are presumed to have actual causal connections. So, it is not always clear which type of causality was operating. Analogy is based on known qualities of the target that are perceived as resembling known qualities of the source. A problem arising here is that no two things are ever exactly alike. Sometimes it is unclear what precise qualities of the source and target are intended. Furthermore, analogy can be based on qualities of the source that are not directly observable, but nevertheless expected in the target. Given all these possible variables, we can only offer plausible reasons to explain in detail how the Chinese medical model came into being.

Modern Chinese textbooks speak of the importance of analogy in their introductions. They include numerous quotations from the Nèi Jīng that contain examples of analogy. When modern Chinese medical scholars discuss the essential characteristics of Chinese medicine, the one most frequently mentioned is the unity of Heaven and Humankind

(Heaven

means Nature and the higher forces influencing the universe. The Unity of Heaven and Humankind

has two meanings. One is that Heaven and Humankind are mutually responsive (

Thus, the Unity of Heaven and Humankind is simply an esthetically pleasing way of referring to a cosmology based on analogical reasoning. It implies the importance of analogy without overstating it. In the modern world, where science reigns among intellectuals, analogy is not valued because the scientific community regards it as a useless basis for constructing theories and at best only an inspiration for hypotheses. The importance of analogy is rarely mentioned in PRC English-language literature on which so much of the Western literature is modeled, because it goes against the authors’ evident purpose of convincing the international medical community of the value of Chinese medicine.

Despite the general recognition of analogy in the academic community, Chinese-language textbooks for students of Chinese medicine are careful to avoid a comprehensive discussion of analogy out of fear that it might invite unwanted scrutiny into the origin of Chinese medical theory. In the pages that follow, we cast aside such fears and take an unbiased look at some of the basic theories to see how analogy most likely influenced their formation. We say most likely

because how the ancients arrived at specific conclusions can only be a matter of informed conjecture.

Cognitive Significance of Analogy

Analogy may simply provide a name for a newly recognized object or phenomenon, offer a useful explanation of it, or even suggest ideas about how to understand it. Thus, different types of analogy reflect different degrees of cognitive significance.

Formal analogy is naming or describing an unfamiliar target object by means of the external characteristics, such as shape, size, or color, of a familiar source object. The term mouse in the context of computers is a perfect example. The similarity with the rodent is fortuitous and of little use for a deeper understanding of the computer device. In Chinese medicine, head heavy as if swathed,

sleeping silkworms below the eyes

(puffy swelling of lower eyelids), and eggplant disease

(an old term for prolapse of the uterus) all fall into this category. These are all simple linguistic metaphors chosen for want of better words or possibly for esthetic reasons. Formal metaphors stand in stark contrast to the types of metaphor described below, which are of greater cognitive significance in that they are of greater help in understanding the target.

Functional analogy is the naming, description, or explanation of a target in terms of the function of a familiar source. A menu as a list of functions on a computer display from which the user can select and activate the one desired is an example of this type. Falling within this category are the natural analogies of qì stagnation (qì is the commander of the blood,

and the mechanical analogy of raking firewood from under the cauldron.

Relational or systematic analogies are functional analogies used to name or describe related items. Biomedicine provides the example of the malleus (hammer) and incus (anvil), which describes the functional relationship between the two ossicles. Similar examples from Chinese medicine are the natural analogies of mother and child

(describing organs related by the engendering cycle), the groups of acupuncture points called well, brook, stream, river, and uniting or sea points

(Office of Sovereign

(the heart), Office of the Granaries (the spleen),

Office of General

(the liver), Office of Minister-Mentor

(the lung), Office of Forceful Action

(the kidney), and the military analogies of defense

and provisioning

(AKA construction

).

Pervasive analogy is analogy used to name, describe, or explain a broad domain of multiple targets by means of a domain of multiple sources. In Chinese medicine, waterways and transportation metaphors are often used to describe qì and the channel system: qì stagnation, qì counterflow, and point names such as Pool at the Bend (

Magical correspondence analogy supposes that a similarity between target and source reflects an ontological identity or causal relationship. Typical examples that are still to be seen in Chinese medicine are the correspondences between the physical nature and the actions of medicinals, such as tiger bones having the action of strengthening human bones. The correspondence between wood and the liver based on the similarity in size and color of the organ to a tree trunk also fits into this category.

Systematic correspondence analogy: The yīn-yáng and five-phase doctrines have the philosophical aim of making sense of the world by understanding it as being reducible to a limited set of principles observed in similarities between many of its parts. They involve formal and functional analogies between sets of two target objects to the two yīn-yáng sources or sets of five targets to the five-phase sources. They impose strict requirements on analogy in that there must be a full complement of two or five targets that each bear similarities to the sources and relate to each other as the sources do.

Prospective analogy is the analogy between a well-understood source to a poorly understood target with the expectation or assumption that the target will be similar to a source. In neuroscience, the analogy of the brain to a computer is a prospective analogy that offers testable hypotheses. Here, the prospective analogy involves expectations to be tested.

In Chinese medicine, prospective analogies are seen particularly in yīn-yáng and five-phase correspondences. The notion of storage (

Sources of Analogy

Analogies in Chinese medicine involve the mapping of targets onto various sources from the realms of nature, transportation, government, the military, and mechanics. To give an idea of the broad spectrum of sources of analogy, we here provide examples.

Natural analogy: Nature with its myriad objects and phenomena is a major source of analogy and metaphor in any culture. Numerous instances are to be found in Chinese medicine. Very loose stool was at one time described as duck slop.

What we call bags

under the eyes are often described in Chinese medicine as sleeping silkworms

(like tempestuous billows wave crashing against the shore

(pearls rolling in a dish

(a knife lightly scraping bamboo

(sick silkworms eating mulberry leaves

(

Water metaphors are used to describe blood and qì. A major pathology of blood is blood stasis. The character for stasis is silting,

which the commonly used English translation stasis,

unfortunately, fails to reflect. Qì, as a substance that flows, is also described in water metaphors. It is susceptible to stagnation

(counterflow

(

The yīn-yáng and five-phase systems of correspondence employ numerous natural analogies, as will be discussed ahead.

Transportation analogy: These take roadways and waterways as their source, the latter overlapping with natural analogies. They are most prominent in the channel system. Examples: qì street (

Supernatural analogy: In the realm of acupuncture, and numerous acupuncture point names, many of which are no longer used, such as Ghost Gate (

Government analogy: The five viscera are given epithets of government offices: the heart holds the Office of Sovereign; the lung is his Minister-Mentor; the liver is the General; the spleen holds the Office of the Granaries; the kidney holds the Office of Forceful Action. The sovereign fire

is the yáng qì of the heart, while the ministerial fire

is that of other viscera. Medicinal therapy ascribes roles to individual agents in a formula that are labeled as sovereign, minister, assistant, and courier.

In the channel system, the governing vessel

and the controlling vessel

are named after ancient government positions. The bowels and viscera as said to govern

body constituents and functions.

Military analogy: The analogy of the body as an empire is also reflected in military analogy. The intrusion of external evils into the body and the body’s resistance to them are described in combat metaphors. The enemies of the body are called evils,

implying that they are subversive influences on a healthy nation. Evils are said to invade

(assail

(defense qì

(provisioning qì

(AKA construction qì, invades

the stomach or spleen.

Military analogy is also found in therapeutic terminology. A powerful treatment to remove a strong evil (pathogen) is called attack

(expelling

(repressing the liver

(

Inappropriate supplementation in patients with repletion is often described as shutting the gate and keeping the intruder inside

(detaining the evil

(departure of the robbers leaving the citadel empty

(

Military analogies have also been used to explain strategies underlying treatments. According to the Ling Shu (Chapter 55), in the art of war it is said, do not engage with [an enemy] who is hungry for battle; do not attack a well-arrayed army; in the art of needling, do not needle scorching heat or gushing sweat.

The famous Ming dynasty physician Xu Ling-Tai, in his Yī Xué Yuán Liú Lùn (Medicine from the Source

) includes one chapter entitled On Using Medicinals Like Using Troops

(

Mechanical analogy: Since the mechanical principle is seen by many as being a feature of scientific explanations of health and sickness, it may be somewhat surprising how prevalent mechanical analogies are in Chinese medicine.

The action of the kidney in steaming

or distilling

fluids rests on an analogy to the process of evaporation, precipitation, and downflow of water in the environment or steam rising from a heated pot. The notion of the triple burner probably derives from an analogy to some mechanical apparatus. It is classically described in terms of the decidedly mechanical metaphor of governing the ditches.

The lesser yáng (shào yáng) channel’s position between greater yáng (tài yáng) and yáng brightness (yáng míng) is described as the pivot

(qì dynamic

is qì mechanism.

Mechanical analogies are commonly seen in methods of treatment. Raking the firewood from beneath the cauldron

(Increasing water to free the [grounded] ship

(Tilting the pot and removing the lid

(opened,

the downbearing action of the lung can carry water downward to the bladder.

Mechanical analogies notably include the container and conduit analogies that are fundamental to the conception of the organs and channels.

Container analogy: A container is anything that has an inside and outside, is capable of holding something and possesses one or more openings to let things in or out, such as a box, a crate, a pot, a house or other building, a reservoir, or a geographic area. As Lakoff tells us, we use this idea to describe states of things or people. When we talk of someone as being filled with joy,

or having had a full life,

being in love

or in transit,

or coming out of recession

or out of a coma,

we are using the container metaphor. This is because words like in,

out,

full,

and empty

imply a container.

Container analogies are used to express several key concepts of Chinese medicine. The most prominent example is seen in the idea of two classes of internal organs. These are called storehouse

or treasure house

for precious items, and exchange house,

i.e., a place where goods, services, and money were exchanged or where official business was transacted, referring to many official agencies. It also specifically referred to collection depots for grain destined to be dispatched to other parts of the country. Since in Chinese medicine, the fǔ are described as organs that discharge matter rather than store it, we can see that the source of the metaphor was a grain collection and forwarding station, which we can refer to as a dispatch house.

(The term fǔ in other contexts refers to an official residence, as in the lumbus is the house of the spleen

).

In the human body, the storehouses

store internally produced things: the liver stores blood; the kidney stores essence; the spleen stores provisioning. They also store spiritual entities: the liver stores the ethereal soul; the heart stores the spirit; the spleen stores ideation; the lung stores the corporeal soul; the kidney stores mind/memory. The dispatch houses

temporarily hold substances to be discharged into other dispatch houses or out of the body, such as food shunted through the organs of the digestive tract and out of the anus and urine expelled from the bladder.

Numerous other containers are identified in the body, notably the essence chamber,

blood chamber,

sea of qì,

the palace

(referring to the pericardium), the house of the kidney

(the lumbus), the house of the marrow

(the bones), the house of bright essence

(the head). In the Shāng Hán Lún (On Cold Damage

), there is also the stomach domain,

which refers to the intestinal tract from the stomach downwards. The heart is often referred to as the abode of the spirit,

and manic agitation is described as the spirit failing to keep to its abode.

The whole body is viewed as a container, as is reflected in the terms vacuity,

and repletion.

Yīn and yáng are normally in balance, but when there is too much of one or the other due, for example, to invading evils, the condition is described as repletion. By contrast, when there is too little of one or the other owing to poor functioning of the bowels and viscera, the condition is described as vacuity. Thus, the conditions are described in terms of the body as a container overfilled with things it does not need or lacking in things necessary for adequate functioning.

Containers have openings. The sweat pores, sometimes called the ghost gates

(corporeal soul gate

(essence chamber

(essence gate

(orifice

(clear orifices

(orifices of the heart

(clouding of the orifices of the heart.

Conduit analogy: Another mechanical analogy is that of a conduit, which refers to any tube-like structure along which things can flow. In English, this analogy underlies our ways of talking about communication, as reflected in usages such as conveying ideas,

getting thoughts across,

transmitting information,

and getting through to people.

In Chinese medicine, the conduit analogy was applied prospectively in devising the channel and network vessel (the waterways

(

Mixed Analogies?

As previously mentioned, we are capable of understanding a given thing in terms of multiple analogies. Different analogies are often used to describe the same thing. This phenomenon is highly prevalent in Chinese medicine. The channel system reflects the flow analogies of qì, natural analogies of physical terrain, and transportation analogies. The bowels and viscera are described in terms of the natural analogies of the five phases, in the political analogies of government offices, in container analogies, and in some cases in mechanical analogies (notably, the distilling function of the kidney). Within five-phase imagery, the source of an analogy may be the thing itself (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water as we normally think of them) or any of their specific associations (such as the five seasons and their associated activities).

Death of Analogy?

When we cease to be aware of an analogy implied in a metaphorical expression, we say that the metaphor is dead,

that is, it is no longer a metaphor. When we talk about the face and hands of a clock, we hardly think of the words face

and hand

as being metaphors. The very term dead metaphor

is a metaphor itself, and not an accurate one, since metaphors do not die but rather simply cease to be recognized by us as such. Some of the deadest

of metaphors are those of words from foreign languages, as we see in English anatomical terminology: pelvis

(basin), acetabulum

(vinegar pot), ventricle

(little belly), malleus

(hammer), glans

(acorn), pineal gland

(pine cone acorn). These terms are all Latin metaphors that are completely dead for most English speakers since they are only associated with body parts. Yet strangely, even these can rise from the dead when we learn Latin. Metaphors are only ever, to use a better metaphor, dormant.

The dying of metaphor is a normal linguistic phenomenon. It happens in Chinese just as much as in English. Thus, Chinese students are barely aware that their word for disease-causing entities, evil.

A quirk of the Chinese linguistic sensitivity is that it sometimes highlights metaphorical usage to indicate new meanings of words. For example, illnesses characterized by atrophy of limbs are called

The same process occurred in the development of storehouses

and dispatch houses.

It is also seen in to silt,

by the replacement of the water radical

Such changes in the writing of characters have only occurred in a few cases. Many other metaphors and analogies have been partially obscured by changes in the social, political, religious, and cultural world of the Chinese (as in the case of

Analogy Lost In Transmission

Western students should be aware that much of the imagery in Chinese terminology has been lost in the process of translation and transmission. This is because translators understandably consider plain language more helpful, because many of the metaphors and analogies are ambiguous or have become obscured by linguistic and cultural change, and because the importance of the cognitive significance of analogy has not been sufficiently emphasized by teachers and scholars.

Xié evil,

is often translated as pathogen,

a word that simply means a disease-causing agent. Wei wei,

which is a meaningless sound for people who do not speak Chinese. Some people find evil

and defense

to be distasteful moral and military metaphors, out of keeping with a medicine perceived as being based on the natural harmony of yīn and yáng. Few translators use renderings of

Acupuncture points form a whole area of terminology where analogy has been lost through the adoption of alphanumeric codes. In Chinese, they all have fanciful names such as Spirit Gate and Union Valley, but Westerners usually refer to these as HT-7 or LI-4. Of course, codes help in the memorization of the relative positions on the channels and avoid the complex problem of devising translations that reflect all the meanings of each name. However, for Chinese students, the names also have advantages because they sometimes hint at important features of the points. For example, Spirit Gate, located on the heart channel, is used to treat disturbances of the spirit, as the name suggests.

Many English-language books on Chinese medicine do not mention the government analogies of the heart as sovereign, liver as army general, etc. Although knowledge of these analogies is not always necessary to learn and practice Chinese medicine, it is indispensable for students wishing to understand how the Chinese medical model arose.

Chinese medicine traditionally revered the medical scholars of antiquity and never tried to extricate itself completely from the ancient view. In translation, preserving the analogies of the past as faithfully as possible provides the maximum amount of information about Chinese medical culture in its historical perspective. However, the preservation of metaphor is not a major concern of all English-speaking teachers, students, and practitioners or all translators writing for them. Most Westerners engaged in Chinese medicine do not know enough Chinese to compare translated terms with the original terms and thus to exercise informed choices. Furthermore, because native English-speaking translators are few in number, Chinese translators have played an influential role in the transmission of information. Not being native English speakers, they tend to doubt the ability of Westerners to understand and appreciate metaphors and hence often opt for plain

English. Under the influence of the modernization policies of the PRC, they tend to use modern medical terms as substitutes for philologically accurate translations.

The translation approach used in this text tries to preserve as much metaphor as possible, since metaphor helps students to understand the cognitive origins of Chinese medicine. Only through an understanding of the cognitive origins of the subject will non-Chinese teachers avoid the tendency to explain Chinese medicine in terms of pre-conceived ideas from their own culture. Many translators avoid replicating the metaphors of Chinese medicine to make the subject appear more scientific. Many, for example, prefer the term pathogen

or pathogenic factor

to represent the traditional concept of evil

is a metaphor that is inappropriate in a medical context. However, when English speakers frequently see the term evil

in the Chinese medical context, they tend to become less aware of its metaphorical nature, just as Chinese students do. Metaphor is worth preserving because even when we almost forget it, we never do completely. This is valuable in preserving the historical dimension of the subject.

See paradigms; analogy vs. analysis.

Intuitive Approaches

Intuitive approaches to knowledge, usually shunned in the modern sciences beyond their ability to provide a point of departure for investigation, have generally been more highly valued in Chinese medicine.

Judging the Inside from the Outside

Judging the inside from the outside (

It could be argued that the inferences about the internal workings of the body by analogy to the outside world are one manifestation of judging the inside from the outside. One example of this would be the inference of the free coursing function of the liver from the correspondence of liver to wood, reflecting the notion that the liver spreads its qì like trees spread their branches. However, judging the inside from the outside,

as its synonym knowing the interior from the exterior

(

In diagnosis, most of the information required to make sense of a patient’s condition involves judging the inside from the outside. There are two different aspects to this. One is judging subjective sensations by objective signs, such as when we detect heat, cold, or pain by the posture and bearing of the patient or any abnormal movements they display. These inferences are based on our personal experience of similar conditions or on verbal reports by many patients evincing such objective signs. The other aspect involves correlating signs with our understanding of physiology. For example, cough, panting, and expectoration of phlegm allow lung problems to be identified. Abnormalities of the stool, patient’s reactions to cold, warmth, and pressure on the abdomen tell of spleen, stomach, and intestinal problems. Long voidings of clear urine and cold aching lumbus and knees enable a pattern of kidney yáng vacuity to be diagnosed. The tongue, pulse, and complexion are outward reflections of the state of all the bowels and viscera.

Of course, patients’ sensations, which we might describe as being internal, are important in diagnosis, but these must be externalized by the patients’ verbal expression.

Although judging the inside from the outside is often said to be a feature of Chinese medicine, the above examples suggest that it is nothing more than logical inference, formulated in the language of correspondence.

Inward Vision

Inward vision (the eye of knowledge

or the third eye.

All these concepts are visual metaphors representing a faculty that is clearly other than internal sensing (interoception) that tells of discomforts such as pain, hunger, and abdominal fullness, or physical sensations produced by emotions.

The celebrated Ming dynasty physician Lǐ Shí-Zhēn in his Qì Jīng Bā Mài Kǎo (Examination of the Extraordinary Vessels

) states, As to the tunnels in the inner environment [i.e., the channels and vessels], they can only be perceived by inward vision.

The channel and network vessel system does not correspond to any known biological entity and has not been isolated from the body. Some believe that inward vision may have played a role in charting the system. The concept of the life gate (

It is known that such practices as qì-gōng, breath control (

One example of this is the lung’s diffusion and depurative downbearing. Relaxed, slow abdominal breathing through the nose produces pleasant warm sensations that can be felt in the periphery of the body, especially on exhalation. This may be because carbon dioxide (CO₂), which is responsible for dilating vessels to allow greater absorption of oxygen into the blood, reaches higher levels of concentration than normal in the lung when breathing is less calm. The pleasant warm sensations, possibly attributable to better oxygenation and greater sensitivity in a relaxed mental state, might have been understood as lung qì diffusing outward to the exterior. Also, this kind of breathing also allows the practitioner to detect a sharp acrid smell in the nose, probably from nitric oxide (NO). Small amounts of nitric oxide produced by the body are added to the incoming air to enhance oxygen absorption and keep the nose clear. When breathing is shallow, the ratio of NO to air is higher than normal, so that it can be smelled. Acridity is associated with metal, and the smell of NO in the nose may have been one reason for assigning the lung to the metal phase. Furthermore, Chinese breathing practices often call for breath to be drawn in and down to the dan-tian (cinnabar field) in the lower abdomen. Although the descent of breath to the dan tian makes no sense to science, practitioners learn

to experience it subjectively. Since neuroscience has yet to fully understand the mechanisms of conscious control over the body, we reserve judgment about such things.

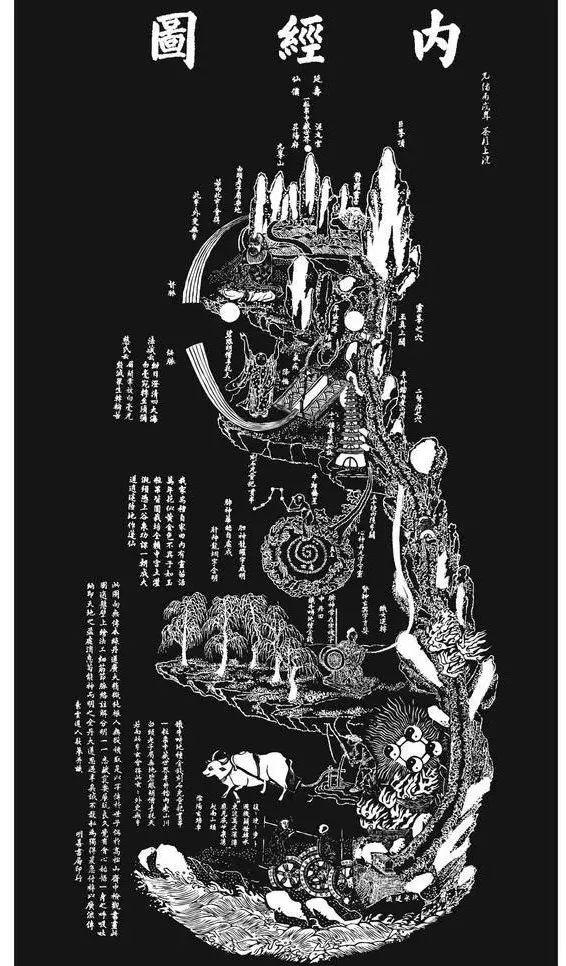

Inward vision is a complex issue. Neuroscientists now know that the raw data provided by our senses does not constitute an accurate representation of the world around us. To make sense of this data, our brains match it to our stored memories of experience. Hence, our perceptions are highly conditioned by our expectations, and expectations can be influenced by our experience, so much so that it is difficult to distinguish actual sensation from imagination. Hence, inner vision of channels, to return to the initial example, is likely to have been suggested by a prior charting of their pathways based on inspiration of a different origin. The famous Nèi Jīng Diagram (see image) presents the body in such concrete visual imagery that it is difficult to surmise what possible reliable sensory data could have inspired it. The only plausable explanation for such imagery is analogy.

|

| The Nèi Jīng Diagram |

|---|

Heart Knowledge

Heart knowledge

or heart approach

(life nurturing.

Sudden enlightenment

(light-bulb moment

also refers to this. It corresponds to the Christian notion of epiphany. In Chinese medicine, numerous book titles containing

Modern psychology distinguishes numerous kinds of knowledge. One is tacit knowledge.

This is knowledge that a person has but cannot express. A person with tacit knowledge has usually had that knowledge for so long that they cannot remember how they learned it or why it is true. They are simply aware that it is useful, accurate knowledge that exists in their mind. A specific form of tacit knowledge is practitioner knowledge.

An expert medical practitioner can see the core issues in a patient presenting numerous confusing symptoms and can apply an effective treatment. Intuitive insights, whether into an individual’s disorder or general processes of the body, have certainly always been credited by numerous physicians from any cultural tradition for their therapeutic successes.

Similar to the concept of tacit knowledge is nonconscious thinking.

Motorists are all familiar with the experience, sometimes called highway hypnosis,

of driving over a long distance without any conscious thought about the activity of driving. The act of driving is based, on the one hand, on tacit knowledge of how to drive the car and, on the other hand, on unconscious decisions that must constantly be made to keep the car moving along the route and to avoid danger. Nonconscious thinking occurs in many other of our daily experiences, such as when our minds create our first impression of a person.

Unconscious thinking may also produce new discoveries. According to conventional Western wisdom, the logical procedures of induction and deduction are believed sufficient to solve scientific problems. However, it is recognized in the philosophy of science that many discoveries are born through a light-bulb moment, as when Archimedes realized in his Eureka!

moment that the weight of a floating body is equal to the weight of the water displaced. Many other hypotheses may have similarly been born of sudden insights of the heart knowledge

kind arising spontaneously from constant preoccupation with certain kinds of problems.

Heart knowledge

in Chinese medicine refers to the medical insights arising from tacit practitioner knowledge. It is not unique to Chinese medicine or culture. It does not entail abandoning rigorous logical thinking or engaging in capricious fantasy. Rather, it is intuitive insight that comes with broad-ranging study and rich clinical experience.

One important thing to understand about all these related concepts is the central importance of the heart. The word for heart,

Pragmatism, Empiricism, and Trial and Error

In medicine, pragmatism is the notion that results are more important than theory or principles. Empiricism is the notion of basing treatments on experience. The trial-and-error strategy is conscious empiricism in the form of successive experiments to determine what treatments are effective. The three terms overlap in meaning in describing strategies that have their roots in natural causality and analytical reasoning.

Although analogy helped create the basic theories of Chinese medicine, it could not have done so without a belief in natural causality and the analytical knowledge of the organs and their functions it uncovered. Natural causality and analytical reasoning were also essential to the advancement of empiricism in evaluating treatments. Though in a modern light the basic theories of Chinese medicine may be seen to have many defects, these posed little impediment for the development of an empirically based healing system.

Acceptance of Early Theories

The Nèi Jīng, Nān Jīng, and Shāng Hán Lún, and Jīn Guī Yào Lüè were innovative and revolutionary texts that set the direction of the development of Chinese medicine for all future centuries. The Nèi Jīng andNàn Jīng represent accumulative efforts to offer a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain physiology, pathology, and therapy that was mainly based on acupuncture. The Shāng Hán Lùn and Jīn Guī Yào Lüè later incorporated that theoretical model into medicinal therapy.

Although Chinese medicine has constantly evolved since the appearance of these seminal texts, no major revolutions in basic physiopathological theory or the epistemology underlying it have ever occurred since the formative period. The combination of analytical reasoning and natural causality on the one hand and analogical reasoning with roots in magical causality on the other, welded by the principle of the Unity of Heaven and Humankind, was apparently so acceptable that the epistemological contradictions inherent in it went unnoticed. There is no evidence of outright refutation of the Nèi Jīng theories. With the Confucian reverence for elders and teachers, the seminal texts were considered authoritative for centuries and still are by many to this day.

The absence of epistemological concern reflects a strong pragmatic bent. By integrating numerous medical ideas and approaches of its time, the Nèi Jīng satisfied the practical need for an integrated model that explained both the internal workings of the body and the individual’s relationship to the environment and that provided the basis for interventions to prevent and treat illness. However, the pragmatism that accepted theories without question also encouraged the development of empiricism in clinical practice, which resulted in certain challenges to the theoretical model.

The Growth of Empirically Based Knowledge

The idea of empiricism in medicine is that a treatment is adopted if it proves to be effective. Conscious application of an empirical strategy implies deliberate experimentation and a trial-and-error approach. However, empirical treatments often have their origin in accidental discoveries.

We may presume that acupuncture and medicinal therapy were empirical and symptomatic in origin. Acupuncture most likely began with the empirical discovery that the stimulation of specific points on the body was found to help a certain condition and hence was deemed to be indicated for that condition. With experience, it was found that certain combinations of points could be stimulated to produce stronger effects. We can speculate that physicians began to develop the concept of a channel system when they had acquired knowledge of a sufficiently large number of points on the body to light upon the idea that they formed linear configurations.

Similarly, medicinal therapy began when certain plants or foods were discovered to have certain curative properties. When a person had a headache or a stomachache, a certain plant could provide relief. Some of these discoveries would have been accidental. Some would have been the result of the long-term observation that regular consumption of certain substances had curative or preventive effects. Others may have come about by deliberate trial-and-error experimentation.

The development of theories concerning the internal workings of the body and the causes of disease did not begin until the impetus for it was provided by notions of determinism that had developed in natural philosophy. Acupuncture was the first to develop theories concerning the functions of organs and how they could be disrupted. This movement gave rise to the Nèi Jīng and Nàn Jīng, which are theoretical works centering around the systems of correspondence, qì, and the channels and network vessels, with acupuncture as the main form of treatment. Zhāng Jī (Zhāng Zhòng-Jǐng) was the first physician to incorporate medicinal therapy into the theoretical structure of the Nèi Jīng. However, his ideas were not immediately adopted and took centuries to dominate mainstream practice. Thus, medicinal therapy was much slower to become theory-based and was more strongly influenced by philosophical and religious concerns.

Zhāng Jī’s Shāng Hán Lún is testimony to his strong empirical approach. We know that the use of formulas in the Shāng Hán Lún, with few exceptions (notably

Zhang evidently accepted the Nèi Jīng’s theories concerning physiology and pathology, because they are broadly reflected in his work. In the context of externally contracted disease, which he refers to as cold damage,

he accepted the notion that external evils, after entering the body, progressed through the channels one after another, giving rise to different symptoms at each stage. Yet, he rejected the Nèi Jīng idea that evils progress to a new channel each day, because he found in clinical practice that changes in presenting symptoms did not follow such a rigid pattern. Furthermore, the symptoms he gives for disease in each of the channels differ from those of the Nèi Jīng. Many scholars believe that the cold damage diseases discussed were not diseases of the channels themselves and that the channel names merely served as labels for stages of progression, even though Zhang himself never stated this. Thus, Zhang took from the Nèi Jīng the ideas he considered useful and developed them through his own clinical experience. He avoided criticizing Nèi Jīng ideas that he declined to adopt.

Nevertheless, evidence of conscious empiricism in much of the traditional literature is scant. The Běn Cǎo literature, for example, throughout the whole of its history, listed the effects of medicinals without reason or demonstration. Changes in actions and indications did occur over the centuries. These were attributable to new ideas and/or to clinical experimentation that the authors largely failed to describe. In the absence of clear justification for the ideas presented, it is often difficult to determine which factor was operant. The Confucian-influenced intellectual tradition encouraged reverence for canonized knowledge and discouraged outright criticism and accusation. Steely refutation of prior knowledge never became part of the medical scholar’s academic armamentarium, and hence neither did clear justification for new ideas.

We know that beliefs originating outside medicine affected the use of medicinals in early times. Between the Tang and the Song, for example, tortoise shells that had been used for divining purposes, known as bài guī (disclosing the mechanisms of heaven.

It is easy to see how the belief that tortoise shell increased intelligence was based on the notion that the shaman’s use of it in divining bestowed intelligence on a person who consumed it. It was only when Zhu Dan-Xi inaugurated the yīn-enriching school of thought that tortoise shell came to be used for the actions for which it is known today. Throughout history, only the plastron, the underside or yīn side of the shell was used, and it was not until the late 20th century, when chemical analysis revealed that the upper shell possessed the same constituents as the plastron, that the Chinese Pharmacopoeia changed the description to include the whole shell.

The move toward grounding treatments in empirical evidence was slow and sporadic. Though it is true that the Shén Nóng Běn Cǎo Jīng bears the strong influence of alchemists and contains much material that was more likely incorporated for religious and cosmological reasons rather than as a result of medicinal efficacy, we do know that at this time a body of highly empirical knowledge of medicinals was already developing and building on the results of medical experimentation in previous centuries. The amassment of clinical experience is evident in the formulary literature that developed from the Han period on. Both the theoretical and practical branches of medical literature show a clear progression of knowledge through the centuries, like the inclusion of Indian drugs and eye cataract surgery in Sun Si-Miao’s writings in the seventh century.

From the Song-Jin-Yuan period, new developments sprang increasingly from clinical experience with less consideration of the classics. The emergence of the Cold-Cool School,

Offensive Precipitation School,

Spleen-Stomach School,

and Yīn-Noruishing School

and later the development of the warm disease theory were all grounded in clinical reality. The impressive sophistication of physical examinations, notably the pulse and tongue examinations similarly developed out of clinical experience.

In sum, on the one hand, traditional Chinese medical writers perhaps failed to eliminate errors even when they recognized them. On the other hand, however, the literature provides ample evidence for their flexibility, experimentation, and creativity. Focusing more on medical efficacy than on the need to build a solid theoretical foundation allowed Chinese physicians to accept strategies that worked, even when the underlying mechanisms were not fully understood.

Empiricism Vs. Five-Phase Theory

The incorporation of the theoretical model into medicinal therapy was achieved at the expense of many elements of the model. In the acupuncture tradition of theNèi Jīng and Nàn Jīng, numerous complex theories were devised through mechanical application of the systems of correspondence, especially the various cycles of the five phases, engendering, restraining, overwhelming, and rebellion to explain the ways in which disease in one viscus can affect another viscus and to devise appropriate treatment strategies. Of all the numerous theories, very few were adopted in medicinal therapy, where empiricism held greater sway.

One example is the correspondence of complexion color in regions of the face to the condition of bowels and viscera. Originating in the Nèi Jīng, it is included in many larger modern diagnostic textbooks. However, whether these correspondences are regularly observed in clinical diagnosis is questionable. The same applies to the complex correspondences between the five minds

and morbid states of the viscera.

Another example is the complex use of the sets of five transport points below the elbow and knees on each of the twelve channels. The five points are the well, brook, stream, river, and uniting points each paired with the five phases wood, fire, earth, metal, and water respectively and hence also with the seasons of the year. They are each used to explain specific symptoms or illness occurring in specific seasons.

The complexity of such correspondence-based theories reached its apogee in the doctrine of the five periods and six qì, which Wáng Bīng added to the Nèi Jīng in the Tang period. This system calculates the weather patterns for each time of year and their effects on the human body. The six qì (summerheat, dampness, wind, heat, dryness, and cold) are related to the five periods (the five phases) by means of ten heavenly stems and twelve earthly branches as well as yīn and yáng. This doctrine appeared fully-fledged without any precedent in prior literature. It was never adopted into medicinal therapy, where more importance was attached to empiricism.

The use of these and other five-phase applications is still alive. Many modern practitioners consider them valid and effective. However, there are also many practitioners within the field and critics outside it who question the validity of complex correspondence-based theories of this kind, arguing that reverence for the classics and failure to develop empirical practices of validation prevented their refutation and that any apparent clinical successes achieved through their application are the result of chance, the placebo effect, or confirmation bias.

In medicinal therapy, the five-cycles have limited use. Modern basic theory textbooks, which emphasize theories applicable to medicinal therapy, point out that the five-phase cycles are used when they apply but are not used when they do not apply. Thus, for example, kidney yīn supports liver yin, reflecting the fact that water engenders wood. When a weakening of kidney yīn affects the liver, this is conventionally described as water failing to moisten wood

and the corresponding treatment is often described as enriching water to moisten wood.

However, cycle-based explanations are not applied to all relationships between the viscera. Illnesses involving two viscera corresponding to two consecutive phases cannot always be explained by the engendering cycle. Those involving viscera corresponding to next-but-one phases are not systematically explained in terms of the restraining cycle. Medicinal therapy pays lip-service to the founding doctrines but is not constrained by them.

After the theoretical model was incorporated into medicinal therapy, the five basic flavors (sour, bitter, sweet, acrid, and salty), associated with the five phases and thereby also with the five viscera and their related body parts, became fully integrated into pharmacological theory. The five flavors were said to each enter the channel associated with the phase-related organ: sour medicinals enter the liver channel; bitter medicinals enter the heart channel; sweet ones enter the spleen channel; acrid ones enter the lung channel; and salty ones enter the kidney channel. Nevertheless, the five-phase relationships are less important than other known actions associated with flavors: Sourness has an astringing action; bitterness dries and drains; sweetness supplements and relaxes tension; acridity disperses and moves; and saltiness softens hardness. A sixth flavor is blandness, which is associated with the action of disinhibiting water. These empirical observations carry much more weight than the five-phase associations.

The Difficulty Facing Trial And Error