Search in dictionary

Paradigms

理论典范 理論典範 lǐ lùn diǎn fàn 〔理論典範〕 lǐ lùn diǎn fàn

Chinese medicine’s fundamental doctrines concerning health and sickness have develop under the influence of analytical and analogical reasoning (see cognitive features). Analogical reasoning can be seen in four distinct theoretical frameworks, or paradigms.

Contents

- Magical correspondence

- The qì paradigm

- Systematic correspondence (yīn-yáng and the five phases)

- The empire paradigm

- The rain-cycle paradigm

Magical Correspondence

Analogy is closely associated with magical correspondence, which, resting on the previously mentioned principle of magical causality, is the notion that similar things form a single entity or share a special affinity and hence can influence each other. Only vestiges of magical correspondence survive in Chinese medicine today, but prior to the Nèi Jīng, magical correspondence often provided an explanation for diseases and a basis for their treatment. In pathology, a classic example of magical correspondence is a once-held belief that a baby is born with a harelip because its mother caught sight of a hare or rabbit during pregnancy.

In nutrition and pharmacy, magical correspondence is seen in the principle that physical characteristics suggest body parts to which they are therapeutically related. This idea is familiar to the West, where it is known as the doctrine of signatures. The Chinese have a popular expression supplementing a physical form [i.e., body part] with [the corresponding] form [of an animal or plant].

Pork liver and beef liver can supplement the liver and brighten the eyes. Tiger bone has bone-strengthening qualities. The penis of tigers, dogs, seals, and other powerful animals can enhance the male erection. Going a step further, anything edible that resembles a part of the body can enhance that part when consumed.

The principle is not limited to supplementation, since numerous medicinals with a wide variety of actions can be traced to it. A few examples follow.

- The use of ròu cōng rōng (Cistanches Herba, cistanche) to supplement kidney yáng in the treatment of impotence may have originally been inspired by its phallic appearance.

- The use of hé táo (Juglandis Semen, walnut) to supplement the kidney may originally have been inspired by the similarity of its appearance to the brain, which in Chinese medicine is the sea of marrow, closely related to the kidney.

- Guī bán (Testudinis Plastron, tortoise plastron) that had been used for divining purposes to fathom the secrets of heaven was long taken internally to enhance mental powers before healers determined that its actual action was supplementing yin. This is why, until recently, only the under (yīn) side of the shell was used (nowadays, the whole shell, called

龟甲 guī jiǎ, is used). - The human-shaped root called rēn shēn (Panax Ginseng, ginseng) can enhance the health of people that take it. The Chinese name literally means

man-wort.

- The use of yè míng shā (Vespertilionis Faeces, bat’s droppings), which in Chinese literally means

night bright sand,

to enhance vision was probably inspired by the glinting of insect eyes (actually wing fragments) in them. Although bats, which are nocturnal insectivores, are now known to be blind, their ability to fly without hazard in the dark may have suggested perfect night vision that was attributed, by magical correspondence, to the eyes of all the insects they had eaten, which caused the feces to sparkle. - Mù tóng (Akebiae Caulis, akebia) and tóng cǎo (Tetrapanacis Medulla, rice-paper plant pith) are both stems that can be described as hollow in the sense that they have numerous spaces running their full length. In other words, they are pipe-like stems that can conduct water. It may originally have been by analogy that physicians posited that when ingested these medicinals would enhance the conduction of fluids down and out of the bladder, in other words, that they possessed a diuretic property.

- Jiǔ cài zǐ (Allii Tuberosi Semen, garlic chive seed) supplements the liver and kidney, warms the lumbus and knees, invigorates yáng and secures essence, treating impotence, enuresis, and vaginal discharge. Jiu cai, the leaves and stems of the plant are a commonly eaten vegetable in China. Unlike other vegetables, garlic chives are harvested by cutting off the stems and leaves above the ground, leaving the roots to sprout again. Thus, they are understood to have a powerful root that can regenerate the whole plant. This quality may well have influenced their ascription to the kidney, which is the

root

of the body. In Chinese culture, the termgarlic chives

is often used cynically to meanthe people

as when repeatedly exploited by tyrannical rulers. - A disease mentioned in the Jīn Guī Yào Lüè (

Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Cabinet

) is百合病 bǎi hé bìng, often translated aslily bulb disease

because the main medicinal used to treat it is lily bulb (bǎi hé), which literally reads ashundred union,

a reference to the multiple layers of the bulb. Yet another plausible reason for the naming of the disease, which affects the heart and lung, lies in the lung’sassembling the hundred vessels.

For medical scholars who viewed the world through the prism of analogy, the similarity between both the lung’s function and the bulb would have been a highly significant resonance between macrocosm and microcosm.

In this context, we should not overlook obvious correspondences of the flavor, nature, and even color of medicinals to their action. The acrid flavor of bò hé (Menthae Herba, mint) and bīng piàn (Borneolum, borneol) are related to their dispersive, freeing, and opening action. The sensibly hot nature of gān jiāng (Zingiberis Rhizoma, dried ginger) is directly related to its interior-warming effect. Early use of red-colored medicinals such as chì sháo (Paeoniae Radix Rubra, red peony), mǔ dān pí (Moutan Cortex, moutan, and dān shēn (Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix, salvia) to act on the blood may have been suggested by a color correspondence. The sliminess of fresh shān yào (Dioscoreae Radix, dioscorea) may have suggested a connection with semen and essence. The burrowing activity of the earthworm, known medicinally as dì lóng or Pheretima, may have suggested it network-vessel-freeing action.

More commonly recognized is the pharmaceutical principle that light medicinals such as leaves and flowers tend to influence the upper and outer parts of the body, while heavy medicinals influence the deeper and lower regions. For example, guì zhī (Cinnamomi Ramulus, cinnamon twigs) and sāng yè (Mori Folium, mulberry leaf) resolve the exterior, while chén xiāng (Aquilariae Lignum Resinatum, aquilaria), a dense and heavy wood product, downbears qì. Be this as it may, exceptions to the rule are numerous. For example, niú bàng zǐ (Arctii Fructus, arctium), màn jīng zī (Viticis Fructus, vitex), and dān dòu chǐ (Sojae Semen Praeparatum, fermented soybean) are all seeds that act on the body and resolve the exterior. However, fruits and seeds develop where the flowers are, so in terms of position rather than weight, they are associated with upper and outer regions.

Pharmaceutical experimentation in China has certainly not been limited to magical correspondence. On the one hand, the therapeutic effects of medicinals originally suggested by magical correspondence have undergone confirmation or rejection through clinical practice. On the other, the actions of many medicinals have been identified simply through a process of trial and error, without the mediation of the doctrine of signatures. A feature of Chinese medicine is that the suggestions of magical correspondence have continually been subject to the test of clinical efficacy. In keeping with the general habit of Chinese medical knowledge creation, primitive and fallible elements, rather than being rejected, are worked into a fabric of knowledge in which clinical efficacy also plays a dominant role.

Lastly, and most importantly, magical correspondence predates the development of the Chinese doctrines of systematic correspondence and was instrumental in its development.

The Qì Paradigm

The Philosophical Concept

The word qì

denotes many things in Chinese medicine, not just the yáng qì of the body, which many Western students and practitioners almost exclusively associate with the term. It can refer to types of weather, the warming or cooling nature of medicinals, gas, breath, and even liquids and solids, having many uses in modern Chinese (see box on Uses of the Word

below). The concept of qì provided a framework facilitating the understanding of so many things in nature as well as in the body that we can refer to it as the Qì

in Contemporary Chineseqì paradigm.

Qì is a concept that natural philosophers derived by analogy and that was later adopted by medical scholars. The word originally denoted cloud, mist, or vapor. Philosophers, observing how water in the air could take on different forms varying from gaseous, liquid, to solid, came upon the idea that the entire universe was made of a single substance they called qì.

They distinguished between tangible/visible forms and intangible/invisible forms. Tangible forms were liquid or solid, while intangible types were air and steam or even more rarified substances that had no form. They believed that the more rarified kinds of qì could pervade and flow through matter. Mist and fog in the environment could seep into things and make them damp. Heat, cold, and dryness in the environment could penetrate things too. These were regarded as different forms, or more correctly, states of qì capable of penetrating matter.

Of course, modern physical explanations of these things differ. Cold, for those of us brought up with a scientific view of the world, is not a thing in itself but merely the absence of heat. Environmental dryness does not invade things but rather leaches out their water content. But for the Chinese, all these environmental influences were kinds of qì that pervaded things by analogy to the way in which dampness from water particles suspended in the air penetrate absorbent materials such as wood and cloth. See analogy vs. analysis: disease evils.

Qì In Medicine

Medical scholars applied the concept of qì to the body. They deemed that tangible forms comprise the solid and liquid components of the body (yīn qì), while intangible qì (yáng qì) was the force that powered activity in the body. The environmental influences, among them even wind, were considered to be types of qì capable of penetrating the body to cause various pathological conditions.

This conception had a great influence on the entire understanding of physiological and pathological processes, as well as the effects of treatment. The notion of an intangible substance

that had the power to flow through matter provided a way of explaining all physiological activity within the body and provided a causal link between phenomena occurring simultaneously in different parts of the body. Furthermore, things other than yáng qì were also attributed the ability to move through solid matter in the same way.

Uses of the WordQìin Contemporary Chinese |

|---|

Qì is a commonly used word in modern Chinese, referring largely to gaseous substances and abstract concepts. |

|

Gases

Other Phenomena

|

For 2,000 years, qì, as the animating force of the organism, provided a totally convincing explanation of phenomena observed with the naked senses. Withthe ability to penetrate and animate tangible matter, qì was considered sufficiently demonstrated by the clinical efficacy of treatments applied. However, qì, in its origin, is a speculative concept based on the analogy of cloud, mist, and vapor. Investigation using modern scientific methods has succeeded in isolating neither a single entity responding to the description of qì nor any physical substrate of the channels and network vessels along which qì is said to flow. To convince scientists of the clinical value of Chinese medicine, the clinical observations originally explained by qì must be re-explained in terms of objectively detectable phenomena.

Qì as Matter

Confusion for newcomers to Chinese medicine arises because in the English literature qì

is often exclusively used to refer to the yáng qì of the body. The main exceptions to this are the use of six qì

to refer to environmental influences and the four qì

to denote the thermonature of medicinals (cool, cold, warm, hot). In Chinese texts, by contrast, although qì

mostly refers to yáng qì, there are numerous instances of the term in other senses that make Chinese students aware of the wider meaning. Chinese texts often refer to the solids and liquids of the body as yīn qì.

They often refer to breath and breathing as qì (e.g.,

Qì is the basic stuff of the universe. It can assume different states ranging from solids, to liquids, and gases, and to the finest state of matter we call yáng qì, which has no form and is intangible. People who are brought up on modern physics easily assume that yáng qì corresponds to energy. This is confusing because the properties of different kinds of qì and the relationship between them are quite different from the properties of and relationships between matter and energy in physics. Although the use of the familiar term energy

as a translation of qì may bestow a veneer of scientific credibility on the Chinese concept, this requires that the word energy

be redefined–something that writers who use the term energy

do not normally do.

Only when we look more deeply into the concept of qì do we understand the properties of all states of qì and the relationships holding between them. This will become apparent in the ensuing discussion.

Yáng Qì Pervades Matter and Powers Activity

Yáng qì, having no form, can pervade solids and liquids. Being highly active, it animates the body and provides the motive force for all activity of and within the organism. It has the following functions:

Movement: Yáng qì moves constantly. Anything that moves in the body moves because of qì. The movement of food through the digestive tract, blood through the vessels, and fluids from one place to another is all powered by qì.

Retention: Qì holds substances and organs in their proper place. Pathological sweating, spontaneous bleeding, seminal loss, urinary incontinence, and miscarriage are often explained by the failure of qì’s retention function.

Transformation: Qì converts the air we breathe and the food we eat into the qì, blood, fluids, and solids of the body.

Warming: Yáng qì is yáng in nature and has the property of heat. Hence it warms the body.

Defense: Qì defends the body against invading external evils. When the body’s qì is strong, evils have difficulty entering. People with qì vacuity tend to catch colds.

Qì Explains Connections Between Body Parts

In physiology, qì provides the cause-effect link between phenomena occurring in different parts of the body.

Bowel and visceral qì: Each organ has its own qì, which powers not only the activity of the organ itself but can also flow to other parts of the body. In pathology, this allowed phenomena observed in certain parts of the body to be related to organs whose qì was understood to influence those parts.

One example is lung qì, which can move upward and outward to the exterior of the body, as well as downward. Since abnormal sweating and aversion to cold in the body’s exterior often occurs in tandem with cough and even panting, the ability of lung qì to reach the exterior explains why pathological phenomena occur in the exterior and lung at the same time (e.g., fever, aversion to cold, and cough). The ability of lung qì to move downward through the trunk, carrying water with it, explains how water swelling (edema) can occur with lung problems.

Another example is kidney qì, which is understood to draw lung qì downward, helping fill the lungs with air and promote the absorption of air into the body. This explains why an elderly patient with kidney vacuity signs also suffers from panting.

Channel qì: Qì circulates through numerous pathways in the body, called

No Need of Mechanical Explanations

The qì paradigm focused the attention of medical scholars on the overall movement and transformation of substances, with little interest in mechanistic explanations for their production, propulsion, and channeling. A vast variety of phenomena, which in biomedicine require highly complex mechanistic explanations, are in Chinese medicine simply explained by the single substance qì.

Food: All movement of substances within the body is driven by qì. Food moves through the digestive tract under the power of the qì of its various organs, chiefly stomach qì. Vomiting, hiccup, belching, and acid upwelling are explained as counterflow ascent of stomach qì.

The concept of qì thus obviated the need for mechanical explanation of the peristaltic action produced by the smooth muscle of the digestive tract.

Blood: Chinese medicine provides scant detail about how blood is produced. The Nèi Jīng makes contradictory statements as to where blood turns red. The blood is moved by the action of heart qì (or more precisely by ancestral qì, which gathers in the chest). There was no need for any explanation involving heart muscles, chambers of the heart, and the system of valves throughout the circulatory system. In fact, Chinese medical scholars never even charted the intricate system of blood vessels that can be found throughout the body by dissection. They were more interested in the flow of qì and its invisible pathways.

It should also be noted that Chinese medicine never developed anything comparable to the modern biomedical understanding of the bloodstream as the body’s main transportation system for physiological substances. Blood was simply understood as a fluid that provided nourishment to the body and that was produced and propelled by the action of qì. It was not accorded a general transportation function.

Fluids: Bodily fluids according to Chinese medicine are produced, distributed, and regulated by the action of the spleen, lung, kidney, and intestines. But how specific forms of fluid are created and move from place to place is not described in terms of any visible mechanical structures. No plumbing system is described. The production and movement of the various fluid substances of the body are attributed to the action of the qì of the bowels and viscera.

Phlegm: The literature tells us that the pathological fluid phlegm arises when stagnant water-damp concentrates as a result of spleen qì vacuity, for which reason it is said that the spleen is the source of phlegm formation. But since the qì of organs can act beyond their own confines, precisely where phlegm is produced and how it moves from the realm of the spleen into the lung is unclear. Other factors may be involved in phlegm formation, notably heat, which boils and thickens

water-damp into phlegm or qì stagnation that causes water-damp to accumulate and concentrate. Again, where these processes occur is not detailed.

Other Things Have the Properties of Yáng Qì

The notion that the whole universe is made of a single substance that assumes different but interconvertible forms allows things other than yáng qì to be invested with its properties so as to provide further explanatory possibilities.

Evils: Taking up the example of phlegm once again, two forms of this pathological substance are distinguished. A tangible form is phlegm in the lung that can be expectorated. An intangible form can move around the body and settle in the heart, causing clouded spirit (loss of consciousness) or in the flesh, giving rise to scrofula, goiter, and other conditions. Their attribution to phlegm rests on similarities to the tangible form seen in the tongue fur, the pulse, and symptoms of spleen qì vacuity, heat, or qì stagnation. Such a theory could barely have arisen without the notion associated with qì that matter can pervade matter. Other evils evince qì-like behavior. See analogy vs. analysis: disease evils.

Emotions: The qì paradigm provided a framework explaining how emotions and mental states (the five minds

and the seven affects

) could unleash pathological processes by affecting the movement of qì in specific ways: anger causes qì to rise; joy causes qì to slacken; thought causes qì to bind; sorrow causes qì to disperse; fear causes qì to descend; fright causes derangement of qì. Emotions are powerful forces that cause strong sensations in the body and can compel us to certain behaviors. Note here that our English word emotion

comes from the Latin emotio meaning stirring or agitation. It is therefore not surprising that the Chinese considered emotions as being akin to qì. Emotions and mental states are modulators of qì or even kinds of qì in the wider sense of the term.

Qì Flow in the Conception of Disease and Treatment

The broad conception of causes of disease can be summed up in the terms insufficiency

(vacuity) and superabundance

(repletion). Some conditions are caused by a lack of qì, blood, fluids, or essence. Others are caused by too high a concentration of immobile bodily substances (qì stagnation, blood stasis, fluid accumulations) or by the unwanted presence of evils of external or internal origin. Accordingly, treatment rests on two overarching principles: supplementation (

There are various kinds of supplementation and many different terms describing supplementing actions: enriching yīn (

- Moving qì (

行气 xíng qì), also calledrectifying qì

(理气 lǐ qì), is any action that makes qì move with the right force in the right direction. - Resolving the exterior (

解表 jiě biǎo) involves promotion of sweating to release evils from the body. - Clearing heat and draining fire (

清热泻火 qìng rè xiè huǒ) is eliminating heat by drawing it downward. - Disinhibiting dampness (

利湿 lì shī) involves leaching dampness out of the body by making it flow out with the urine. - Quickening the blood and transforming stasis (

活血化瘀 huó xuè huà yū) involves breaking up accumulations of inactive blood so that they can be dispersed in the bloodstream. - Freeing the stool (

通便 tōng biàn) means promoting the downward movement of fecal matter by enhancing the large intestine’s action of conveyance or by bringing more fluid into the digestive tract. - Ejection (

土法 tù fǎ) is the action of bringing up matter from the stomach to ease the digestive system or to remove phlegm-rheum in the upper body. - Opening the orifices (

开窍 kāi qiào) is the action of freeing the orifices of the heart to treat clouded spirit. - Dispersing food and abducting stagnation (

消食 xiāo shí) breaks down food in the digestive tract to restore normal flow.

The promotion of flow in various ways, not limited to the examples given above, is a principle that underlies a large range of therapeutic actions. It reflects the dynamic understanding of physiological and pathological processes embodied in general schemes of flow and stoppage fostered by the qì paradigm.

An interesting parallel is seen in changes in modern expectations about what health-care modalities, particularly in the alternative medical arena, can do for us. Until recently, people were mostly concerned with killing microorganisms on the one hand and getting enough nutrients that might be lacking in their diets. Withgrowing concern about toxins from the environment and decrease in nutrients in food, attention is now turning to freeing the channels through which cells take in nutrients and expel toxins. This includes the use of chelators and hyperthermic therapies to remove toxins, as well as the use of pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) and whole-body vibration to activate the body so that substances can move freely. It is as if we are shifting toward a greater emphasis on freeing the flow of substances within the body, similar to the Chinese medical concept of drainage.

How Viable Is the Concept of Qì?

Given that qì is a speculative concept that corresponds to numerous different functions in biomedicine, the question arises as to how treatment applied to the single substance qì could have the numerous desired effects on the body.

In medicinal therapy, all agents have indications for specific conditions. Those that act on qì either supplement or drain (promote movement). Each has indications for specific organs and conditions. According to pharmacology, each medicinal has numerous different chemical constituents having therapeutic effects that substantiate their traditional use.

The same is true of acupuncture. Needle stimulus at various points has been shown to produce neurobiological effects. It stimulates the secretion of called endorphins

to treat pain. It can stimulate changes in serotonin and dopamine to treat cravings. Other mechanisms have been identified, although scientific research is still far from explaining all the traditional effects of acupuncture.

Systematic Correspondence

Systematic correspondence is the principle shared by both the yīn-yáng and five-phase systems. The yīn-yáng doctrine classifies things or phenomena in sets of two, while the five-phases classifies things and phenomena in sets of five. In simple terms, the yīn-yáng system is a scheme in which cold is to heat as darkness is to light, as stillness is to activity, etc. The five phases are a system in which wood is to spring, green, sourness…, as fire is to summer, red, bitterness…, as earth is to late summer, yellow, and sweetness…, as metal is to autumn, white, and acridity…, as water is to winter, black, and saltiness….

The systems of correspondence are classification systems, in other words, they involve placing similar items in the same category and dissimilar items in different categories. Seeing similarities and distinctions between things helps people to understand them. Explaining to someone that a shaddock is something like a grapefruit or lemon, they immediately understand something about the essential nature of shaddocks, even if they have never seen or eaten one. Classification imposes order on the confusing welter of phenomena in our world. It is important in the modern sciences, typical examples being our botanical and zoological classification systems.

We can analyze correspondence systems in terms of categories, sets, and members.

- The categories are the two categories yīn and yáng and the five categories wood, fire, earth, metal, water.

- The sets are the pairs or groups of five things categorized in the systems. So, in the yīn-yáng doctrine cold and heat are one set, stillness and activity are another, etc. In the five phases, spring, summer, late summer, autumn, and winter form one set, while birth, growth, transformation, withdrawal, and storage form another.

- The members are the individual items, e.g., cold, heat; spring, summer, etc.

Systematic correspondence entails classification according to like qualities of the members of each set, but unlike the botanical or zoological classification systems, classification is also based on like relationships between members of each set. In the yīn-yáng and five-phase systems of correspondence, the number of categories is strictly limited, even though it includes vastly disparate objects and phenomena. The number of members in each set of either system must be the same. For any item to be incorporated into either system, it must fit into one category and have, in yīn-yáng, a corresponding item in the other category or, in the five phases, corresponding items in each of the other categories to which it relates in similar ways, so that both or all items become members of a full set. Thus, cold can be incorporated into the yīn-yáng system because it has a natural opposite, heat, with which it can form a cold/heat set.

Members of one set can influence each other in specific ways, reflecting a belief in natural causality. The similarities between all the sets reflect a world view in which consistency in relationships is seen throughout disparate phenomena that we call resonance.

This resonance has its origin in beliefs in magical causality (see

Yīn-yáng and the five phases provided great impetus to the development of Chinese medicine, not merely by providing an organizing framework for empirical data but also by offering clues about the functions of internal organs and explaining pathological processes for which no empirical data was available.

Yīn-Yáng

The terms yīn and yáng are words that originally denoted slopes on the surface of the earth that received greater or lesser amounts of sunlight. According to the classical Chinese description, yáng is mountain’s south [slope], river’s north [bank],

while yīn is mountain’s north [slope], river’s south [bank].

In other words, yáng slopes are those of the south faces of mountains and the north banks of rivers. Yīn slopes are those of the north faces of mountains and the south banks of rivers. This is because the south-facing, upward-facing and outward-facing planes, in general, receive large amounts of sunlight, while the north-facing, downward-facing, and inward-facing planes receive less.

Sunlight penetrates air but does not penetrate most solid objects except transparent things like glass. So, heavy, dense things like solids and liquids are yin, while diffuse, light things are yáng. The earth is therefore yin, while the space above the earth (

The sun provides light and warmth needed to sustain life. In general, the presence of light and warmth is associated with greater activity in nature than its absence. Therefore, activity and movement are yáng, while inertness and stillness are yin. This is nowhere more obvious than in the progress of the seasons. Spring and summer are a time of growing activity, while autumn and winter are a time of declining activity. Hence, early Chinese natural philosophers viewed spring and summer as the part of the year when yáng qì rises and yīn qì declines, and autumn and winter as the period in which yáng qì declines and yīn qì rises. A similar conception is seen in our English words spring

and fall.

In spring and summer, nature outwardly manifests in activity. In autumn and winter, nature draws into itself, becoming inert, latent, as it were, concealing itself. So, manifestation and concealment are also yīn-yáng qualities. In spring and summer, nature comes to life. In winter, many animals and plants die. And so, life and death are yīn-yáng pairs. The yáng world

(yīn world

(

In their origin, yīn and yáng were very much associated with divination and magical causality. The Yì Jīng (Book of Changes

) is a representative example that dates from the Zhōu Dynasty (hence the alternate name Zhōu Yì). The received text of the Yì Jing is composed of 64 hexagrams (

The yīn-yáng doctrine apparently did not need notions of magical causality to be perceived as being of value, since it also served as a system for organizing direct observations based on analogy within the confines of natural causality. The kernel elements of the system―dark/light, cold/heat, inactivity/activity, moistness/dryness, density/diffuseness―are all related by natural causality to some degree. The system’s application in Chinese medicine is largely confined to the realm of natural causality.

Three unique characteristics of the yīn-yáng system can be identified in its sources and targets.

- Targets must be paired: A yīn-yáng analogy can only be made between paired targets. It must be binary.

- Paired targets must evince similar relationships: Yīn and yáng are categories, not just of qualities, but also of relationship to a counterpart, so nothing can be described as yīn unless it has a corresponding yáng thing, without which it cannot exist. For example, up cannot exist without down, and cold cannot exist without heat. When one grows stronger, the other grows weaker. Furthermore, yīn and yáng things can in some cases be divided into yīn and yáng aspects. For example, movement is yáng, but it can be divided into upward movement, which is yáng within yáng, and downward movement, which is yīn within yáng. Heavy yīn things fall, while light yáng things float upward.

- Hierarchy of qualities: Yīn and yáng are composite sources of analogy based on the kernel concepts of darkness/light, cold/heat, inactivity/activity, moistness/dryness, density/diffuseness, and as new targets are associated with the yīn-yáng sources, they, too, can enter the pool of sources, potentially adding new qualities to yīn and yáng. However, since any target has multiple qualities, contradictions can arise. For instance, male is classed as yáng and female as yīn because men are stronger and more active, while women are weaker but more nurturing. It is true that men are generally heavier than women, which means that the sexes might be classified in the opposite fashion. Nevertheless, greater physical strength for strenuous activity trumps weight.

Yīn-yáng is applied in all realms of Chinese medicine from physiology to pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Unlike the doctrine’s application in the Yi Jing, its application in medicine appears to be largely constrained by natural causality, and notably limited to specific sets, namely cold/heat, inactivity/activity, down/up, in/out, moistness/dryness.

In physiology, internal organs are classified in pairs as yīn or yáng according to whether they store or discharge substances. As previously described, the storing organs (viscera) are called storehouses

for precious items. The discharging organs (bowels) are called dispatch house

for the collection and temporary storage of goods for wider distribution. This distinction is based on the in/out parameters of yīn-yáng.

The storing organs produce and store the internal substances of the body, notably, essence, qì, and blood, while the discharging organs in general pass on incoming substances such as food and outgoing substances such as stool and urine. This distinction enabled five organs to be designated as storing organs (liver, heart, spleen, lung, kidney), each paired with a discharging organ (gallbladder, small intestine, stomach, large intestine, bladder).

The yīn-yáng pairing, far from being a mere classification, facilitated conclusions about the functions of the organs. For example, the spleen, lying on the underside (yin side) of the stomach and assumed by its proximity to the stomach to have a related function, was understood as the organ that extracted nutrients from food in the digestive tract. The kidney, known to be connected by tubular structures to the bladder, which was clearly classifiable as a discharging organ (dispatch house

), was understood as the bladder’s corresponding storing organ (storehouse

). Since the existence of five storing organs further permitted mapping to the five phases, the spleen, as the producer of qì and blood, could be seen to share earth’s quality of engendering the myriad living things. The kidney, as an organ that stored essence,

responsible for reproduction, development, and aging, was found to possess the qualities of water and winter storage.

In pathology, yīn-yáng provides a broad scheme of classification applicable to any illness. It permitted a model based on the mutually opposing tendencies toward cold, inactivity, and moistness on the one hand and toward heat, activity, and dryness on the other. Although illness takes many different forms, it always involves some imbalance between fluids (yīn) and heat (yáng) in the body, arising either from insufficiency of fluids or yáng qì or from superabundance created by yīn excesses in the environment (cold, dampness) or yáng excesses (wind, summerheat, dryness, and fire). In this application, the body is considered as a container, in which yīn and yáng must stay in relative balance to maintain health. Insufficiency of yīn or yáng results in a relative emptiness of the container, called vacuity,

while superabundance leads to overfilling, repletion.

In pulse diagnosis, the yīn-yáng model helped physicians to detect numerous different pulse conditions. For example, sunken and floating pulses (down/up) indicate interior and exterior disease (in/out) respectively. A tight floating pulse indicates exterior cold. A rapid floating pulse indicates exterior heat.

In pharmacy, yīn and yáng provide a classification system for all medicinals: warm-hot and cool-cold. Warm-hot agents treat cold disease patterns, while cool-cold medicinals treat heat patterns.

The yīn-yáng paradigm interacts with the qì paradigm, which is based on the idea of flow or movement. The concept of qì as the original substance of the universe underwent initial development through the application of yīn-yáng, so that diffuse, invisible, but powerful forms of qì came to be understood as yáng qì, and dense forms as yīn qì. Hence, in medicine, these terms came to be widely applied to denote the motor force of all activity on the one hand and liquids and solids on the other.

Yīn and yáng are divisible, which means that a yīn or yáng phenomenon is potentially divisible into yīn and yáng. This notably applies to movement. Any movement within the body is understood in terms of yīn and yáng. Upward and outward movements are yáng, while downward and inward movement are yin. All activity is considered to be a balance of yīn and yáng movements of qì. Thus, closing/retention is yin, while opening/release is yáng. This is reflected in the understanding of sweating (the retention or release of sweat) and urinary conditions (retention or release of urine). This notion even applies to the spirit. When yīn and yáng are in balance, the heart spirit is strong but is contained

or held within

(bursts outward

(gathering

(accumulation

(

This combined yīn-yáng-qì conception of pathology is clearly reflected in the therapeutic actions of medicinals and the formulas. Yīn-blood and yáng-qì are supplemented where they are lacking. Excessive yáng heat is counteracted with cold agents; excessive cold with warm agents. Hyperactivity of yáng qì is counteracted with heavy settling agents. Evils in the exterior are driven out by increasing the flow of sweat by the use of warm acrid agents in the case of cold and of cool acrid agents in the case of heat. Internal dampness can be relieved by promoting urination. Qì stagnation is treated by promoting flow; blood stagnation is treated by quickening the blood and transforming stasis, i.e., by promoting blood flow and breaking up blood that is tending to clot. Almost every method of treatment is fundamentally understood in terms of restoring the yīn-yáng balance or by countering abnormal movements of qì and substances in the body.

Five Phases

The five phases (five materials

(

- Wood:

bending and straightening

(曲直 qū zhí) - Fire:

flaming upward

(上炎 shàng yán) - Earth:

sowing and reaping

(稼穑 jià sè) - Metal:

working of change

(从革 cóng gé) - Water:

moistening and descending

(润下 rùn xià)

The five-phase system operates in the same way as the yīn-yáng model, except that five targets, instead of just two, were required to form a set. Potentially any set of five things or phenomena possessing qualities like the above could be classed according to the five phases.

Among the things understood to be analogous to the five materials were the seasons of the year:

- Spring–wood;

- Summer–fire;

- Late summer–earth;

- Autumn–metal;

- Winter–water.

The addition of the seasons to the system greatly enriched the pool of analogy sources, so that each phase was not only associated with a material but also with the qualities of nature observed in each season. Thus,

- fire with growth and the intense activity of nature in summer;

- earth with the ripening of crops in late summer;

- metal with the purging of life brought by the first frosts of autumn;

- water with the stillness of winter when natural activity is minimal as animals remain in hibernation and plants survive only in root and seed forms.

In this way, birth,

growth,

transformation,

withdrawal,

and storage,

the essential characteristics of the seasons, came to be included as principal qualities of the five phases. From the seasons, corresponding times of the day and the position of the sun at each of them became associated with the five phases.

| The Five Phases in Nature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

| Season | Spring | Summer | Late summer | Autumn | Winter |

| Activity | Birth | Growth | Transformation | Withdrawal | Hiding/storage |

| Time | Sunrise | Midday | Afternoon | Sunset | Midnight |

| Position | East | South | Center | West | North |

| Weather | Wind | Summerheat | Dampness | Dryness | Cold |

| Color | Green-blue | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Flavor | Sour | Bitter | Sweeet | Acrid | Salty |

| Smell | Animal smell | Burnt smell | Fragrant | Fishy | Rotten |

| Animal | Chicken | Goat | Ox | Horse | Pig |

Just as in the yīn-yáng doctrine, qualities were not the only thing theoretically necessary for five-phase classification. There also had to be similar relationships between members of the sets of five, the most important of which are the so-called engendering

and restraining

cycles. In the engendering relationships, wood burns to produce fire, fire produces ash, which returned to earth (and nourishes arable land), earth produces metal ores, and metal causes water to condense. In the restraining relationships, wood restrains earth, fire melts metal, earth restrains water, and metal cuts wood. It was because of this vision that the five materials came to be known as five movements,

or five actions,

taking place in a cycle (hence the English phase,

meaning part of a cycle).

Things allotted to each of the phases evinced similar relationships: just as wood burns to produce fire, so spring gives way to summer; just as fire produces ashes (earth), so summer gives way to late summer; just as earth produces metal (ores), so late summer gives way to autumn; just as (cold) metal causes water to condense, so autumn gives way to winter. Just as water nourishes wood, so winter gives way to spring. The restraining cycle does not normally apply to the seasons, because the seasons are fixed.

The doctrine of the five phases developed later than the yīn-yáng system and was applied to medicine later too. A natural starting point for their incorporation into medical thought was the seasonality of disease. Many lines of the Nèi Jīng discuss diseases arising in one season and developing in the following season.

The five-phase system is naturally more limited in its application than yīn-yáng because instances of groups of five are much harder to find. Nevertheless, the powerful attraction of the five-phase system to early medical scholars is attested by the number of things in a physician’s purview are classified in groups of five:

- five viscera (liver, heart, spleen, lung, and kidney);

- five orifices (eyes, tongue [tip], mouth, nose, and ears);

- five body constituents (sinew, vessels, flesh, skin and body hair, and bone);

- five humors (tears, sweat, drool, snivel, and spittle);

- five spiritual entities (ethereal soul, spirit, ideation, corporeal soul, and mind/memory);

- five minds (anger, joy, thought, worry, and fear);

- five voices (shouting, laughing, singing, wailing, and groaning).

One interesting thing about these groupings is that whatever degree of actual physically observable cause-and-effect relationships inspired the connections between each viscus and its related body constituent, orifice, spiritual entity, and voice, the need for these to be incorporated into the universal five-phase structure was apparently of equal, if not greater importance to ancient medical scholars.

The number five clearly had a magical attraction since physicians suggested five-fold categories for many phenomena, even when each of the five has no correspondence with a phase, e.g., the five slownesses, the five stranguries, the five taxations, the five unmanlinesses, the five waters (these and many other terms beginning with five

can be found in this databse). However, this should be viewed against the background of general affection for numbers in the naming of groups of things: the two yin, three treasures/gems (essence, qì, and spirit), four rheums, six excesses, seven affects, eight principles, nine orifices, ten diffusing points.

Pharmacy also saw applications of the five phases: sour and green things enter the liver (wood); bitter and red things enter the heart (fire); yellow and sweet things enter the spleen (earth); white and acrid things enter the lung (metal); black and salty things enter the kidney (water). These examples suggest that magical correspondences are poorly separable from systematic correspondences. Although these principles do not work in every case, they would certainly have prompted investigation. The white color of jié gěng (Platycodonis Radix, platycodon), mài dōng (Ophiopogonis Radix, ophiopogon), and tiān dōng (Asparagi Radix, asparagus), which is associated with the lung in the five phases, may have suggested that these medicinals supplement the lung.

| Five Phases in the Body | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

| Viscus | Liver | Heart | Spleen | Lung | Kidney |

| Bowel | Gallbladder | Small intestine | Stomach | Large intestine | Bladder |

| Body Constituent | Sinew | Vessels | Flesh | Skin (and body hair) | Bone |

| Orifice | Eyes | Tongue | Mouth | Nose | Ears |

| Bloom | Nails | Face | Lips (and four whites) | Body hair | Hair of the head |

| Humor | Tears | Sweat | Drool | Snivel (nasal mucus) | Spittle |

| Spiritual entity | Ethereal soul | Spirit | Ideation | Corporeal soul | Mind |

| Mind | Anger | Joy | Thought | Worry | Fear |

| Voice | Shouting | Laughing | Singing | Wailing | Groaning |

| Government office | (Military) general | Sovereign | Office of granaries | Minister-Mentor | Office of forceful action |

| Aversion | Wind | Heat | Dampness | Cold | Dryness |

| Pulse | Stringlike | Surging | Moderate | Floating | Sunken |

Early Development of the Five Phases: The fact that each of the five phases represents multiple qualities allows considerable latitude in the matching of targets to sources. Because of this, the pairing of the viscera to the phases was somewhat arbitrary and in fact changed over time.

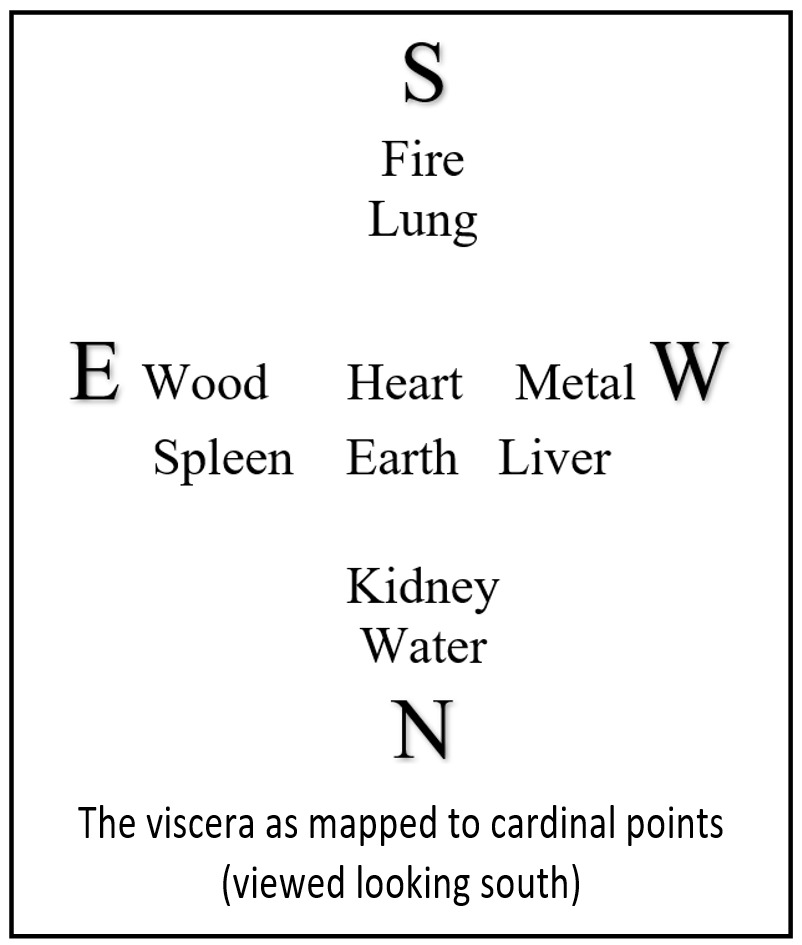

An early pairing of the viscera with the five phases was spleen-wood, lung-fire, heart-earth, liver-metal, kidney-north, which was determined by mapping the physical positions of the viscera in the body to the cardinal positions. In the daily cycle, the sun rises in the east (wood), ascends to the south (fire) where it reaches its highest point, and then descends toward the west (metal). So, in this earlier pairing, the mapping onto the viscera was based on the body facing southward, the left side corresponding to the east, and the right side corresponding to the west. Thus, the spleen, occupying the eastern position, was paired with wood. The lung, being the highest viscus in the body, was paired with the south and hence with fire. The heart below the lung in the center was paired with the central position and hence with earth. The liver, occupying the western position, was paired with metal. The kidney, the lowest or northernmost viscus, was assigned to water.

This configuration was apparently chosen because the rulers regularly made sacrifices in different parts of the country in different seasons according to five-phase associations. In spring, a sacrifice was made in the east, in summer in the south, in late summer in the central region, in autumn in the west, and in winter in the north. They believed that the sacrifices could influence the progress of the seasons, ensuring that the right weather came at the right time to create abundant harvests. Medical scholars would naturally have believed that this conception of the five viscera reflected a cosmic principle that maintained the health of the body just as it maintains the normal processes of nature through the diurnal and yearly cycles. We can hypothesize, therefore, that this pairing of the viscera to the phases was based on a belief in magical causality.

This older pairing of the viscera with the five phases was in time replaced by one based on correspondences of physical or functional characteristics of the viscera to five-phase qualities, namely the liver-wood, heart-fire, spleen-earth, lung-metal, and kidney-water correspondences that have consistently been used to this day. The switch from positions in the body to organ qualities was evidently prompted by knowledge of organ functions, notably inferred from direct observation of physical and functional characteristics, that is, by applying natural causality and the analytic approach to understanding how the body works. Thus, for example, the old configuration associated the heart with earth because of earth’s association with the central position, whereas the new configuration, instead, paired the spleen with earth on the basis that it was understood to extract nutrients to produce qì and blood (earth being the mother of all things). The old configuration paired the lung with fire, whereas the new configuration paired the heart with fire, presumably on the basis that a racing heart was associated with bodily heat produced by physical activity. In fact, the pairing of the spleen with earth and the heart with fire must have been pivotal in a shift toward the new configuration, given that the kidney’s association with water did not change and that directly observable functions of the liver and especially the lung provided little immediate basis for establishing their correspondence to wood and metal respectively.

|

| Reversed map with south at the top |

|---|

Theoretical Weaknesses

In its medical application, the yīn-yáng doctrine is mostly narrowly confined to down/up, in/out, cold/heat, stillness/movement; moistness/dryness. These sets of qualities are largely related by natural causality.

By contrast, the five-phase system exhibits a lesser degree of causal relationship. While the relationship between the seasons and the activities in nature (birth, growth, transformation, withdrawal, and storage) reflect natural causality, many other relationships do not necessarily (e.g., colors). The relationships between the phases and the viscera are based on the matching of purely incidental qualities (e.g., the matching of the liver to wood on the basis of its physical appearance). Furthermore, five-phase analogies are often based on different meanings of the phase names, notably whether a phase name is taken in a physical sense (as fire in the environment) or in an associated sense (fire as embodying the qualities of the season summer). Some analogies are forced and hard to explain, such as why the lung is associated with metal and why the small intestine is paired with the heart and associated with fire.

The Empire Paradigm

Just as the family provides a rich set of analogies shaping political values in the modern world, so the vast diversity of a country’s physical terrain and the human complexity of multiple communities engaged in different activities across that terrain provide rich sources of cognitively significant analogies. An abundance of metaphors from the domains of landscape, waterways, roadways, and national government suggests that early medical scholars thought of the body as being comparable to a country or empire as a geographic area and an economic and administrative entity. We call this the empire paradigm. The body thus viewed can be called the empire-body

or nation-body.

Paul U. Unschuld has pointed out that in their earliest formulation the pathways of qì and blood were understood to be entirely separate and that the notion that they were all interconnected to permit endless flow around the body coincided with the unification of China by the Qín Dynasty (221–207 BCE), which required that all the regions of a large unified country be closely interlinked by roads and waterways to facilitate the movement of goods and people.

The Chinese names of acupuncture points are metaphors from virtually every domain of the Chinese world of the time, but most prominent among them are topographical metaphors, waterway metaphors, and roadway metaphors: the Chinese words for mountain,

ravine,

cleft,

marsh,

sea,

pool,

hub,

and thoroughfare,

figure prominently in the nomenclature of acupuncture points. Even the Chinese word for acupuncture point, point.

Major pathologies such as qì stagnation (

The storehouses

and dispatch houses,

as the major organs were called, would have been of vital importance in an empire composed of interdependent economic regions.

Of special interest is a group of systematic metaphors describing the five viscera in terms of official government positions. The heart is the sovereign who rules with the help of a Minister-Mentor (chief minister and tutor to the sovereign), the lung. The liver is the army general. The spleen is responsible for the nation’s granaries. Finally, the kidney is in charge of forceful action. These metaphors, though not always mentioned in Chinese medical textbooks in Western languages, were nevertheless important in formulating the characteristics and functions of the organs (see analogy vs. analysis). They would have served as memes to capture the nature and functions of the organs. Most importantly, however, these analogies form a political hierarchy that reflects a distinctly Confucian worldview, which favored a strict social order.

Similarly termed officials

are the nose, eyes, lips, tongue, and ears, which are collectively known as the the five offices

facial features.

The idea of the organs as officials is reflected in the use of the terms governing

(governs

storage and governs

the bones. However, the metaphor is lost in translation when more familiar English terms are substituted. Impairment of functions is also described in terms of failure to perform the office of storage,

that is, impairment of the kidney’s storage function. It is an interesting coincidence that the word function

in English, which comes from Latin, originally referred to an activity associated with a public office and was only later used to denote an activity natural to a thing. However, that English metaphor is now dead

(dormant).

For the protection of the nation, the army is of especial importance. Thus, the body, conceived of as an empire, would have to have a strong defense force adequately provided with food and weapons, hence the paired metaphors defense

(provisioning

(wei

and ying.

The names of four government positions are used to describe four roles played by ingredients of a medicinal formula: sovereign, minister, assistant, and courier. Like the organ epithets described above, the designations of the four roles reflect a hierarchical structure of a country or empire.

It is an interesting quirk of the transmission of Chinese medical knowledge to the West that the empire paradigm has virtually disappeared from view in much of the influential literature because many transmitters consider the cultural roots of Chinese medicine to be unnecessary for its practice. Although Chinese medicine can be explained for clinical purposes without the empire-paradigm, it is impossible to explain how Chinese medical theories developed without reference to it.

The Rain-Cycle Paradigm

The rain-cycle paradigm is more limited in scope and significance than the previous four. However, it made a major contribution to the development of the bowels and viscera. It is most apparent in the theories concerning the lung's governance of the waterways. See analogy vs. analysis: lung, metal, Minister-Mentor.

Back to search result Previous Next